|

By Jim Hughes The print came into my possession quite fortuitously. In the photo magazine Camera 35, of all places, I had just published W. Eugene Smith's "Minamata" essay -- a devastating indictment of industrial greed and environmental genocide -- as photographed, designed and written by Gene himself, with the able collaboration of his wife Aileen. Shortly thereafter, I found myself spearheading a fund-raising/rescue mission to bring Gene home after he had lost most of his vision to the long-term effects of an earlier, appallingly vicious attack by company goons intent on preventing the famous American photographer from continuing to draw the world's attention to the unfortunate victims of mercury poisoning.

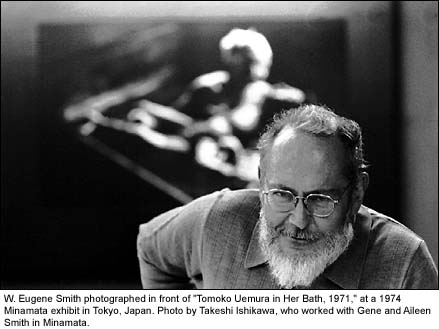

Thus it came to pass that for my 37th birthday I received, not a Bulova, but a large, 11x18 print of "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath" -- an original, the very print in fact that had been reproduced in the magazine, only a little the worse for wear and now signed in a dark area of the image with a black ballpoint pen (known in art circles as a "stylus") and matted and framed by Gene's long-time dealer, Lee Witkin (who, understandably, was not thrilled, I was told, at having "lost" a rare print he might have sold). A year after Gene's untimely death -- and after wrestling with my doubts for many months -- I finally came to the conclusion that I had no choice but to write his biography, a daunting responsibility whose true enormity I had in no way envisioned. Ultimately, the challenge of melding this complex, multi-layered man's incredibly disordered life with all the wonderfully perfected photographs he somehow had managed to produce during his four-decade career became an obsession that would consume more than ten years to publication. And all that while, suspended on a wall just above and beyond my computer screen, where my tired eyes could not fail to see her -- whether I was inclined to look or not -- the twisted Tomoko, a blessed child forced to bear the sins of others, an innocent seeming to float under the protective gaze of her mother, served as a constant reminder of the awesome significance of my task. The Tomoko photograph gained worldwide notice when it was first published in Life as the centerpiece of a truncated and, to Gene and Aileen, unsatisfactory earlier version of "Minamata." As it happened, in that same 1972 edition of the weekly picture magazine -- the very vehicle that had provided Gene with his greatest audiences before his dramatic and angry departure in 1954 -- Life reported, in words and full color photographs, what it called the "tragic" results of a fanatic's hammer attack on Michelangelo's "Pieta" in the Vatican, the classic sculpture depicting a crucified Christ being held by the Virgin Mary. It was as if, with the rendering of a new masterpiece directly from contemporary life, the world had come full circle -- and gone mad in the process. And now, these many years later, comes word of another coincidence. At about the same time I learned of the death of the new Life -- an abortive, shrunken, second coming of the once-great weekly in diluted monthly form -- I received the sad news that the Tomoko photograph has been withdrawn from circulation. My first thought was that this palsied but beautiful victim of fetal mercury poisoning, whose wracked body died of pneumonia in 1977, having but reached the age of 21, had had to endure a second passing. In my mind and eye, Tomoko's spirit somehow had continued to live on in Gene's photograph, a symbol of all that was wrong, and right, with the world we humans occupy. Upon first consideration, there is a undeniable logic, an emotional validity, to the decision. The photograph, showing a young, naked, extremely vulnerable child being bathed by her mother in a traditional Japanese chamber, has always been viewed as an extremely private moment made accessible to the outside world by tragedy. But although Gene and Aileen had become close to the family -- had even babysat for the child -- he was, after all, a working photojournalist. And in photojournalism, a certain amount of intrusion is unavoidable, especially when documenting people in crisis. Although he wanted a photograph that would clearly show Tomoko's deformed body, Gene told me it was Ryoko Uemura, the mother, who suggested the bathing chamber. Certainly, she gave the photographer and his young wife permission not only to take, but to use the photograph for purposes she believed could benefit the villagers, and similarly victimized people the world over. This was no grab shot, no stolen moment. The image was planned and set up right down to the use of supplemental flash. Like any good environmental "portrait," this potent picture was an effective collaboration, a visual dialogue, if you will, between subject and photographer. Now, many years after the fact, the father evidently has had second thoughts. "I was told that Tomoko seemed exhausted when she got out of the bath," Yoshio Uemura recently wrote about the strain his daughter must have been placed under. "The photograph went on to become world famous and as a result we were faced with an increasing number of interviews. Thinking that it would aid the struggle for the eradication of pollution, we agreed to interviews and photographs while the organizations that were working on our behalf used the photograph of Tomoko frequently....Rumors began to circulate throughout the neighborhood claiming that we were making money from the publicity, but this was untrue....We never dreamed that a photograph like that could be commercial. [Author's note: knowing Aileen, I doubt she has personally profited much from the picture over the intervening years -- she is more likely to have funneled any income derived from the Minamata photographs right back into the various environmental causes she has continued to embrace in Japan.] "...I do not think," the father continued, "that anybody outside our family can begin to imagine how unbearable the persistent rumors made our daily lives....Although she could not speak herself, I am sure that Tomoko felt that her family were worried for her....She never smiled anymore and seemed to become progressively weaker....Apart from the injections and medicines that lessened her pain somewhat, the only thing that Tomoko had to live for was the love of her family...and it may have been this that allowed her to live as long as she did." In 1997, 20 years after her death, Tomoko's family was contacted by a French television production company wanting to use "Tomoko in Her Bath" in a show about the 100 most important photographs of the 20th century, and to include another round of interviews with the family. In fact, the producers originally had contacted me; in turn, I provided Aileen Smith's contact information in Japan. As a result of her divorce settlement, at Gene's death she had been named sole copyright holder for the Minamata photographs (copyright for the remainder of his photographs rests with his five children). I am sure Aileen referred the producer to Yoshio Uemura, who in this instance not only refused the request for interviews, but balked at allowing Tomoko's image to be, in his view, further exploited. "I wanted Tomoko to be laid to rest and this feeling was growing steadily," he has written. Learning of this decision and his evident distress, Aileen traveled to Minamata to meet with the family. Her response was clearly heartfelt. Aileen Smith agreed to "return" the photograph to Yoshio and Ryoko Uemura, and ceded them "the right of decision concerning [its] use." "Generally, the copyright of a photograph belongs to the person who took it," she subsequently wrote, "but the model [subject] also has rights and I feel that it is important to respect other people's rights and feelings....The photograph 'Tomoko is Bathed by her Mother' [an alternate title] will not be used for any new publications. In addition, I would be grateful if any museums, etc., who already own or are displaying the work would take the above into consideration before showing the work in the future." I certainly appreciate, even share, Aileen Smith's regard for the Uemuras' feelings, and for protecting Tomoko's memory. I'm sure Gene Smith would, too. But my overriding concern is for the precedent that must surely be set by the transfer of control over a photograph, or any work of art, to the subject depicted in that work. I understand about the rights of subjects, living or dead, to have their privacy respected -- at the very least kept safe from callous violation -- and their integrity defended (I have written extensively about the matter, which turns out to be rather complex). That said, however, I also believe that artists, living or dead, deserve to have their rights protected as well. The public, too, has rights to consider, especially when a work has entered our consciousness the way "Tomoko" has. Imagine Michelangelo's aforementioned "Pieta" withdrawn forever from public view. Or Leonardo's "Mona Lisa" having never been seen in the first place because, shortly after it was made, the subject's family felt the painting implied a scandalous affair and demanded its destruction. To address photographic images specifically, consider the effect of deleting Dorothea Lange's migrant mother from the history of documentary work. Or the boy with grenades from Diane Arbus's oeuvre. Or the naked napalmed girl from the history of the Vietnam conflict. As I write this, a startling Alan Diaz photograph of little Elian Gonzales being "rescued" at gunpoint by our government is being analyzed ad infinitum on television and print media worldwide: should the public be denied this knowledge because the image may force the boy to one day relive that traumatic experience? I doubt that any reasonable person would propose eliminating recognizable people from the photojournalistic equation, for instance, but isn't that the next logical step? Yes, the above cited examples were all controversial images of subjects with personal rights. But sentimentality aside, it is always the image that lives on. Unfortunately, it sometimes falls heavily on surrogates to weigh the responsibilities toward the art and the artist against the needs of affected individuals. "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath" was, in my

opinion, Gene Smith's masterpiece, the defining image in a lifetime of

important photographic images. I address this in my book, in a number of

magazine articles and,

Gene Smith's photographs do more than just document particular events, as important as that is. His photographs often provide a glimpse of the future by refracting past and present, giving us a time seen to be as dark as it is bright. "Tomoko Uemura in her Bath" is about much more than Minamata. Today, it has transcended mercury poisoning and the many souls ravaged by the greed of a few. Far removed by time and space from a Japanese fishing village, the photograph, symbolic now, enables people to see in a single image all the possibilities and dangers of life. To me, it is a constant, universal reminder that only through the kind of selfless love depicted in this photograph may the spirit of humanity endure. The image of Tomoko and her mother is as beautiful as it is terrifying. And it is true. This photograph is among the most profound ever made: beyond a particular horror and tragedy, the image has come to represent compassion and humanity. Whether the universal takes precedence over the particular is, of course, a question that may never be answered satisfactorily for everyone. Gene Smith never achieved the perfection he craved for his imperfect life, but he did capture with his camera this one perfect moment of Tomoko and her mother. I have a copy of an old faded snapshot of baby Gene being held similarly by his own mother. If only Nettie Lee Smith had had Ryoko Uemura's capacity for love. "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath" brings Gene full circle, and in a sense completes his life. All good intentions aside, it would be a disservice, I am convinced, to deprive the world, or Gene, of that moment. But if the decision truly is set in stone, then let it thus be carved about this dearly departed photograph: "Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath," R.I.P.

Jim Hughes, founding editor of the original

Camera Arts and former editor of Camera 35 and the Photography Annual,

is the author of W. Eugene Smith: Shadow & Substance, Ernst Haas in

Black and White, and The Birth of a Century. He is a founder and past president

of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund, which administers the W. Eugene Smith

Grant in Humanistic Photography and the Howard Chapnick Grant for the Advancement

of Photojournalism. Hughes can be reached by e-mail at jahjr@pipeline.com.

Text Copyright © 2000 by Jim Hughes

|

Once

back in the states and under the care of a trusted osteopath, Gene slowly

began to recover a semblance of health. One day, he took my wife aside,

intentionally out of my hearing. "Does Jim have a birthday coming up?"

I was told he'd asked. "In about a month," my wife responded. "He never

wears a watch -- does he have one?" Gene wanted to know. "Not one that

works," she informed him. "Then I'd like to get him a wristwatch for his

birthday," Gene announced, with some evident satisfaction at having perceived

a need. "If you really want to give him a gift, I think he'd like something

else," Evelyn suggested. Gene looked puzzled and a little crestfallen.

"A print of one of your photographs would be nice," she said. "A print?"

Gene said. "He'd rather have a print than a watch?" He seemed genuinely

surprised, my wife later told me. Incredulous, even. "Yes," she insisted

to Gene, "a print of 'Tomoko' would please him no end."

Once

back in the states and under the care of a trusted osteopath, Gene slowly

began to recover a semblance of health. One day, he took my wife aside,

intentionally out of my hearing. "Does Jim have a birthday coming up?"

I was told he'd asked. "In about a month," my wife responded. "He never

wears a watch -- does he have one?" Gene wanted to know. "Not one that

works," she informed him. "Then I'd like to get him a wristwatch for his

birthday," Gene announced, with some evident satisfaction at having perceived

a need. "If you really want to give him a gift, I think he'd like something

else," Evelyn suggested. Gene looked puzzled and a little crestfallen.

"A print of one of your photographs would be nice," she said. "A print?"

Gene said. "He'd rather have a print than a watch?" He seemed genuinely

surprised, my wife later told me. Incredulous, even. "Yes," she insisted

to Gene, "a print of 'Tomoko' would please him no end."