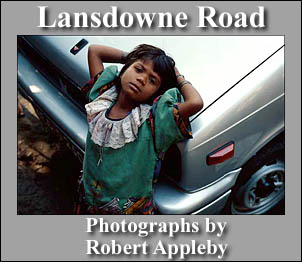

Introduction by Robert Appleby Lansdowne Road is a short street in downtown Bombay, which runs from the 5-star Taj Mahal Hotel to Regal Circle, one of South Bombay's main roundabouts. The area is full of tourists, both foreign and Indian, who come to visit the Gateway of India, a large monumental arch built at the beginning of the last century. It is also where many street people come to try to make a living from the tourists. As well as the street people from all over India there is a large settlement of Pardhis, members of one of the so-called Criminal Tribes, ethnic groups who were "notified" by the British as having a genetic or cultural disposition to crime.

In fact the story of the Pardhis at Gateway is desperately sad. They first came to Gateway, like all other street people, to hunt the tourists (indeed, "pardhi" means "hunter", and their traditional livelihood is hunting), but they were few, just another small group in the mix. Then, several years ago, a British NGO opened a shelter for runaway street kids in Colaba and, not knowing who the Pardhis were, opened their doors to them as well. Naturally this led to an enormous increase in the Pardhi population in Colaba, although the shelter soon decided that they fell outside their remit and stopped helpng them except occasionally in emergency cases. There are now a hundred or more Pardhis at Gateway, living at the bottom of the street hierarchy, despised by the police and other street people, the true outcasts in this extremely stratified society.

Kalya's story is typical. In the early summer the Pardhis go home to their villages to celebrate their festival and patch up their houses. It was June and most of them had already left Lansdowne Road, but Kalya was having no luck with the tourists, and it was a slack period in any case. One day I met him at Gateway and he told me he'd finally got the seven hundred rupees together to go home; his wife was waiting for him in Ulhasnagar, a northern suburb on the mainland, and he was going the next day. The next day I saw a filthy naked man, drugged or drunk, staggering along the street with a group of children laughing and pushing him over. It was Kalya. Abdul, his good friend, told me that while he was sleeping on Colaba Causeway the night before, he was robbed. He'd got hold of some drugs and drink and tried, I think, to kill himself. One day a man with plans, the next a dog to be kicked. We managed to get some money and clothes together for him and send him off to his wife, but it was just the last straw in a long bad six months for Kalya and his family. First his 14 month old daughter Kavita died of viral encephalitis in January, closely followed by his sister Ganga's new baby two weeks later. Then his mother's hip and leg were broken by another son in a drunken fight at Matunga, and Ganga's foot was crushed by a taxi - some said as the result of jaddu - witchcraft. By September his wife was pregnant again. The last I heard (February of this year) he'd stolen a bicycle and run away from Lansdowne Road. What hope is there for a man on the street, where every vestige of decency and dignity is stripped from him.

But few of them have any vision of a better life, even if they had access to it (and the authorities are always after them). Their whole culture by now is centred on begging, although they do sell hair garlands and balloons to tourists and travellers on the suburban trains. And none of them that I know send their children to school, despite the variety of voluntary organisations offering free schooling to street peoples' children in Bombay. Like so many, they are members of India's permanent underclass: people whose limited vision of themselves combines with the indifference and hostility of those above them to perpetuate their condition. |

||||

It

was only after I'd been photographing in Lansdowne Road for a while

that I realised that a group of people who slept in the carpark

and always stayed together when begging actually constituted a tribe.

The other street people - who came from all over India - called

them kachchra lok (rubbish people) although they coexisted peacefully.

It turned out that these were Pardhis, members of one of the so-called

Criminal Tribes, now more properly called the Denotified Tribes

or Denotifieds for short. They came from rural Maharashtra, from

Barsi, although the Pardhi ethnic group is actually spread all over

Maharashtra and Gujurat. Once I had become aware of the Pardhis

staying at Gateway I started noticing them in other places; at Juhu

and Chowpatty, among the crowds on the beaches, young girls selling

balloons and tugging at sightseers' arms; at the stoplights all

over Bombay, always a young girl with a baby whining through the

taxi window with the right hand extended limply for a coin. There

is a large settlement at Matunga on the Central Line, where the

railway slums encroach on the tracks, and the children beg and sell

jasmine blossom hair garlands on the trains.

It

was only after I'd been photographing in Lansdowne Road for a while

that I realised that a group of people who slept in the carpark

and always stayed together when begging actually constituted a tribe.

The other street people - who came from all over India - called

them kachchra lok (rubbish people) although they coexisted peacefully.

It turned out that these were Pardhis, members of one of the so-called

Criminal Tribes, now more properly called the Denotified Tribes

or Denotifieds for short. They came from rural Maharashtra, from

Barsi, although the Pardhi ethnic group is actually spread all over

Maharashtra and Gujurat. Once I had become aware of the Pardhis

staying at Gateway I started noticing them in other places; at Juhu

and Chowpatty, among the crowds on the beaches, young girls selling

balloons and tugging at sightseers' arms; at the stoplights all

over Bombay, always a young girl with a baby whining through the

taxi window with the right hand extended limply for a coin. There

is a large settlement at Matunga on the Central Line, where the

railway slums encroach on the tracks, and the children beg and sell

jasmine blossom hair garlands on the trains.

The

popular image of these tribals still reflects the prejudices that

even scholars have expressed: "Though they have taken to comparatively

peaceful habits, they have not got rid of their thieving propensities.

When in towns or villages selling game, they try to find a suitable

place for robbery. They commit burglaries, rob fields, and steal

when the chance offers." Or again: "Though ostensibly snarers and

hunters, they make their living mainly by committing robberies.

They openly rob the standing crops. Ö They drink liquor to

excess." Kachchra.

The

popular image of these tribals still reflects the prejudices that

even scholars have expressed: "Though they have taken to comparatively

peaceful habits, they have not got rid of their thieving propensities.

When in towns or villages selling game, they try to find a suitable

place for robbery. They commit burglaries, rob fields, and steal

when the chance offers." Or again: "Though ostensibly snarers and

hunters, they make their living mainly by committing robberies.

They openly rob the standing crops. Ö They drink liquor to

excess." Kachchra.

At

one time things were different: the Pardhis were entertainers and

animal handlers in the courts, and were sometimes rewarded for their

performances with grants of land - grants which now have no legal

validity. About the only trace of their former profession is the

common use of monkeys as begging accessories. As for the land, on

which they built their villages, that is being eaten up by the explosive

growth of the cities, which no group of impoverished tribals can

halt, no matter what old documents say.

At

one time things were different: the Pardhis were entertainers and

animal handlers in the courts, and were sometimes rewarded for their

performances with grants of land - grants which now have no legal

validity. About the only trace of their former profession is the

common use of monkeys as begging accessories. As for the land, on

which they built their villages, that is being eaten up by the explosive

growth of the cities, which no group of impoverished tribals can

halt, no matter what old documents say.