|

THE BIGGER PICTURE

Nick Ut recalls

the Events of June 8, 1972

by Horst Fass and Marianne Fulton

By

1972 most U.S. helicopter units had left Vietnam. It had become

more difficult for reporters to reach the isolated areas where South

Vietnamese troops, often surrounded by communist guerrillas and

regular north Vietnamese soldiers, were fighting. It was a time

when AP photographers had to travel the dangerous roads leading

out of Saigon, Danang or Pleiku towards areas where fighting took

place. By

1972 most U.S. helicopter units had left Vietnam. It had become

more difficult for reporters to reach the isolated areas where South

Vietnamese troops, often surrounded by communist guerrillas and

regular north Vietnamese soldiers, were fighting. It was a time

when AP photographers had to travel the dangerous roads leading

out of Saigon, Danang or Pleiku towards areas where fighting took

place.

At dawn of June 8, 1972, about 5 AM,

photographer Nick Ut loaded his camera gear, field survival kit,

flak-jacket and steel-helmet into one of the AP's Japanese made

minibuses (the AP correspondents called them 'command modules')

parked outside the Eden Building, where the AP's Saigon office was.

He wore a Vietnamese Marines style uniform with the nametags 'Bao

Chi' (for 'Press'), Nick Ut and Associated Press. He carried no

weapon. The vehicle had an assigned Vietnamese driver, who would

always stay with the car, while the photographer would usually wander

off with troops.

Nick

travelled alone that day, without a correspondent. It had been reported

that traffic on Route-1 had been interdicted by North Vietnamese

troops - and it was Nick's assignment to reach the South Vietnamese

units that had been sent there to engage the enemy and re-open the

road. Nick asked the driver to head north - west, past Tan Son Nhut

airport and onto Route-1, which leads from Saigon towards the Cambodian

border. Nick

travelled alone that day, without a correspondent. It had been reported

that traffic on Route-1 had been interdicted by North Vietnamese

troops - and it was Nick's assignment to reach the South Vietnamese

units that had been sent there to engage the enemy and re-open the

road. Nick asked the driver to head north - west, past Tan Son Nhut

airport and onto Route-1, which leads from Saigon towards the Cambodian

border.

At the city limits both Nick and the

driver put on their flak-jackets: the open areas between villages

along Route-1 with their paddies and hedgerows were sniper territory.

Their vehicle soon mingled with buses and commercial vehicles which

also set out for travel at day break. During the night the roads

were unsafe and abandoned.

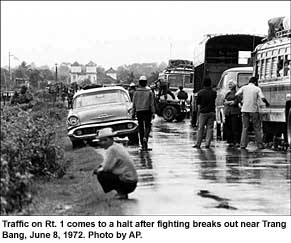

By 7:30 AM Nick Ut had reached the

outskirts of the village Trang Bang (about 25 miles WNW of Saigon)

and his driver joined a long queue of waiting vehicles: Less than

a mile away North Vietnamese troops still controlled a section of

Route 1 in Trang Bang. Soldiers of the Vietnamese 25th Division

had fanned out around the village and tried to sweep through it.

"We

passed hundreds of refugees fleeing the village. They cooked and

slept outside the village, hoping to return when the fighting stopped.

It was the third day of fighting in the area." Ut later reported. "We

passed hundreds of refugees fleeing the village. They cooked and

slept outside the village, hoping to return when the fighting stopped.

It was the third day of fighting in the area." Ut later reported.

Nick left the car, introduced himself

to one of the battalion commanders and then joined the troops. There

were some firefights and casualties ensued. As the troops approached

the village across the paddy fields civilians emerged to flee towards

the South Vietnamese lines. Nick Ut was instantly at work, photographing

the soldiers, desperate refugees and early artillery and air-strike

support for the soldiers whose advance had stalled.

About noon the field commander of

the Vietnamese troops outside Trang Bang asked for additional air

support from South Vietnam Airforce units based at Bien Hoa, some

15 miles away. Nick made his way back to Route-1, waiting

like the soldiers, the travellers caught in their cars in the traffic

jam outside Trang Bang, and a flock of other reporters for the planes

to arrive and perform their bombing runs. A yellow smoke grenade

was thrown by a soldier marking the target area for the approaching

Skyraiders, Korean-war vintage planes. Trang Bang had fallen silent

- and the speculation was that the North Vietnamese and their Vietcong

allies had already withdrawn - a pattern familiar to experienced

observers of the war.

When the planes arrived overhead at

about 1:00 PM reporters and soldiers stood upright, watching. Nobody

at that time believed that even communist snipers were left behind.

The monsoon rain had stopped.

Nick met fellow reporters and friends

who like him frequently ran the dangerous roads to find battles:

There was David Burnett, from Time Magazine, Ut's Vietnamese photographer

friend Hoang Van Danh, a freelancer who would work for both United

Press International (UPI) and AP (he now lives in Switzerland) and

television teams from the BBC, ITN, NBC and other news organizations.

The rest is photographic history:

The two Skyraider aircraft of the VNAF bombed the edge of the village,

near the Cai Dai pagoda, in a familiar pattern - first explosive

bombs, then incendiary bombs - large containers with a mix of explosives,

white phosphorus and the black oily napalm - and ending up with

heavy machinegun fire during closing strafing runs. Then the planes

disappeared - nobody had heard any anti-aircraft fire. And

then the terrified, burned and wounded villagers came running from

the village, towards the line of soldiers and reporters standing

across the road.

Nick Ut recalled in a 1999 interview:

"When we (the reporters) moved closer to the village we saw the

first people running. I thought 'Oh my God' when I suddenly saw

a woman with her left leg badly burned by napalm. Then came a woman

carrying a baby, who died, then another woman carrying a small child

with it's skin coming off. When I took a picture of them I heard

a child screaming and saw that young girl who had pulled off all

her burning clothes. She yelled to her brother on her left. Just

before the napalm was dropped soldiers (of the South Vietnamese

Army) had yelled to the children to run but there wasn't enough

time."

Nick Ut used two cameras to photograph

the scenes in front of him - his Leica and a Nikon with a long lens.

Not far from him stood NBC cameraman

Le Phuc Dinh, who along with Ut is credited to have produced the

best documentation of Phan Thi Kim Phuc's desperate run down Route-1.

Le Phuc Dinh, who is shown at work in one of Nick Ut's pictures,

used a 16mm film and sound camera.

Both David Burnett and Hoang van Danh

changed film in their cameras during the peak moments of the action.

Danh managed a few pictures when Kim Phuc had reached the line of

photographers and soldiers and sold a few of them to UPI.

"Nicky, you got all the photos," said David Burnett.

Nick Ut recalls that Kim Phuc screamed

"Nong qua, nong qua" ("too hot, too hot") as he photographed her

running past him. When the girl had stopped Nick Ut and ITN correspondent

Christopher Wain poured water from their canteens over her burns.

Kim Phuc's relatives gathered around

her and the reporters. Nick Ut heard her saying to her also injured

older brother Phan Thanh Tam, "I think I am going to die." (Tam

is seen in Ut's award winning picture, running alongside her, at

left).

Kim Phuc's parents were still hiding

inside the Cao Dai pagoda.

Urged on by Kim Phuc's uncle, Nick

commandeered his car, and being one of the few reporters able to

communicate with the injured villagers he took over and carried

Kim Phuc into the car. Then other members of her family - her younger

brother Phan Thanh Phuoc (5), her older brother Tam (13), her uncle

and an aunt rushed into the car. Ut climbed aboard the now overcrowded

minibus last and ask the driver to speed towards the provincial

Vietnamese hospital in Cu Chi, halfway to Saigon. "I am thirsty,

I am thirsty, I need water" Kim Phuc continued to cry. When the

van moved Kim Phuc screamed out loud, obviously in great pain and

then lost consciousness. Nick, beside her, tried to console her

saying "don't worry, we will reach hospital very soon."

They reached the hospital within the

hour. The doctors and nurses there had seen and treated burn and

shrapnel wounds for many years. Even in situations when the hospital's

emergency wards were suddenly overcrowding with war injured an atmosphere

of quiet medical professionalism prevailed rather than panic and

confusion. Nick Ut knew very well that the doctors would attend

first those whose lives could most likely be saved, and put others,

who were expected to die, aside for later treatment. It was

a battlefield experience Nick Ut had often shared with soldiers

and civilians alike.

He pleaded with the doctors and nurses

to take care of Phan Thi Kim Phuc - and they did. Ut told them what

he had seen on Route-1, what he had photographed and that he expected

his pictures to be published everywhere.

Only when Kim Phuc was on the operating

table did Nick Ut leave the hospital and head towards Saigon, to

bring his film to the AP.

When a newsman later de-briefed Nick

Ut for a by-line story of what he had experienced on Route-1, Nick

did not mention that he helped Kim Phuc.

It was 28 years later, in London,

that Kim Phuc said in front of the Queen: "He saved my life."

|