An

Affair of the Heart

Learning French requires humility. During my first week in Paris, I committed my first major gaffe. I had been walking past a very Brassaï-like proletarian café every day, and I longed to drop in and mingle with the hefty, bloody-aproned butchers who frequented the place. One day I mustered enough courage. Before entering, I repeated at least five times, "Monsieur, je voudrais une bière" ("Sir, I’d like a beer"). Confident I had it down, I strolled in, planted myself at the center of the zinc bar, and blurted out, "Monsieur, je m’appelle bière" ("Sir, my name is beer"). I didn’t understand the butchers’ howling laughter until the bartender looked at me calmly and said, "So, Mr. Beer, what would you like?" I’ve laid in bed many a night wishing I’d been so smooth as to respond, "Un café crème, s’il vous plait." I was immediately captivated by the dynamic energy of my new city. During the mid-1970s and early ’80s philosophical and ideological debate was a fundamental and active part of the Paris scene. French political life encompassed a plurality of strong beliefs, with the electorate split down the middle between the left and the right. There were frequent labor strikes, numerous student demonstrations, and much political agitation. It was the height of the Cold War, and given the centrality of Paris to Europe, just being there made me feel in close contact with world affairs. I remember vividly the mass protest marches in Paris when the Russians entered Poland in 1981. All of this was a strong stimulus for my young spirit. I had first picked up a camera at the age of seventeen, and photography immediately opened up my world. From the beginning, it was a way to show others what I cared about and a wonderful pretext for me to enter new worlds. While I was stuck in the hospital with a knee injury from high school football, my parents gave me a book by the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. His work helped me to discover glory among the common moments of daily existence. The legendary lives of so many photographers for whom Paris had been a central theme fascinated me, and I was especially inspired by the rich visual traditions of Atget, Brassaï, Izis, and Kertész. I’d spend evenings in the basement of our house in Indiana, printing my latest photos and dreaming about how Robert Capa had made his famous Spanish Civil War photo when he was just twenty-one. I knew he had invented himself as a photojournalist in Paris. In The Family of Man, the book that became my bible of photography, I discovered Robert Doisneau and Edouard Boubat, both of whom would later become not only important sources of inspiration but also members of my extended family. In fact, one of my first personal encounters with the great photography of France came when I called on Boubat. In 1973 the American magazine 35mm Photography devoted twenty pages to a year-long photo-essay that my twin brother, David, and I had made about life on McClellan Street in the inner city of Fort Wayne, Indiana.

One day during my early years in Paris, I was in the Luxembourg Gardens when a man walked by and photographed me sitting on a bench with a girlfriend. I ran after him, curious to get a better look at the beat-up Leica he was carrying. He turned out to be the great Czech photographer Josef Koudelka, who had just arrived in Paris with his epic body of work on Eastern European Gypsies. I was deeply moved by his images, and his lifestyle taught me to appreciate the spirit of a nomadic existence. Throughout my first nine years in Paris, the life of this city was my only photographic preoccupation. I walked the streets tirelessly. One Sunday morning I left my garret apartment on the Ile de la Cité, and while crossing the bridge to the Ile Saint-Louis I noticed an old man moving along the sidewalk, discreetly holding a small Leica camera. I recognized that he was André Kertész, the magnificent Hungarian photographer and quintessential cosmopolitan, who had spent almost half his life photographing Paris and the other half, New York. We had previously met at his Manhattan apartment next to Washington Square, and he recognized me when I called out to him. After I told him about my garret with its view of Notre-Dame he wanted to take a look. Once on my balcony, he studied the cathedral and then turned to tell me that the light was not interesting and asked if I understood the importance of light. Until that moment, I had often been struck by the beauty of light, but after this I learned to contemplate it and allow it to make my life richer. During my first three years in Paris, I worked as a printer at Picto, the celebrated lab where Cartier-Bresson’s pictures are printed. Simultaneously, I continued graduate studies in international relations at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques. Each morning at the lab I was surrounded by printers who devoted their lives to communication through black-and-white photographs. I immersed myself in images by many of the world’s greatest photographers, including Lartigue, Cartier-Bresson, Koudelka, and many of the Magnum photographers. Each afternoon at "Sciences Po," which trains most of France’s political leaders and much of its ruling class, I was exposed to the elite world of French academics and the haute bourgeoisie. Soon after receiving my diploma, when my professional future was still uncertain, I met Robert Doisneau and showed him a set of my Paris images. This encounter had a profound impact on my life, for he asked if I would be interested in helping him print his pictures and offered to introduce me to the director of Rapho, his photo agency. I embraced both opportunities and soon found Doisneau to be even warmer as a person than as a photographer and an inspiration in all ways. Very frequently I would take the metro to his home in the working-class suburb of Montrouge, where I would spend the day printing his human and tender photographs of Paris. I’ll never forget seeing Doisneau cover for his aging concierge each morning by taking out the building’s garbage. The concierge had once been his assistant, and he risked losing his ground-floor apartment if the other tenants realized that he was incapable of carrying out his duties. In addition to his incredible generosity, Doisneau taught me the power of hard work, patience, and meticulous organization. At about the same time, Rapho began to offer me regular assignments for major international publications, including the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and many French magazines. I quickly learned to satisfy the needs of these publications while also following my own journalistic instincts and passions. In 1984 Newsweek sent me to India to cover Indira Gandhi’s funeral and the ensuing sectarian violence. This first foreign assignment changed my life. I developed an insatiable desire to travel and to document people whose plights deserve the world’s attention.

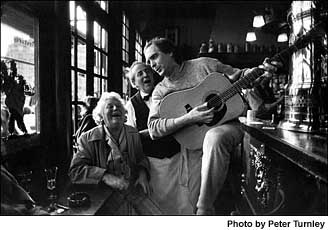

Having lived most of the past two decades far from my immediate family, I’ve found a sense of family spirit at many of my Parisian haunts. In particular, I’ve been able to count on the warm and human ambience of the Brasserie de l’Isle Saint-Louis. This restaurant, and life in several Paris cafés, is the subject of many of the photographs that follow. Many of the people who have contributed to the life of this city weren’t born here, and so the "Parisians" of my title encompasses anyone living in Paris. I haven’t attempted to present an encyclopedic view of the city, nor have I tried to explain my photographs with words. Rather, I want to share a mosaic of images that express what I feel and cherish about this extraordinary place and its people. Though constantly changing, Paris always moves my heart.

|

When

I arrived in Paris twenty-five years ago, at the age of nineteen,

the city I encountered sang to my senses. My heart and mind were

immediately stimulated by its light, vibrancy, and texture. The

French language entered my ears like music, and suddenly communication

seemed not merely functional but a celebration of feelings. I quickly

grasped that in order to understand Parisians I would have to speak

French well; otherwise, I would never be able to get to know the

beautiful, mysterious women I was seeing everywhere I looked.

When

I arrived in Paris twenty-five years ago, at the age of nineteen,

the city I encountered sang to my senses. My heart and mind were

immediately stimulated by its light, vibrancy, and texture. The

French language entered my ears like music, and suddenly communication

seemed not merely functional but a celebration of feelings. I quickly

grasped that in order to understand Parisians I would have to speak

French well; otherwise, I would never be able to get to know the

beautiful, mysterious women I was seeing everywhere I looked. In

the same issue there was a portfolio of Boubat’s pictures.

Two years later I arrived at his Paris apartment with the magazine

in hand. That first meeting was the beginning of a friendship that

would grow for the next twenty-four years. Edouard’s humanity,

humility, and love of life had a contagious effect upon me and everyone

else he encountered. For the better part of ten years, until his

death in 1999, we would meet at least once a week for an afternoon

glass of rouge and warm conversation at the old wine bar La Tartine,

on the rue de Rivoli. Boubat’s spirit touched me in profound

and inspiring ways, as did his photography. His work always highlighted

the beautiful and the good, while his life always demonstrated the

courage to confront difficulty with grace.

In

the same issue there was a portfolio of Boubat’s pictures.

Two years later I arrived at his Paris apartment with the magazine

in hand. That first meeting was the beginning of a friendship that

would grow for the next twenty-four years. Edouard’s humanity,

humility, and love of life had a contagious effect upon me and everyone

else he encountered. For the better part of ten years, until his

death in 1999, we would meet at least once a week for an afternoon

glass of rouge and warm conversation at the old wine bar La Tartine,

on the rue de Rivoli. Boubat’s spirit touched me in profound

and inspiring ways, as did his photography. His work always highlighted

the beautiful and the good, while his life always demonstrated the

courage to confront difficulty with grace. Travel

has been my way of life for many years now. As a contract photographer

for Newsweek during the last seventeen years, I’ve worked in

more than eighty-five countries, speeding to almost every war, revolution,

natural disaster, famine, and genocidal conflict. Trying to communicate

the human dimension of world events has exposed my sense of inner

peace to countless horrors. The one constant in this often wrenching

and frenetic existence has been that I always return to Paris, and

the city is always the key to my recovery. The elegance and warmth

of the Parisian art de vivre has always offered a soft landing from

painful experiences my heart might prefer to reject.

Travel

has been my way of life for many years now. As a contract photographer

for Newsweek during the last seventeen years, I’ve worked in

more than eighty-five countries, speeding to almost every war, revolution,

natural disaster, famine, and genocidal conflict. Trying to communicate

the human dimension of world events has exposed my sense of inner

peace to countless horrors. The one constant in this often wrenching

and frenetic existence has been that I always return to Paris, and

the city is always the key to my recovery. The elegance and warmth

of the Parisian art de vivre has always offered a soft landing from

painful experiences my heart might prefer to reject.