"You're free," said Wen Ho Lee's attorney, as they walked out of the federal courtroom in Albuquerque, New Mexico. "Sign my shirt!" asked a man with a felt pen, and the attorney obliged as the wispy nuclear scientist, now a convicted felon, smiled shyly. Outside under a sun that was too hot, the US Attorneys who had prosecuted the case stood at acluster of microphones to answer questions. Finally willing to speak to the media after months of offering no comment, they doggedly stated and re-stated their position, the sweat rolling down their faces. Eventually the prosecutors gave way to the victorious Dr. Lee, who walked the media gauntlet while cradled under the arm of Mark Holscher, one of his lawyers. The diminutive center of attention made his now-famous declaration: "I'm going fishing!" I'd been working on this story since March 8, 1999 when Wen Ho Lee was dismissed from Los Alamos National Laboratory. I'd stood across the street from his home in the rain, wind and snow, hoping to get a response from the naturalized citizen from China. A young reporter named Sergio Quintana shot some video of Dr. Lee about a month later, as the accused scientist wandered in his front yard, wearing a goofy fishing hat while the F.B.I. searched his home. '60 Minutes' interviewed Wen Ho Lee and 'Dateline' went fishing with him, grabbing shots of federal agents dashing between trees on the Chama River. CNN profiled the Lee children, Alberta and Chung. We got the word in December that Wen Ho Lee would be indicted, and stood on the curb, waiting for a couple of days, until federal agents took him into custody. ("Have you been indicted?" pipes my voice on the video clip. At least I didn't ask him, "How do you feel?"). There were two bail hearings in U.S. District court in December 1999 in Albuquerque. A third bail hearing was heard in August 2000. When F.B.I. Agent Robert Messemer recanted his testimony from earlier hearings, the road to Wen Ho Lee's release began to widen. The August hearing, scheduled for one morning, dragged on for three days. During lunch, courtroom sketch artist Amy Stein described her drawing technique to a few reporters. Amy peers at her subject in the courtroom through binoculars, getting "up close and personal" with the face and psyche of each person she draws. Her insights intrigued the writers who were already fascinated with the personalities of those who speak in court, and those who listen attentively as their fate seesaws on the scales of justice. Back in District Court, we tried the snack room where green chile was served with almost every dish. Staci Cohen, the Lee's designated family spokesman, explained to me why she was angry at 'Good Morning America.' I thought it best to distance myself from that program–I am working for World News Tonight, thank you very much. In court, the lawyers debated semantics, differing on the precise meaning of an "attachment" to a search warrant. Feeling heavy lidded, I asked a reporter to wake me if I started drooling in my sleep. I've had enough brushes with detention on assignment to make me really want to avoid being in contempt of court.

As testimony became more arcane and tedious, the out of town press phoned their travel desks during each recess, to change their flights home. They moved back their flights, and back again, until everyone gave up the early flight home that would have enabled them to be with their kid, or to start their family vacation.

One day my pager went off in court, (in vibrate mode, of course) and I stepped out of the courtroom to make my call. It was Steve Northup, a friend of mine from Santa Fe. "Are you in court?" he asked. "I figured you would be and I was wondering if you could give me directions." Steve was assigned to shoot a picture of Wen Ho Lee's daughter Alberta, for a New York Times portrait. During the next recess, I told the New York Times reporter, "Your photographer is on his way." "How did you know that?" "This," I replied, "is a small town." Throughout the course of the Wen Ho Lee case, I called the Assistant U.S. Attorney George Stamboulidis several times a week. He took my calls, but was consistent in replying "no comment." I asked about procedure, about plea bargains, about the prosecution's case. "No comment," he said. During the hearing I hopped in the elevator with the Assistant U.S. Attorney. So did other reporters, who peppered him with questions. Finally, Stamboulidis pointed to me and says, "ask her." Inquiring minds turned to me as I recited, "No Comment." A day in September, another hearing for Wen Ho Lee. I was working with two freelance crews, looking for a grab shot of the arrival of the convoy bringing Dr. Lee to court, from prison. I got a call from the assignment editor at channel 7, our affiliate who said, "Look for a green Ford LTD." I heard a helicopter and told my crew the convoy would soon arrive. They grabbed the shot, and I called Channel 7 to advise them that their information was good. "How did you know that he was in that car?" I asked. "Oh, we were watching it on TV, on Channel 4," he told me. Sunday September 10, I was just home from a horseback ride when my cell phone rang. Judge Parker's clerk told me that a guilty plea had been filed. Unable to reach any of the principals on the phone, I hurried downtown to try to confirm that it would be one felony count. The defense attorneys' law office was closed. I decided to check for activity at the U.S. Attorney's office. There I noticed the F.B.I. agent who changed his testimony. I walked with him for several blocks, having another one of my one-sided conversations, in which I asked many questions, and heard no answers. I returned to my car, just in time to see the U.S. Attorney for the District of New Mexico standing on the street corner in something resembling running shorts. I strolled over in my old t-shirt, and horrible baggy pants, for a chat. The U.S. Attorney did not dash away. "This is a small town, " I concluded. Actually this is a town where Domino's doesn't deliver pizza to the ninth floor of the U.S. Attorney's office. Norman Bay was waiting for a car to pull up with one sausage and one mushroom pizza. Second Street in downtown Albuquerque was quiet, except for one field producer talking to a prosecutor waiting for pizza. 4AM, September 14th. Wen Ho Lee was a free man, and his attorneys and family arrived for their live shots on Good Morning America. Staci Cohen was present, but the grudge against GMA had been left behind. I was gratified when defense attorney Mark Holscher told Charlie Gibson, by satellite before the shot, "I'm only up this early because Amy is so nice." "Who is Amy?" was Charlie's reply. New York City is not a small town. Later in September, I stopped by Wen Ho Lee's residence near Los Alamos with an offering for Dr. Lee. He had requested extra fruit during his long incarceration that is now being investigated in Senate Hearings. I gave Mrs. Lee a bowl of fruit, and apologized for standing in front of their house for a year and a half. I explained that I had been doing my job, but I felt sorry to have to do it that way. "Thank you, and please thank everyone at ABC," she said. Again, I explained that there is no need to thank me, that it was part of my job. I have the feeling I'll be seeing Wen Ho Lee's attorneys, the convicted scientist, the witnesses, the F.B.I. Agents, and probably the Judge again. This is a small town. Amy Bowers

|

|||||

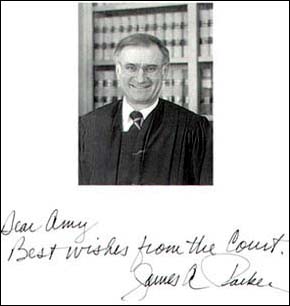

While

the hearing progressed, a Washington producer asked me for a

headshot of Judge James A. Parker. I arranged to pick up a glossy.

Judge Parker's deputies buzzed me through two sets of doors,

and lent me their only 4"x6" print. I copied it and brought

it back to the court. In walked Judge Parker, so I said "hi"

and we had a short conversation. Then I asked him to autograph

one of the headshots.

While

the hearing progressed, a Washington producer asked me for a

headshot of Judge James A. Parker. I arranged to pick up a glossy.

Judge Parker's deputies buzzed me through two sets of doors,

and lent me their only 4"x6" print. I copied it and brought

it back to the court. In walked Judge Parker, so I said "hi"

and we had a short conversation. Then I asked him to autograph

one of the headshots.