|

"G'Day's in Australia"

Horst Faas reports from the "There was no pushing and no shoving, and nobody got in the way. It was the easiest 100 meters ever. Just as the participants and the organizers scripted it. The pictures were exactly what we expected." Thus, Gary Hershorn, the veteran Reuters photographer, picture editor and planner of many Olympic Games summed up the photo coverage of the 100-meter runs for women and men, a highlight of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games.

The ease with which the 100-meter races could be covered was symptomatic for each event, and at each sporting venue. More than a thousand photographers went through the grueling 17-day schedules of the Games and there were none of the complaints so familiar during previous Olympics, none of the hurdles that made life miserable for the photographer who had to rush from one event to the next. Everything went so smooth that Olympic old timers were almost suspicious. As an Associated Press photographer and editor, I have covered the Games, summer and winter, since 1972. For a second time, I am the coordinator of the International Olympic Photo Pool (IOPP), which is made up of the three agencies: Agence France Press, Associated Press and Reuters Photos. The daily meetings of the IOPP member agencies with officials of the Olympic Organizing Committee were, in the past, lengthy and often bad-tempered griping sessions, about bad photo positions, missed opportunities to get the right pictures, obstructive venue managers, lack of transportation, daily fights for the limited space available for photographers, and the hours of queuing for special passes for the swimming, men's basket ball finals and other competitions. None of that in Sydney. The daily IOPP 12:30 meetings with Sydney photo chief Gary Kemper and his adjutants were brief, friendly affairs sorting out who would ride the motorbike ahead of the marathon runners, or who would shoot from the rafter of the stadium during the opening ceremony. "Is there really nothing wrong here, is there nothing we should complain about?" questioned AP's Mike Feldman halfway through the Games. No, nothing, was the comment of the other agency representatives. Day after day, meeting after meeting, all remained well and everybody smiled. Sorry, no complaints. By Day 14, two highlights among "complaints" concerned an agency Pool photographer who had taken off his shoes and socks during a basketball preliminary game (with the aggravated charge that he had smelly feet), and a British photographer who had taken a packed sandwich and a soft drink to his pool position and proceeded to have his lunch during the event. Another day, the sole problem was the Pool's road cycling motorbike rider who insisted that the photographer should sit on the bike looking backwards, a practice which the experienced Tour de France photographers have abandoned a few years ago, after it led to accidents. The stress of the Sydney Games came from the fact that there was no stress. Some photo editors and managers almost seemed to miss the good old fights, the arguments and the occasional disasters that would stir the adrenaline. Sydney 2000 became a veritable festival of photojournalism. While television ratings plummeted and stirred some controversies in Australia, the Sydney 2000 Games have become the best photographed Games ever. For the very competitive Australian press the Olympic Games are the biggest event ever covered in the history of Australia. Never before has coverage been so meticulously prepared. "We have 36 photographers on the job for the Olympics," said Julian Zakaras, the photo boss of Rupert Murdoch's News Ltd. "Everybody knew for weeks exactly what we wanted them to do. We took the test events very seriously and are now getting what we prepared for." Australia's major newspapers are either in the camp of News Limited (the tabloid The Daily Telegraph, the Sunday Telegraph, the Australian and other papers in each of the six Australian states), or with the Fairfax Group (Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Age). Their lively competitiveness resembles very much that of the British press, or the competition which took place back in the days when American cities had two or more morning and afternoon papers. During these Olympics they fought it out with special editions, day-by-day photography souvenir insert pages, and ever larger and better displays of superb sports photography, including double-page panorama photos. One looked, during breakfast, into the Sydney Morning Herald and the Daily Telegraph to see and read what happened during the previous late night hours. News photography is indeed alive and well in this newspaper city. Television can't match the drama displayed and written about in everyday papers. Circulation figures of the Sydney papers rose by 15% during the early days of the Games. They continued to rise as Australian sportsmen and women reaped more medals. The biggest story was the Australian athlete Kathy Freeman, an aboriginal indigenous Australian runner, who lit the flame and stopped traffic in Sydney when she won the 400-meter race. The papers came out with special editions to report a press conference she gave after her victory. "During all previous Olympic Games we measured our performance with the British and the American Press," said John French, a picture editor with the Sydney Morning Herald. "This time we are the object of envy, we even had foreign photographers telling us how much they would love to work for a paper like ours." Gary Kemper, 49, a native of Nebraska, attributes the obvious success to the three years of meticulous preparations and planning and the good cooperation in the beginning stages. "We had an early start: when the plans for each venue were drawn up the photo chief was consulted and we sat together with television representatives to design photo facilities that are definitely an improvement over the past and yet did not conflict with television, nor the interests of sports the federation and spectators. "We were listened to, and not much had to be repaired after construction was completed." Gary Kemper, who previously held the position of the Olympic photo Chief in Atlanta, brought Olympic experience to Sydney dating back to Sarajewo (1984), when he was with UPI. In Seoul 1988, he was the IOPP Coordinator, and in Barcelona 1992, consultant with Kodak, assigned by the International Olympic Committee. He started in Sydney three years ago. "We tried to maximize the best space possible for still photographers. We could hold on to all our traditional photo positions and are getting the most out of them now. We could also add some positions and make it possible to file from these positions. The moat around the field of the main stadium is now comfortably wide, we established tiered platforms at gymnastics and other venues. With improved designs in the detail we ended up with fewer or no problems." Russell McPhedran, a Sydney photographer who has covered Olympic swimming for more than 30 years, said about the photo facilities at the Sydney Aquatic Stadium, "this time they got it right. Especially at the swimming we always had headaches. This time no hassles at all, easy work and excellent pictures. No waiting and fighting for passes. Work was a pleasure."

The cheerfulness of the close to 700 venue volunteer workers - many of them unpaid and some of them backpackers, grannies and retirees - was infectious. The "G'Day" and "Howyahgoin' mate" sounded so much more honest than the "Have a nice day" of Atlanta. As the Games progressed, praises for the Sydney organizers from hardened and often cynical Olympic veterans abounded. The 2000 Olympic Games were covered by 1,077 photographers, just about as many as in Atlanta. The three big agencies: AFP, AP and Reuters brought in a total of 161 photographers a greater number than in the past - as more sports have been added. Among the additional events: triathlon, women's weightlifting, and Taekwondo. AllSport agency, owned by Getty, has 24 photographers in Sydney, by contract with the I.O.C. AllSport has sole commercial rights for photographs taken at the Games. All other photographers have to sign a pledge to use photographs for editorial purposes only. At Sigma agency photographers with Corbis logos were spotted. Corbis, the other major stock agency, has bought Sigma since the Atlanta Games. Corbis' owner, Bill Gates, was among the VIP spectators at the opening ceremonies and several venue events. The Australian papers had accredited just over 100 photographers. All other accreditations were handed out - as usual - via the national Olympic Committees, lead by photographers from the U.S.A. (184), Japan (158), Germany (150), the U.K. (144), France (147), Canada (120). The Olympic Games leave no room for freelance photographers, unless they work for a major newspaper, magazine or agency. The media population in Sydney also included some 3,500 writers and editors, and just about as many technicians. Television rights holders sent almost 12,000 people, an incredible number. Their headquarters was the International Broadcast Center, inaccessible for all the "normal" media people. Most competitions were held in the isolation of the venues in the Sydney Olympic Park, west of Sydney, a city of three million. Others were held in Brisbane and Melbourne. Some spectacular events took place against the dramatic backdrop of Sydney Harbor. When the triathlon swimmers crossed the harbor it looked as if a school of large fish were invading the skyscraper waterfront of Sydney, behind the City's landmark Harbor Bridge. During the sailing competition some of the sails beautifully matched the roof architecture of the Sydney Opera House. While sponsors and some television people could stay in hotels or in luxury cruisers anchored in Darling Harbor, the mass of the press corps was housed in a vast fenced in compound with prefabricated huts, called alternately the "Gulag" or "Australia's answer to Soweto." Stories had it that it was once a mental asylum. The bus ride to the Olympic Park did not reveal any of the pulsating life in this great city, especially as the bus rounded the biggest cemetery in Australia, dating back to the days when convicts from England arrived here. But there were other diversions: On the way to the bus stop, journalists could walk past a little zoo with an aviary full of Australia's rich and varied bird life. White, pink and black cockatoos, crimson rosellas, rainbow corikeets and king parrots were caged for the benefit of the world press. The displayed birds became a gathering place for the many other, still free wild birds - attracted to their kind behind bars. Birdwatching took on real meaning in Sydney. Next to the aviary was an enclosure with samples of the unique Australian wildlife: Kangaroos of several varieties, swamp and agile wallabys, emus. But no crocodiles. Those correspondents feeling more adventurous could get even closer acquainted with the wildlife of Australia through the menu card of Edna's Press Table restaurant at the Main Press Center. The excellent nouvelle cuisine of old Australia included crocodile in wafer-thin pastry with spinach, grilled wallaby served with luscious and fleshy red Rosella blossoms, very tender Kangeroo grilled or pan-fried, raw Emu steak tartare with bush tomato and pepperberry, wild quail with quail eggs served on an outback salads - or, for the more traditional taste: a "carpet beggar" filet steak, filled with raw oysters. Edna's cuisine tries to revive some of the unique and special Australian indigenous tastes and flavors - which, of course, go well with the now large selection of Australian wines growing up and down the south Australian coast. Australia was worth the 26-hour trip in a tight airplane seat. Sydney is a city many like to visit again. Except for a quick train ride into the city center, few of the press people saw much of Sydney. There have been nasty rumors that the Games may return to Sydney if the Athenians don't get their act together. The other rumor is that the MPC may be built adjacent to the Parthenon. At least we would see more of Athens. The Games have become big and bigger. As sports are added, the number of athletes and press people grows. That alone deserves a re-think of the Olympic Games. Progressing technology is another problem which needs to be tackled by the Press Commission of the International Olympic Committee. The IOC will come under pressure from advertisers and readers to release more content to the Internet for future Olympics. The IOC's current policy of denying media credentials to online journalists, and preventing live Olympics coverage online may have to change before the 2002 and 2004 Games. Under IOC rules for the Sydney 2000 Games, video footage is restricted to the U.S. broadcaster NBC's Olympic website, and any online footage must be shown on television first. Most of NBC's broadcasts were delayed, often long after still photos had already been published. The IOC rules regarding video coverage for 2000 exclude all but NBC's video coverage. If any photographer decided to use a still-cum-video "Platypus" camera for video coverage of the Games, any use of that video would be illegal and become a serious matter for the lawyers of the IOC. And if noticed, a "Platypus" would loose the IOC or Sydney Olympics Organization's accreditation. Although the native Australian platypus is one of the three mascots of these Games platypus-type coverage is a definite no-no. The Press Commission has yet to put this issue on their agenda. Horst Faas

|

|||

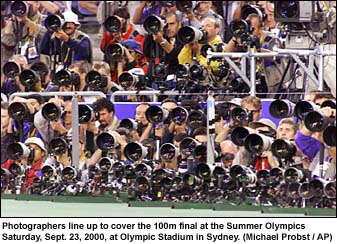

Hundreds

of 400 to 1200mm long lenses faced the finish line, many more

followed the runners from their starting blocks from both sides

along the 100-meter track. When the winners ran their lap of honor,

agency and Australian newspaper photographers were handling their

laptops while in their positions, and transmitted selective pictures

on standby ISDN lines. Others simply transmitted the full content

of their digital camera disks by radio to the offices at the main

press center. The first pictures reached newspapers around the

world in less than 10 minutes after the finish of the race, and

Australian papers were in print 40 minutes later.

Hundreds

of 400 to 1200mm long lenses faced the finish line, many more

followed the runners from their starting blocks from both sides

along the 100-meter track. When the winners ran their lap of honor,

agency and Australian newspaper photographers were handling their

laptops while in their positions, and transmitted selective pictures

on standby ISDN lines. Others simply transmitted the full content

of their digital camera disks by radio to the offices at the main

press center. The first pictures reached newspapers around the

world in less than 10 minutes after the finish of the race, and

Australian papers were in print 40 minutes later.  Another

key to success seemed to be the selection of photo venue chiefs

and their staff, the people assigned to assist (and control) photographers

on-site. Kemper selected them in coordination with the Sydney

newspaper and agency photo editors. Most of the venue photo managers

are experienced photo editors and photographers themselves, like

Paul Matthews, the venue manager of the main Olympic stadium,

who is a former Sydney Morning Herald photographer, and Peter

Charles, who was at the Aquatic stadium and came as photographer

and editor from the Melbourne Age. "The venue managers have been

terrific, they really understand us," said Julian Zakaras of News

Limited. Word was out to be helpful, first of all, and keep order

second. Ronald Kubik, a journalist from Apia, Samoa, could not

believe his luck when a volunteer helped him to get right up to

the boxing ring - a "Pool Only" position - to take a picture of

a Samoan boxer. "I got a real boxing picture with my snapshot

camera," he said, "but I must admit I got better pictures from

the IOPP later on."

Another

key to success seemed to be the selection of photo venue chiefs

and their staff, the people assigned to assist (and control) photographers

on-site. Kemper selected them in coordination with the Sydney

newspaper and agency photo editors. Most of the venue photo managers

are experienced photo editors and photographers themselves, like

Paul Matthews, the venue manager of the main Olympic stadium,

who is a former Sydney Morning Herald photographer, and Peter

Charles, who was at the Aquatic stadium and came as photographer

and editor from the Melbourne Age. "The venue managers have been

terrific, they really understand us," said Julian Zakaras of News

Limited. Word was out to be helpful, first of all, and keep order

second. Ronald Kubik, a journalist from Apia, Samoa, could not

believe his luck when a volunteer helped him to get right up to

the boxing ring - a "Pool Only" position - to take a picture of

a Samoan boxer. "I got a real boxing picture with my snapshot

camera," he said, "but I must admit I got better pictures from

the IOPP later on."