|

|

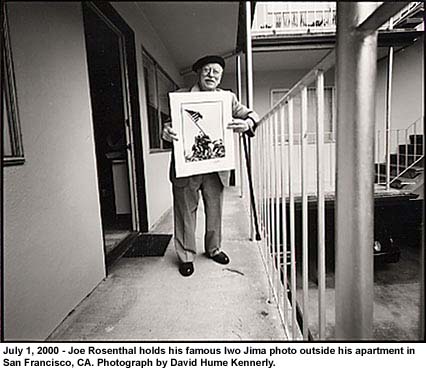

(Last June, I began work on a story about photographers over 80, which was published in the January 2001 issue of Vanity Fair. After a phone conversation with photographer Joe Rosenthal, I wrote down these thoughts, which appear here, belatedly.) This week Flags of Our Fathers hit number one on The New York Times Non fiction best-seller list. Imagine it: an entire book about a single photograph. A picture, taken at 1/400th of a second--in 1945--is now worth 160,000 words. Flags of Our Fathers, by James Bradley and Ron Powers (published by Bantam), explores the lives and times of half a dozen GIs, veterans of the Pacific theater in World War II. The men were not picked randomly; one of them, it so happens, is author Bradley's father, a wartime medic named John "Doc" Bradley. Of more significance, though, is the fact that the six were the very men whom fate had ushered into the famous frame depicting the raising of the flag on the summit at Iwo Jima's Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945. The photo has become an icon. Along with a handful of images, it is an incomparable symbol of wartime valor.

But not a word of the book would exist were it not for the vision and talent of one man: Joe Rosenthal, the Associated Press photographer who made the picture. On a couple of occasions, I've huddled with Joe on a crisp fall afternoon at the annual gathering of photojournalism's legends--and young aspirants--at the Eddie Adams Workshop in rural Liberty, New York. As I recall, Joe always had a gleam in his eye, and a shy grin which he would hide beneath his clipped, gray moustache. He looked dapper in his signature beret. He delighted in the camaraderie of like-minded photojournalists at the workshop, men such as Hilmar Pabel and Carl Mydans, combat photographers who had also covered the second World War from the front lines. If the best-seller list had been kind enough to anoint a book about a photograph, it must have also sparked some joy in the life of that picture's creator. I called Joe at his home in San Francisco. We spoke about old friends and his old beret. He told me he still kept it close at hand: "It's by the door right here." But what, I wondered, did he think of the Bradley-Powers book? He cleared his throat and said, "I haven't seen it." He quickly added, "I hear they've done a great job. But I haven't managed to get out [of the apartment] to the store." Hadn't anyone sent a copy along? A publicist? A colleague? "I haven't seen it. I've read a couple of reviews, some articles about it." I told him I'd be sure to send him the book the next morning. (When I placed a followup call the next week, he mentioned that he had received it and that his daughter had also brought him a copy--an audio version, I believe. After pointing out two flaws in the book, he seemed uncomfortable commenting about it any further. He wanted to read the entire volume first.) It is remarkable that the picture, which won the Pulitzer Prize, ever materialized in the first place. The hoisting of the flag occurred in the span of only four seconds. ("I swung my camera around," Rosenthal is quoted as saying in Flags of Our Fathers, "and held it until I could guess that this was the peak of the action, and shot. I couldn't positively say I had the picture. It's something like shooting a football play; you don't brag until it's developed.") Next, the roll of film went through a bruising gauntlet. Sunlight had leaked into Rosenthal's camera as he made his 12 exposures that day. ("Two were ruined" by the light leaks, according to the book. "Those two were adjacent to the [critical] tenth frame.") In fact, Rosenthal used sheet film, so the co-authors' use of the term 'frame' is inaccurate. Then, write Bradley and Powers, "It was tossed into a mail plane headed for the base at Guam, a thousand miles south across the Pacific. There the film would pass through many hands, any of which could consign it to the wastebasket. Technicians from a 'pool' lab would develop it. Their mistakes were routinely tossed aside. Then censors would scrutinize it; and finally the 'pool' chief would look at each print to decide which was worth transmitting back to the United States via radiophoto." At last, Rosenthal's photograph passed before a fateful pair of eyes. "On a routine night in his bureau office, John Bodkin, the AP photo editor in Guam casually picked up a glossy print. He looked at it. He paused, shook his head in wonder, and whistled. 'Here's one for all time!' he exclaimed to the bureau at large. Then, without wasting another second, he radiophotoed the image to AP headquarters in New York at 7a.m. Eastern War Time. Soon afterward, wirephoto machines in newsrooms across the country were picking up the AP image. Newspaper editors, accustomed to sorting through endless battle photographs, would cast an idle glance at it, then stand fascinated. 'Lead photo, page one, above the fold,' they would bark." Thousands have now read Flags of Our Fathers. If you are one of them, you might be moved to send a note to its authors, James Bradley and Ron Powers, the latter a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist himself, in care of Bantam Books (1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036). But perhaps you'd prefer to send a note of thanks to Joe Rosenthal (in care of the Associated Press, 50 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, New York 10020). It's his picture, after all. Rosenthal is 89. The photograph is 55.

|

Bradley

and Powers' earnest, dutiful narrative is part memoir, part journalism,

part social history. Its power, like that of a vintage wine, derives

from its accumulation, over time, of increments of subtle detail

and texture.

Bradley

and Powers' earnest, dutiful narrative is part memoir, part journalism,

part social history. Its power, like that of a vintage wine, derives

from its accumulation, over time, of increments of subtle detail

and texture.