|

ROBERT

PLEDGE, co-founder and director of the photo agency Contact

Press Images (New York, Paris), is a champion of photojournalism.

DAVID FRIEND: This year, you went to Holland and chaired the

jury of World Press Photo, considered the most prestigious international

award for photojournalism. Though few of us get to see AIDS

coverage in our daily news diet, I’m sure you pored over

many images concerning AIDS in Africa, much of it unpublished.

ROBERT PLEDGE: That's true. There were almost 4,000 photographers

and 43,000 images this year at the World Press Photo competition.

Amongst the entries, three or four subjects of news value were

prominent. There was the situation in Chechnya, mainly by Russian

photographers. Very good work, actually. There was an abundance

of material on the Intifada, which began to flare up last year.

Quite a fair amount of work from Sierra Leone and the terrible

carnage over there: Adults, children, the elderly with hands

and legs and arms cut off. And there was AIDS. AIDS in Southern

Africa, Zambia, Malawi, South Africa. All of a sudden, AIDS

is on the same level as these various wars taking place in Africa,

in the Middle East, in the former Soviet Union.

FRIEND: Did it seem to you that the story was suddenly drawing

the attention of concerned photographers?

PLEDGE:

Actually, when you know who the photographers are working on

the subject today, many of them are veterans from the wars of

the '70s, '80s or '90s. Jim Nachtwey, and even more recently,

Don McCullin, all these photojournalists -- agency photojournalists,

news magazine photojournalists -- who produced this kind of

work. So that's interesting, because until recently, none of

this existed. I mean, for the longest time, nobody paid much

attention to AIDS in Southern Africa. A few years ago, Gideon

Mendel won the Canon Photo Essay Award and the W. Eugene Smith

Grant. But that work was produced in a totally different era.

The monies came from foundations or grants, and not from magazines.

This year it's quite different. So yes, I would be tempted to

say that AIDS in Africa has become not trendy and not fashionable,

but certainly somewhat. . . PLEDGE:

Actually, when you know who the photographers are working on

the subject today, many of them are veterans from the wars of

the '70s, '80s or '90s. Jim Nachtwey, and even more recently,

Don McCullin, all these photojournalists -- agency photojournalists,

news magazine photojournalists -- who produced this kind of

work. So that's interesting, because until recently, none of

this existed. I mean, for the longest time, nobody paid much

attention to AIDS in Southern Africa. A few years ago, Gideon

Mendel won the Canon Photo Essay Award and the W. Eugene Smith

Grant. But that work was produced in a totally different era.

The monies came from foundations or grants, and not from magazines.

This year it's quite different. So yes, I would be tempted to

say that AIDS in Africa has become not trendy and not fashionable,

but certainly somewhat. . .

FRIEND: . . .a la mode, as cynics might say?

PLEDGE: A la mode, yes. In some ways, yes. All of a sudden.

All of a sudden. Maybe because there were no dominant wars anywhere

else in the world during the whole year that went by, as opposed

to, in previous years, when Kosovo or Bosnia occupied the front

pages and the energies of photojournalists throughout the year.

Or even the whole Rwanda-Zaire crisis.

FRIEND: Absolutely.

PLEDGE: So there's the difference. The year is more splintered.

There are several items that are sort of exotic, if you will,

that capture the attention, and AIDS in Africa has become that.

There's something positive about that. I am pleased that attention

is finally given to an issue that is a major issue. It's paramount.

FRIEND: But are magazines publishing this work? At one point

you said that there's this abundance of strong imagery but too

few places to...

PLEDGE: Well, certainly, there's very little published in relation

to the enormity of the situation and the depth. There has been

more published, I guess, in the last year than there had been

previously, so there is a bit of progress. It's true that it's

also been spoken about more, and there's been this whole controversy

in South Africa, the situation with President Thabo Mbeki not

recognizing HIV as the main cause of AIDS, and other controversies.

So it's been made more newsworthy. And because, to some extent,

in the Western World - - Europe and the United States - - there

has been a perception of a slowing-down of the spread of AIDS

in the last few years, I think the attention is now going to

those countries that are seeing the growth or the development

of the disease increase dramatically. In Africa...In China…

FRIEND: Or Russia, certainly.

PLEDGE: Russia quite a bit, and India even more so, are seriously

affected. But Africa, it's just taken on incredible proportions.

"Taken on," not really, because actually we've known

about AIDS in Africa for ages. It may have even started there.

But it has been able to spread faster because of less medical

attention, because of different lifestyles, because of many

reasons, some of which are not very clear even to researchers.

FRIEND: So today, there may be more photographers who are embracing

this subject. But let me take you back 20 years. Back to ’81

or ’82. Your agency, Contact, had been formed in 1976,

but by ’81 and ’82, very few photographers thought

to cover this subject. Yet Contact did.

PLEDGE:

We were five years old when it first became known. Actually

I would say we started off in the business -- the first five

years, the formative ones, the most important ones -- with two

dominant themes, I guess. One was human rights and the issues

related to it, especially in '76, in the aftermath of Vietnam

and Chile and various other events. And the other was AIDS,

I think. It became a major, major, major item that we sort of

discovered in 1981. Recently, I was looking through the index

of subjects that we have worked on. That usually indicates when

the interest started developing. And I saw that the first thing

we ever did was in the U.S.A. -- AIDS in Veterans Hospital in

New York City in November 1981, by Alon Reininger. Through Alon,

Contact was at the forefront of AIDS coverage from the earliest

stages. We were amongst the very first, and maybe the first

people, or amongst the few in the journalistic community who

had interest in this strange phenomenon. "In the forefront"

would imply that we were sort of activists and militants, and

we were… PLEDGE:

We were five years old when it first became known. Actually

I would say we started off in the business -- the first five

years, the formative ones, the most important ones -- with two

dominant themes, I guess. One was human rights and the issues

related to it, especially in '76, in the aftermath of Vietnam

and Chile and various other events. And the other was AIDS,

I think. It became a major, major, major item that we sort of

discovered in 1981. Recently, I was looking through the index

of subjects that we have worked on. That usually indicates when

the interest started developing. And I saw that the first thing

we ever did was in the U.S.A. -- AIDS in Veterans Hospital in

New York City in November 1981, by Alon Reininger. Through Alon,

Contact was at the forefront of AIDS coverage from the earliest

stages. We were amongst the very first, and maybe the first

people, or amongst the few in the journalistic community who

had interest in this strange phenomenon. "In the forefront"

would imply that we were sort of activists and militants, and

we were…

FRIEND: I understand what you mean, the distinction.

PLEDGE: Yes. But we were there, and totally bewildered, puzzled

by this thing. We were reading these short pieces in The

New York Times. The word AIDS wasn't even used. I mean,

it was this strange cancer that was devouring the gay community...

It was quite mysterious. And because it was mysterious, we were

intrigued. And Reininger is somebody who the more mysterious

it is, the more he's intrigued, the more he digs into it. And

it does happen that through his wife, Shura, he spent a lot

of time with Larry Kramer, the playwright who was extremely

aware of what was happening within the gay community in the

States - - in New York in particular, where there was this disease

that was having drastic, devastating consequences. From then

on, Alon did a lot. In 1982, we primarily did research and tried

to figure out what this was about. It was very difficult. The

access was almost nil; we couldn't get anywhere.

One day Alon was to meet a patient who had accepted to be photographed,

and thought it was even important that he be photographed because

he wanted to make the general public aware of how wicked this

disease was. So Alon went to his home that evening to meet him.

The door was open. He was told to wait a little bit, that he

was being prepared. And then he was told that he could go into

the room and meet the person. When he walked in, he realized

the man was dead. Died in front of him, the minute he walked

into the room. The disease was so far along. So Alon saw death

at first. And he had seen people die in Central America and

Southern Africa or the Middle East, but right there in the bedroom

and in such a devastating way.

FRIEND: Alon had quite a bit of influence on Contact’s

other photographers, didn’t he?

PLEDGE: Well, he had a lot of impact because this was a very

small group and we were really in that tradition of the early

days of Magnum, and we'd get together all the time and speak

and exchange - - e-mail didn't exist. And he sort of, yes, contaminated…

FRIEND: I love that. He contaminated...

PLEDGE: Right.

FRIEND: Encouraged them.

PLEDGE: And got everybody, absolutely. I remember one day, I

guess it was maybe in '82 or '83, walking down the street and

bumping into a senior editor of Time magazine who knew

that we were often ahead of the pack in terms of working on

stories that would be in the news in the relatively near future.

And he said to me, "So what's our next big story?"

I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "Well, what's

our next big story? What should we expect at Time out

of you guys?" And I said, "AIDS." And he said,

"What?" I said, "Yes, AIDS." He said, "What

is that?" I said, "It's this disease, a mysterious

disease," and then I tried to explain it to him, and he

had no idea what I was speaking about. "Isn't that strange?

I think I would have heard something." I said, "No-no,

this is... Within the year, this will be a cover story."

So he called me up a couple of days later, and said, "You

know, I checked it out here. Nobody knows what you're speaking

about." I said... I was stunned. He said he even asked

the science editor, who didn't know anything about it. So a

few months later, it really started hitting. That must have

been in '82, very early on. But I don't think Time did

a major story until '83.

Alon's

impact was quite tremendous. [Another Contact photographer]

Frank Fournier worked on various aspects here in New York City,

did a big story for New York magazine, then a major story

- - 8-10 pages - - for Stern magazine. Dilip Mehta got

involved and photographed Ryan White early on, for Picture

Week, which was [in its trial stages at] Time, Inc. Jane

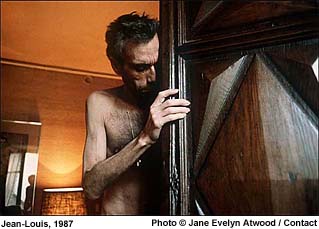

Evelyn Atwood, in Paris, whom I had known for a number of years,

and who liked and respected Alon a lot, was sort of totally

intrigued. She got involved in the story, focusing on Jean-Louis,

a French television producer. He probably has a last name, but

we called him "Jean-Louis," by his first name. And

she really lived with this man for four and a half months, from

the time she met him to the time he died. And that was published

in Paris Match and in Stern magaznine, Sette

magazine, and in other major publications. And basically,

it is primarily in Europe, nothing in the USA. Alon's

impact was quite tremendous. [Another Contact photographer]

Frank Fournier worked on various aspects here in New York City,

did a big story for New York magazine, then a major story

- - 8-10 pages - - for Stern magazine. Dilip Mehta got

involved and photographed Ryan White early on, for Picture

Week, which was [in its trial stages at] Time, Inc. Jane

Evelyn Atwood, in Paris, whom I had known for a number of years,

and who liked and respected Alon a lot, was sort of totally

intrigued. She got involved in the story, focusing on Jean-Louis,

a French television producer. He probably has a last name, but

we called him "Jean-Louis," by his first name. And

she really lived with this man for four and a half months, from

the time she met him to the time he died. And that was published

in Paris Match and in Stern magaznine, Sette

magazine, and in other major publications. And basically,

it is primarily in Europe, nothing in the USA.

FRIEND: Europe.

PLEDGE: …that we got the attention. We published with greater

difficulty in the United States. Although newspapers started

picking up on it. I remember I was at a workshop at Lake Tahoe.

I'm not even sure who was organizing it. Wherever I would go,

a workshop, when I was on a panel, or whatever, I'd always have

a slide tray and a presentation and something to say about AIDS

- - I had become a bit of an activist - - and spoke a lot about

it all those early years, especially to younger photographers.

I remember that each time it did have an impact. Shortly after

that, people would get involved in projects related to it. I

remember one photographer in particular, whose name I cannot

remember, who was working for the San Jose Mercury News.

She asked to take a year off to work on the issue of AIDS in

America, as a result of this workshop that I attended and where

I showed Alon’s work. So directly or indirectly, whether

he was speaking about it or not, certainly Alon made an impact

on many people.

FRIEND: So the ripples were felt, particularly in the photo

community.

PLEDGE: Yeah. And I think we were all very concerned, because

we realized the depth of the prejudice, the ignorance, the lack

of information and understanding about the disease. And we knew

very early on that it was not a gay disease; it was a disease

that was a devastating disease that did hit the gay community

more specifically in the United States.

FRIEND: Am I wrong, or did you at one point represent Maggie

Steiber, the photographer who was in Haiti a lot?…

PLEDGE: No, she was a good friend, and she met Alon Reininger

in South Africa, and there was a connection. Yes. But speaking

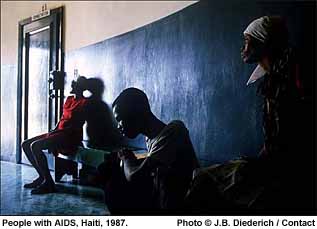

of Haiti, people like J.B. Diederich worked extensively in Haiti

and...

FRIEND: And he was one of your photographers at the time?

PLEDGE:

Yes. He gave up photography for television later on. But that

was one of the main things he did, worked on Haiti, and because

of….Well, definitely because of Alon. There's no question

about that. Because he sort of admired Alon tremendously. And

other photographers, [Carlos Humberto] T.D.C. and so on and

so forth... We started getting less involved in covering on

a regular basis the issues and the aspects of the disease and

its spread because by then, by the late '80s, people finally

got into looking more seriously at all these issues and aspects,

so we didn't feel that there was as much of a need for us... PLEDGE:

Yes. He gave up photography for television later on. But that

was one of the main things he did, worked on Haiti, and because

of….Well, definitely because of Alon. There's no question

about that. Because he sort of admired Alon tremendously. And

other photographers, [Carlos Humberto] T.D.C. and so on and

so forth... We started getting less involved in covering on

a regular basis the issues and the aspects of the disease and

its spread because by then, by the late '80s, people finally

got into looking more seriously at all these issues and aspects,

so we didn't feel that there was as much of a need for us...

FRIEND: I thought Frank Fournier was breaking ground in Romania,

though.

PLEDGE: Frank and even Alon pursued it whenever they were in

a situation where it made sense, in particular Romania, where

Frank did quite a bit of work on the children who were affected

because of medical and political reasons. Then Alon was really

interested in Africa. He knew and always said that Africa was

the place to go to, and he spent quite a bit of time in '92-'93

working in Zambia and southern Africa and Malawi, producing

interesting imagery, although people were not always forthcoming

and the authorities were not doing anything to make it easy

to work. But he came back with some very strong color photographs.

He worked in color, thinking that maybe now it could be more

mainstream and reach more magazines - - and we got absolutely

nowhere. He tried grants, and we got nowhere. Maybe a couple

of years later, Gideon Mendel, who is with Network, finally

broke through. But I mean, in the grant world, and not in the

newspaper and magazine world - - although The Independent

(in London), with Colin Jacobson, did initially give him some

support. And Colin had done so because he had been also sort

of brainwashed by Alon early-on, and was one of our allies in

this field. Then other people with whom we’re associated,

like Nick Danziger, who is a writer-photographer-filmmaker,

has been, in the last couple of years, working in Russia and

in southern Africa for British publications. And more recently,

Don McCullin has been working in South Africa and Zambia; Don

has often spoken about the issue with Alon, whom he likes and

respects. And also a younger photographer, Kristen Ashburn,

has been working in Zimbabwe.

FRIEND: You have David Binder, who...

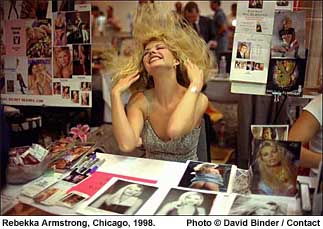

PLEDGE:

…who has been working on this very specific case of a former

Playboy bunny with AIDS. He also did early work on the subject.

And so did Lori Grinker. Annie Leibovitz has been involved in

different ways. I remember a number of years ago James Danziger

organized this project, this book inviting photographers to

participate by donating their work for the purpose of a donation

for research, and Annie was the first one to accept. And it's

because she did that, that James Danziger has been able to push

his project forward. Annie has been very interested and involved

in a very discreet way in this issue by contributing, and taking

for Vanity Fair and other publications, some photographs

related to events or people involved in the AIDS crusade or

issue. Everybody here has done, at some stage, something. Ken

Jarecke, Gary Matoso, Jean-Claude Coutausse. Tomas Muscionico.

David Burnett photographed Mathilde Krim, Magic Johnson. He

shot a Time magazine cover on Robert Gallo and AIDS research,

etc. PLEDGE:

…who has been working on this very specific case of a former

Playboy bunny with AIDS. He also did early work on the subject.

And so did Lori Grinker. Annie Leibovitz has been involved in

different ways. I remember a number of years ago James Danziger

organized this project, this book inviting photographers to

participate by donating their work for the purpose of a donation

for research, and Annie was the first one to accept. And it's

because she did that, that James Danziger has been able to push

his project forward. Annie has been very interested and involved

in a very discreet way in this issue by contributing, and taking

for Vanity Fair and other publications, some photographs

related to events or people involved in the AIDS crusade or

issue. Everybody here has done, at some stage, something. Ken

Jarecke, Gary Matoso, Jean-Claude Coutausse. Tomas Muscionico.

David Burnett photographed Mathilde Krim, Magic Johnson. He

shot a Time magazine cover on Robert Gallo and AIDS research,

etc.

FRIEND: So after human rights, AIDS became a second front for

you all.

PLEDGE: A second front, or, in a way just a continuation. Because

what I think also intrigued us about AIDS was maybe less even

the medical aspect than the bigotry, the forms of racism it

took. I mean, the human rights...

FRIEND: So how it related to human rights.

PLEDGE: Absolutely.

FRIEND: Absolutely. That's clear.

PLEDGE: The intolerance. So for us, in a way, it was sort of

a continuation of kinds of issues that we have always been interested

in.

Visit

the UNAIDS website:

|