|

GIDEON MENDEL,

a London-based South African photojournalist, received the 1996 W. Eugene

Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography for his work exploring the lives

of people with AIDS. An exhibition that will include Mendel’s images

will be shown in the gallery of the United Nations, in New York, during

the U.N. Special Session on AIDS in mid June:

In 1993, I was part of a group project called “Positive Lives,”

organized by my photo agency, Network, in which photographers responded

to AIDS in the U.K. My first exposure to the issue was photographing

in an AIDS ward in London. I found the situation different than any

I’d ever experienced as a photojournalist. It was only 10 percent

photography and 90 percent communication and connection with people,

dealing with issues of confidentiality, considering how people should

be projected, being sensitive not to portray people as victims. That

same year, I made contact with a mission hospital in Zimbabwe and I

photographed there.

I felt that as an African photographer I needed to find a way to respond

to the AIDS crisis which was clearly developing in Africa at that time.

So that essay, looking at one remote hospital in an area where more

than 25 percent of pregnant women were testing HIV-positive, was the

beginning of my work on HIV and AIDS in Africa.

While I was there I was photographing a patient whose wife was lifting

him up in his bed. As I was documenting that scene, he had a sudden

seizure and died from kidney failure. On my contact sheet I can follow

the sequence as he moves from life to death. These are images I have

mixed feelings about: as a news photographer I have photographed many

dead people, yet there is something about my role in that situation

I do not feel comfortable with. Are there some moments which should

be sacrosanct, exempt from the intrusion of a camera? In that situation,

seconds after the man had died, and the reality of the situation began

to strike me, his family began to wail and break down. I put my camera

down and stopped photographing. The doctor who had been called looked

at me calmly and said, “Come on man, do your job.” In that

context of medical crisis it was the only constructive thing I knew

how to do.

Since then, I’ve stuck with the issue and over the last nine years

I have worked in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi, South Africa and

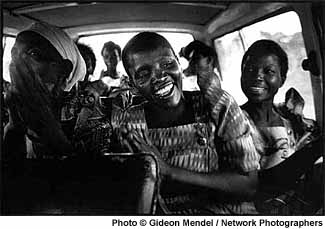

Uganda. But in many ways my attitude has matured and evolved. Initially,

I approached it in a very direct, photojournalistic way, looking to

make strong images. When people are dying from AIDS, they’re skeletal.

Visually, it is often a very extreme and dramatic situation. But by

working on this issue over the years, I have found I’ve really

had to challenge myself and my way of approaching the subject. I’m

much more concerned about portraying people in a more positive, individualized

way. I have also chosen to keep on returning to some communities that

I have photographed in, sort of digging a deeper hole, getting more

connected to a few communities, rather than having wider geographical

coverage.

For

example, I’m proudest of a story I did this past year on one person,

Mzokonah Malevu, a person with AIDS in South Africa. I think I achieved

real depth. I began to photograph him in April of 2000. And I went back

to visit him and his family on four different occasions over the year,

leading up to attending his funeral in December. I made a strong, personal

connection with him and his family, who were taking care of him with

amazing love within the context of extreme poverty. Mzokonah was living

in a three-room squattershack with 21 people. He was open and out about

his disease. He had decided that he wanted his funeral to be an AIDS-education

event and he made me promise that when he died I would come and take

photographs at his funeral. He wanted to tell his story to the world

and I was a sort of conduit for him to do it. The quotes which I collected

from him, together with the images which tell his story from life to

death, make a powerful, personalized statement. For

example, I’m proudest of a story I did this past year on one person,

Mzokonah Malevu, a person with AIDS in South Africa. I think I achieved

real depth. I began to photograph him in April of 2000. And I went back

to visit him and his family on four different occasions over the year,

leading up to attending his funeral in December. I made a strong, personal

connection with him and his family, who were taking care of him with

amazing love within the context of extreme poverty. Mzokonah was living

in a three-room squattershack with 21 people. He was open and out about

his disease. He had decided that he wanted his funeral to be an AIDS-education

event and he made me promise that when he died I would come and take

photographs at his funeral. He wanted to tell his story to the world

and I was a sort of conduit for him to do it. The quotes which I collected

from him, together with the images which tell his story from life to

death, make a powerful, personalized statement.

In

the same way, I’ve spent time in Uganda recently with a very inspirational

priest, Reverend Gideon Byamugisha, who may be the only openly HIV-positive

priest in Africa. He does a lot of educational work and campaigning

about AIDS. I also photographed a wonderful woman called Florence. She’s

positive and is quite ill. Her husband died. Their two co-wives died

(polygamy is practiced in the area) and she ended up looking after eight

of her own children and six of the children of the co-wives. She decided

to come out and challenge the stigma in the community that is attached

to AIDS. She actually began a successful, mainly female organization

in the area who are all positive. They’ve produced their own songs

and a drama program to educate their community and others. They generate

income through raising chickens, making bricks and grass mats. Small

things, but they all kind of work together and help each other. I like

telling those kinds of small, positive stories. In

the same way, I’ve spent time in Uganda recently with a very inspirational

priest, Reverend Gideon Byamugisha, who may be the only openly HIV-positive

priest in Africa. He does a lot of educational work and campaigning

about AIDS. I also photographed a wonderful woman called Florence. She’s

positive and is quite ill. Her husband died. Their two co-wives died

(polygamy is practiced in the area) and she ended up looking after eight

of her own children and six of the children of the co-wives. She decided

to come out and challenge the stigma in the community that is attached

to AIDS. She actually began a successful, mainly female organization

in the area who are all positive. They’ve produced their own songs

and a drama program to educate their community and others. They generate

income through raising chickens, making bricks and grass mats. Small

things, but they all kind of work together and help each other. I like

telling those kinds of small, positive stories.

I’ve also come to feel that images aren’t enough to express

the story of AIDS. What I’ve found very effective is combining

visuals with personal quotes from the people I’m photographing

to give them a voice alongside their image. I’ve used this approach

in exhibitions, on the website (www.networkphotographers.com/aidsinafrica)

and in a book I’m publishing this fall called A Broken Landscape:

HIV and AIDS in Africa (supported by Action Aid, a charity involved

in many AIDS- and poverty-alleviation projects in Africa). It has also

become a priority for me that my work be used and seen in the countries

where the photographs have been taken. I am currently working with Action

Aid to produce a series of 20 educational posters using my images and

the quotes I have collected from my subjects. These will hopefully be

widely distributed in Africa.

There is a real danger when photographers approach AIDS in a gratuitous

way because the ramifications are potentially so extreme. For me, it’s

kind of walking a tightrope. I have made some photographs that show

the horror. But it’s important not just to show people dying but

to show that there are 30 million people living with AIDS in Africa.

Many medical people I’ve encountered en route relate the experience

that people with AIDS who live positively actually live longer and have

more productive lives than those who are in denial. For 99.9 percent

of people in Africa, for whom drugs are not available, living positively

is really important.

I’ve been working on this subject for a long time. Obviously, this

was one of the biggest issues in the world. But at many points along

the road, I felt almost like I’ve been going crazy. It was a really

frustrating experience for a long time. Like I’d been banging on

the doors but no one seemed to want to know. It was incredibly difficult

to get any magazine to even want to look at my pictures let alone publish

them. Then there was some kind of sea-change last year with the outgoing

president, Bill Clinton, making strong statements on the issue of AIDS

in Africa, and the effect of the International AIDS Conference, in Durban.

There is now much more interest in my work.

Photographs can be powerful weapons. They can convey intimacy, tragedy,

passion and hope. I do not consider myself an objective photographer.

I see my work on AIDS in Africa as partisan and committed to social

issues. I hope that my images address the pain and suffering caused

by the disease yet at the same time work to challenge the stereotype

of people with AIDS in Africa as pathetic victims. In Africa, as in

the West, people with AIDS are starting to come together to mobilize

against the predjudices they often face, to help their own communities

fight against the virus, to demand equal access to new drug treatments.

As a photojournalist it is all too easy to be drawn to horror. It is

much harder to photograph hope. In order to properly address this issue,

I feel that it is important to do both well.

Visit

this website:

|

For

example, I’m proudest of a story I did this past year on one person,

Mzokonah Malevu, a person with AIDS in South Africa. I think I achieved

real depth. I began to photograph him in April of 2000. And I went back

to visit him and his family on four different occasions over the year,

leading up to attending his funeral in December. I made a strong, personal

connection with him and his family, who were taking care of him with

amazing love within the context of extreme poverty. Mzokonah was living

in a three-room squattershack with 21 people. He was open and out about

his disease. He had decided that he wanted his funeral to be an AIDS-education

event and he made me promise that when he died I would come and take

photographs at his funeral. He wanted to tell his story to the world

and I was a sort of conduit for him to do it. The quotes which I collected

from him, together with the images which tell his story from life to

death, make a powerful, personalized statement.

For

example, I’m proudest of a story I did this past year on one person,

Mzokonah Malevu, a person with AIDS in South Africa. I think I achieved

real depth. I began to photograph him in April of 2000. And I went back

to visit him and his family on four different occasions over the year,

leading up to attending his funeral in December. I made a strong, personal

connection with him and his family, who were taking care of him with

amazing love within the context of extreme poverty. Mzokonah was living

in a three-room squattershack with 21 people. He was open and out about

his disease. He had decided that he wanted his funeral to be an AIDS-education

event and he made me promise that when he died I would come and take

photographs at his funeral. He wanted to tell his story to the world

and I was a sort of conduit for him to do it. The quotes which I collected

from him, together with the images which tell his story from life to

death, make a powerful, personalized statement. In

the same way, I’ve spent time in Uganda recently with a very inspirational

priest, Reverend Gideon Byamugisha, who may be the only openly HIV-positive

priest in Africa. He does a lot of educational work and campaigning

about AIDS. I also photographed a wonderful woman called Florence. She’s

positive and is quite ill. Her husband died. Their two co-wives died

(polygamy is practiced in the area) and she ended up looking after eight

of her own children and six of the children of the co-wives. She decided

to come out and challenge the stigma in the community that is attached

to AIDS. She actually began a successful, mainly female organization

in the area who are all positive. They’ve produced their own songs

and a drama program to educate their community and others. They generate

income through raising chickens, making bricks and grass mats. Small

things, but they all kind of work together and help each other. I like

telling those kinds of small, positive stories.

In

the same way, I’ve spent time in Uganda recently with a very inspirational

priest, Reverend Gideon Byamugisha, who may be the only openly HIV-positive

priest in Africa. He does a lot of educational work and campaigning

about AIDS. I also photographed a wonderful woman called Florence. She’s

positive and is quite ill. Her husband died. Their two co-wives died

(polygamy is practiced in the area) and she ended up looking after eight

of her own children and six of the children of the co-wives. She decided

to come out and challenge the stigma in the community that is attached

to AIDS. She actually began a successful, mainly female organization

in the area who are all positive. They’ve produced their own songs

and a drama program to educate their community and others. They generate

income through raising chickens, making bricks and grass mats. Small

things, but they all kind of work together and help each other. I like

telling those kinds of small, positive stories.