|

"WHEREVER YOU GO, WE GO"

A look at "The Stars and Stripes"

By Marianne Fulton

"Stars and Stripes "has been one of America's great newspapers

for over fifty years. Within its pages the work of excellent writers,

beloved cartoonists and some of the best combat photographers have appeared.

Yet, it is little known to the contemporary public at large. It is an

army publication whose mission and success has been to be there, as

its self- advertisement says, "Wherever you go, we go." It

has followed soldiers through Germany, Japan, Korea and Vietnam to name

a few dominant areas. It is still with them in these places and many

others.

The

name itself has a journalistic history: in short, during the Civil War

there were at least four different editions of "The Stars and Stripes."

The basic tenets for the military newspaper were set in Paris during

World War I, according to Ken Zumwalt in his book, "The Stars and

Stripes: World War II and the Early Years", (1989). The first military

newspaper was published at Bloomfield, Missouri, on November 9, 1861

for the soldiers of the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteer Regiments.

In 1917, the American Expeditionary Force landed in France under the

command of General John Pershing. Pershing authorized a newspaper to

be "written by soldiers for soldiers" He went on to declare

that it should be free of censorship by field commanders [from: www.stripes.com].

"The Stars and Stripes" of this era published 7I weekly issues,

from February 8, 1918 - June 13, 1919. The

name itself has a journalistic history: in short, during the Civil War

there were at least four different editions of "The Stars and Stripes."

The basic tenets for the military newspaper were set in Paris during

World War I, according to Ken Zumwalt in his book, "The Stars and

Stripes: World War II and the Early Years", (1989). The first military

newspaper was published at Bloomfield, Missouri, on November 9, 1861

for the soldiers of the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteer Regiments.

In 1917, the American Expeditionary Force landed in France under the

command of General John Pershing. Pershing authorized a newspaper to

be "written by soldiers for soldiers" He went on to declare

that it should be free of censorship by field commanders [from: www.stripes.com].

"The Stars and Stripes" of this era published 7I weekly issues,

from February 8, 1918 - June 13, 1919.

The start of what would be called the "European" edition was

published weekly in London, England for American troops in Ireland,

April 18, 1942. Gen. George C. Marshall, the army chief of staff, repeated

Gen. Pershing's direction that the newspaper was by and for soldiers.

He went on to write in that first edition, "A soldier's newspaper,

in these grave times, is more that a moral venture. It is a symbol of

the things we are fighting to preserve and spread in this threatened

world. It represents the free thought and free expression of a free

people" (Zumwalt, p. 6) The "Pacific" edition would begin

October 3, 1945.

There were never

many photographers working for “The Stars and Stripes.” The

paper got a lot of their pictures from the photographic divisions of

the military, plus the wire services. Many “Stars and Stripes”

reporters carried cameras. However, the few photographers who did work

full time for the paper were among the greats.

The photographers working for "The Stars and Stripes" were

there to get the job done, to cover wars, peace and a Cold War and to

get the information to the soldiers wherever they were. The photographers'

work was (and is) an expression of their interaction with the world,

their engagement with history and daily living. They looked for the

essence of the situation and through the pages of "The Stars and

Stripes" (S&S) distributed their stories to their public.

Among this Band of Brothers were... SLIM AARONS

George

"Slim" Aarons began as the official photographer at West Point

in the early 1940s. There he met the movie director Frank Capra, who

during those years was working on movies for the army and charged with

setting up the magazine "Yank." This new weekly magazine was

to come out with the newspaper, S&S. George

"Slim" Aarons began as the official photographer at West Point

in the early 1940s. There he met the movie director Frank Capra, who

during those years was working on movies for the army and charged with

setting up the magazine "Yank." This new weekly magazine was

to come out with the newspaper, S&S.

Capra wanted Aarons to work on "Yank" but the Army would not

let any soldier out of West Point unless they were going overseas. When

Capra was made a major in the Signal Corps, he convinced the army to

let Aarons work for him on the magazine. Soon Slim Aarons was on his

way to London.

"Our assignment was to go to London and check in with 'Stars and

Stripes' because they had an office there already--Andy Rooney was there.

Once in the office he and others heard their basic order: "'Now

fellas, when you are lying in that foxhole and all the firing is going

on, I want you to remember ...Get that story!’ We were aghast,

but he was a Colonel, so we didn't show it.”

"We were in the VIP category, because we had to get there quickly….

That was how powerful General Marshall was. Our orders said 'You will

not interfere with these people. This is a general order they will be

doing their job which is to take photographs and stories for 'Yank'

magazine and 'Stars and Stripes.'” Later, when the Germans were

at the Gates of Alexandria, Aarons was immediately sent to Egypt. Once

in Cairo he checked into the "Yank" office, run by Hodding

Carter. He was attached to the British because there were no American

troops there.

"We go up to the front with the British. There was an incredible

bombardment. We are living in foxholes we can hear the British planes

going over and one American unit, the 57th fighter group."

"War in the desert is not like war anywhere else in the world.

You can see nothing. If you see a tank he can kill you and you can kill

him so you have to get away. They [the Germans] are using ambulances

to bring weapons, and so are we. I'm telling you the way it was, because

in war there are no rules. I'm getting bombed. I'm a kid in the slit

trenches,and the Germans are coming over at night. It's not like today

where you have radar and all that we had nothing."

Slim Aarons' experience was not without humor. In Italy, he asks soldiers

at the ration dump for flour so that the bakers in town, who had none,

could make bread for the nurses. The bakers give him a casket of wine

in return. Aarons brings it back to the press corps. Ernie Pyle reacts

quickly, "Ernie liked his booze, and he said,'Where did you get

the wine? And he said, 'By any chance did they have any liquor?’"

Aarons explains that the Army furnishes whiskey to the nurses for the

wounded. Pyle is anxious to meet the man at the ration dump. On arrival,

Pyle says that he wants to do a story on the people who handle the rations.

Then he asks about the nurses' whiskey. The men say, "Oh no,Mr.

Pyle, you wouldn't like it, it's just raw whiskey." Pyle goes on,

"Well, you know, I am a good journalist. Would it be possible to

taste this raw whiskey?" He is brought a bottle that reads "U.S.

Army MedicalCorps." Pyle agrees that it is a little raw but not

bad, he added, "you know how it is, when you write a story you

really have to learn and maybe I can get some for my friends for a full

opinion of it." He gets his bottle. It was the first exchange in

a long relationship with the ration dump.

The tone is much different when Aarons goes close to the front at Monte

Cassino. He is led into the area through mortar fire by New Zealand

guides. "I was so scared I shit in my pants…I was scared to

death. You don't know what it is to go into a place where everybody

is trying to kill you." That evening he ends up in a damaged building

with soldiers. "I go to my camera-and how can you take a picture

when you can't go outside? You can't even think about going outside,

you can only shoot through that hole and you don't see much from the

hole, because its night. The Germans are screaming, there are star shells,

and you think,'Jesus what am I doing in here? “You can't do a goddamn

thing, you can't take pictures. War is not simple it's not like in the

movies."

On the way into Rome, the troops were delayed. "The women loved

them so much they held up the troops! These guys who had been in Anzio...really

rough guys. They (the women) were grabbing them and throwing them in

beds and raping them! See this is real war!”

Aarons took photos in a nunnery near Naples for an Italian magazine.

He was struck how lovingly the Italians accepted children fathered by

the troops. He found one child that had neither arms nor legs. The boy

was learning to read Braille with his tongue. No newspaper would run

the photograph. It was too strong. "Here is a kid with no arms,

no legs, he was blind and he was trying to learn and read with his tongue!

The will to learn and the will to want to get ahead...that's what I

learned. The rest is bullshit!”Following World War II, Slim became

one of the most famous fashion and lifestyle photographers of the last

part of the 20th Century. His photographs of the beautiful life of the

rich and famous were featured in countless issues of “Harper's

Bazaar,””LIFE”, and “Town and Country.” His

book "A Beautiful Place" now sells for more than $3,000, and

is highly sought by collectors.

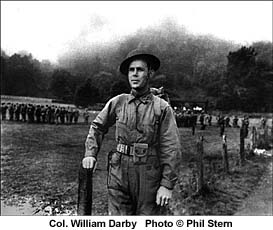

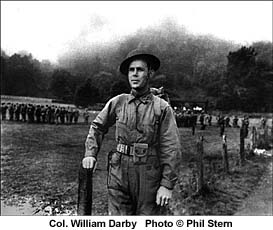

PHIL STERN

Phil

Stern became one of the most preeminent photographers to cover Hollywood

and the film industry through the 50s, 60s, and 70s. His photographs

of James Dean were made into posters, and he produced books on film

and jazz. Today, he lives in a small house behind Paramount studios

in Los Angeles. If you are a book or television producer looking for

the photographs of Hollywood at it's zenith, Phil's house is the mother

lode. Phil

Stern became one of the most preeminent photographers to cover Hollywood

and the film industry through the 50s, 60s, and 70s. His photographs

of James Dean were made into posters, and he produced books on film

and jazz. Today, he lives in a small house behind Paramount studios

in Los Angeles. If you are a book or television producer looking for

the photographs of Hollywood at it's zenith, Phil's house is the mother

lode.

What most of the people visiting his house and browsing through the

drawers of his vast print collection don't know, is that Phil in the

1940s was a Ranger with a camera. Like Slim Aarons, he was recruited

by a reserve officer who worked at Paramount after Pearl Harbor. He

said "look, Phil, you are y young and healthy...you are going to

get drafted. So why don't you volunteer and we will make sure that you

get to do what you love doing, photography, instead of driving some

truck." Which is how a 20-year old found himself on a train, bound

for Astoria, Long Island, to enter the Army Signal Corps.

While Slim Aarons was following the British 8th Army as it fought its

way across Africa to engage Rommel, Phil was getting ready to come in

the other way with American forces. . In London, he had been assigned

to a photo lab doing "grip and grins." Then one day he saw

an advertisement in Stars and Stripes, offering a life of adventure

to anyone who could make the qualifications for a new elite outfit being

assembled in Scotland. It was a group to be know as "Darby's Rangers",

named after its macho leader. When Darby took one look at Phil, he wondered

what on earth this kid was doing volunteering to be a Ranger. Phil responded,

“Colonel, you are going to be doing an important job and you deserve

to be documented." He was in.

He was in Africa. He was at the Kazarine pass when Rommel almost wiped

out the allied force. He was in Sicily, going in with the first waves

of Rangers. He carried a 4x5 speed graphic, but hated it. At one point,

he threw it over a cliff in Italy, only to have the Signal Corps send

him another one. Then in Italy, his number almost came up, advancing

across a field with tanks, he was wounded, and the war was over for

him.

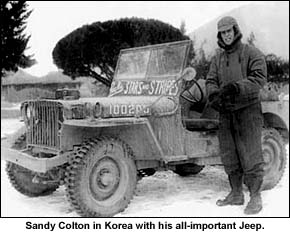

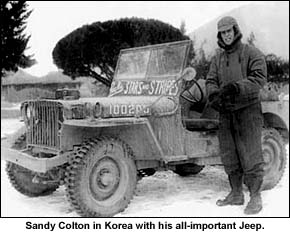

SANDY COLTON

During

1948 and 1949 Sandy Colton was in the Air Force serving on Guam and

in Tokyo. Primarily a writer, many of his articles appeared in the"Pacific

Stars and Stripes." He wanted to join the staff but the newspaper

was still an Army publication. During

1948 and 1949 Sandy Colton was in the Air Force serving on Guam and

in Tokyo. Primarily a writer, many of his articles appeared in the"Pacific

Stars and Stripes." He wanted to join the staff but the newspaper

was still an Army publication.

When the Korean War started in 1950, he was in Korea where he wanted

to be. "My stories were bylined in the 'Stripes' almost daily and

many of my stories were picked up by the wires and sent on word for

word, sometimes with someone else's by-line.

"In the meantime

the ‘Pacific Stars and Stripes’ had become an all service

paper with men and women from the Navy, Marines, and Air Force, as well

as the Army. " Colton was stationed about five miles from Pusan.

Through contacts, Colton was released from the Air Force command and

assigned to the Tokyo "Stars and Stripes". "I returned

to Korea with orders to do a feature on every outfit over there.

"This was the real beginning of my professional life. I never wore

my sergeant's stripes, just the 'Stars and Stripes' patch. As I traveled

from unit to unit I was treated with the same dignity as the civilian

corespondents covering the war." He was introduced to Kent Cooper,

then the AP bureau chief. (Cooper was the person responsible for seeing

through the introduction of Wirephoto.) Colton would later have a distinguished

career at The Associated Press.

Colton spent months traveling in Korea "on my thumb." Later

he had the exceptional luck of getting a jeep through friends, a jeep

that "had no hood or windshield, only one seat for the driver,

the engine leaked water that would hit the fan and blow back onto the

driver." Nevertheless, it was a treasured possession. During his

interview he elaborated.

"It was the jeep. If there was any one thing that made life different

for the soldier photographer that covered the battlefields of Europe,

the Pacific, and Korea for 'Stars and Stripes' and 'Yank Magazine' it

was the jeep. Unlike the dogfaces and grunts that trekked across the

warscape, braving enemy fire, heat, cold, rain and snow, the photographers

could move quickly, and independently. No one provided them with the

vehicles. They had to beg or steal them, and once the had one, they

weren't about to lose it."

In Korea, Sandy Colton also made gritty photographs of real life during

the war. "Mostly I shot my own pictures to illustrate my stories.

I carried a 35mm Nikon and a Yashikamat 120 camera. I remember meeting

a LIFE photographer, Bob Landry, who said to me, 'You're a little over

equipped aren't you, son?' He was right. After that I carried only the

Nikon." Unlike other journalists, he did not rely on the Signal

Corps or other photographers; he knew how to tell a story with words

and in pictures.

RED GRANDY

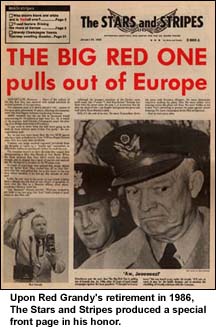

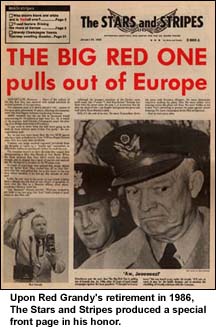

Red

Grandy worked at "The Stars and Stripes" in Germany from 1951

until 1986. When he first arrived at Darmstadt, West Germany, he used

a 4 x 5 camera that he replaced with a Rolleiflex. Later he would use

a 35mm. Red

Grandy worked at "The Stars and Stripes" in Germany from 1951

until 1986. When he first arrived at Darmstadt, West Germany, he used

a 4 x 5 camera that he replaced with a Rolleiflex. Later he would use

a 35mm.

Some assignments were mundane but necessary for troop morale. The newspaper

also had access to AP, UPI and used those photographs alongside those

made by the staff.

Grandy tells the story of one of his most famous pictures. He was there

to watch Gen. Eisenhower review the troops…. We heard the Truman

had fired (Gen.) McArthur (in Korea)…Ike hadn't found out about

it. I told the other photographers if WE told him about it, with his

rubber face, we would get a picture." A reporter does get the information

to Ike and he looked away in disbelief. "I flashed my Speed Graphic

and [later] he sent me a copy signed, 'To Red Grandy who surprised and

old soldier.'" The magazine didn't use it. Finally it was published

as a one-column picture. After that exposure LIFE magazine and other

periodicals picked it up.

He recalls the during WWII, "S&S people would come into a town,

and just go to the printing plant, and just took them over, started

to produce to paper the next days…. The Germans had wrecked a lot

of their linotype machines, but they (the S&S staff) were very aggressive

people…they just managed to do it.

"We used the trains, German trains, planes, burros, donkeys…jeeps…we

had the circulation people—very enterprising --(find) any means

they could…. The routes (were) big. No paper in the US had routes

from Turkey to Iceland."

JOHN OLSON

"I

remember coming home from school one day in the mid 1960s and opening

Life magazine, and seeing Larry Burrow's 'Yankee Papa 13' story from

Vietnam--from that day on, that is where I wanted to be.", "I

remember coming home from school one day in the mid 1960s and opening

Life magazine, and seeing Larry Burrow's 'Yankee Papa 13' story from

Vietnam--from that day on, that is where I wanted to be.",

After graduation

Olson joined UPI and 30 days later was drafted into the Army. Seemingly

headed in the right direction, it took some maneuvering to join "The

Stars and Stripes." He had to promise the Saigon bureau reporters

that he would not ask them to go into combat with him because of the

danger. He was probably one of a very few people in the American military

that set foot in the three biggest battlegrounds of the war, Khe Sanh,

The Battle of Saigon during the 1968 Tet Offensive, and the battle of

Hue.

During the Tet offensive of 1968 (the Vietnamese lunar new year) the

North Vietnamese attacked major cities at the same time. In addition

to Saigon they went after the old imperial section of Hue. "Hue…was

not only a significant turning point in my life, it was also one of

the most significant battles of the war." After assuming travel

was by helicopter, as usual, bad weather and heavy fighting meant that

he went in on a landing craft with a bunch of Marines.

"I was in Hue for five days. I had been in Vietnam for one year

at this time…I had seen a lot of battles and I thought I was pretty

experienced, But I had never seen anything like Hue…Tremendous

bravery, a lot of dead." At one point Marines were moving across

a courtyard, and they were rocketed, causing many casualties. They had

no radio contact. "We were pinned down and in pretty bad shape.

We had an element that eventually came to relieve us and it had a priest…The

priest gave last rites to the dead, and he was a very generous priest--he

offered to give the last rites to any of us that wanted them (whether)

dead, wounded or not scratched at that point. "The photograph of

the tank was a moment that at time of capture, didn't stand out to me

at all…just another image…in context it was such a horrific

battle with such horrific images. Hue was different; there were tremendous

casualties, and no way to treat them...no way to get them medivaced.

…In this image there was a Marine that was badly wounded…so

badly wounded he couldn't be treated and he was zipped up in a body

bag while he was still alive…. That's what Hue was like.”

It was that hellish

battle that resulted in the pictures of US Marines underfire that ran

in Life Magazine, and won him the Robert Capa Award. At 21, after leaving

the Army, he was hired as Life's youngest staff photographer.

"The Stars and Stripes" gathered in its ranks, loyal, passionate

people. They were committed to getting the story and thus bring the

Army into a tighter community. The paper may have been a product of

the "military" but it was a large tabloid -sized newspaper

the covered the world and celebrated the soldiers daily lives.

Today the European and Pacific versions have become one, published in

Washington, D.C. Original copies of "The Stars and Stripes"

are located in bound volumes in both Darmstadt, Germany and at the central

library in Washington DC The photo archive in Germany holds close to

one-half million photos dating back to the beginning of WWII. There

are no archives online, but the New York Public Library has microfilm

for public use. The museum commemorating the newspaper is in Bloomfied,

Illinois (Charlene Neuwiller, Library, Washington, DC)

Click

to view the pictures

by these photographers:

Visit

The Stars and Strpes online

and read

more about its history.

|

The

name itself has a journalistic history: in short, during the Civil War

there were at least four different editions of "The Stars and Stripes."

The basic tenets for the military newspaper were set in Paris during

World War I, according to Ken Zumwalt in his book, "The Stars and

Stripes: World War II and the Early Years", (1989). The first military

newspaper was published at Bloomfield, Missouri, on November 9, 1861

for the soldiers of the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteer Regiments.

In 1917, the American Expeditionary Force landed in France under the

command of General John Pershing. Pershing authorized a newspaper to

be "written by soldiers for soldiers" He went on to declare

that it should be free of censorship by field commanders [from: www.stripes.com].

"The Stars and Stripes" of this era published 7I weekly issues,

from February 8, 1918 - June 13, 1919.

The

name itself has a journalistic history: in short, during the Civil War

there were at least four different editions of "The Stars and Stripes."

The basic tenets for the military newspaper were set in Paris during

World War I, according to Ken Zumwalt in his book, "The Stars and

Stripes: World War II and the Early Years", (1989). The first military

newspaper was published at Bloomfield, Missouri, on November 9, 1861

for the soldiers of the 18th and 29th Illinois Volunteer Regiments.

In 1917, the American Expeditionary Force landed in France under the

command of General John Pershing. Pershing authorized a newspaper to

be "written by soldiers for soldiers" He went on to declare

that it should be free of censorship by field commanders [from: www.stripes.com].

"The Stars and Stripes" of this era published 7I weekly issues,

from February 8, 1918 - June 13, 1919. George

"Slim" Aarons began as the official photographer at West Point

in the early 1940s. There he met the movie director Frank Capra, who

during those years was working on movies for the army and charged with

setting up the magazine "Yank." This new weekly magazine was

to come out with the newspaper, S&S.

George

"Slim" Aarons began as the official photographer at West Point

in the early 1940s. There he met the movie director Frank Capra, who

during those years was working on movies for the army and charged with

setting up the magazine "Yank." This new weekly magazine was

to come out with the newspaper, S&S. Phil

Stern became one of the most preeminent photographers to cover Hollywood

and the film industry through the 50s, 60s, and 70s. His photographs

of James Dean were made into posters, and he produced books on film

and jazz. Today, he lives in a small house behind Paramount studios

in Los Angeles. If you are a book or television producer looking for

the photographs of Hollywood at it's zenith, Phil's house is the mother

lode.

Phil

Stern became one of the most preeminent photographers to cover Hollywood

and the film industry through the 50s, 60s, and 70s. His photographs

of James Dean were made into posters, and he produced books on film

and jazz. Today, he lives in a small house behind Paramount studios

in Los Angeles. If you are a book or television producer looking for

the photographs of Hollywood at it's zenith, Phil's house is the mother

lode. During

1948 and 1949 Sandy Colton was in the Air Force serving on Guam and

in Tokyo. Primarily a writer, many of his articles appeared in the"Pacific

Stars and Stripes." He wanted to join the staff but the newspaper

was still an Army publication.

During

1948 and 1949 Sandy Colton was in the Air Force serving on Guam and

in Tokyo. Primarily a writer, many of his articles appeared in the"Pacific

Stars and Stripes." He wanted to join the staff but the newspaper

was still an Army publication.  Red

Grandy worked at "The Stars and Stripes" in Germany from 1951

until 1986. When he first arrived at Darmstadt, West Germany, he used

a 4 x 5 camera that he replaced with a Rolleiflex. Later he would use

a 35mm.

Red

Grandy worked at "The Stars and Stripes" in Germany from 1951

until 1986. When he first arrived at Darmstadt, West Germany, he used

a 4 x 5 camera that he replaced with a Rolleiflex. Later he would use

a 35mm.  "I

remember coming home from school one day in the mid 1960s and opening

Life magazine, and seeing Larry Burrow's 'Yankee Papa 13' story from

Vietnam--from that day on, that is where I wanted to be.",

"I

remember coming home from school one day in the mid 1960s and opening

Life magazine, and seeing Larry Burrow's 'Yankee Papa 13' story from

Vietnam--from that day on, that is where I wanted to be.",