|

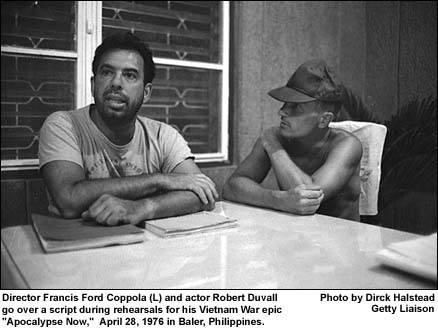

"We were in the jungle. There were too many of us. We had access

to too much money, and little by little, we went insane." Francis

Ford Coppola in an interview about the making of Apocalypse Now.

It

was almost a year to the day since I had flown over the Philippines

aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft on my way out of Vietnam, following the

collapse of Saigon in April of 1975. It

was almost a year to the day since I had flown over the Philippines

aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft on my way out of Vietnam, following the

collapse of Saigon in April of 1975.

The ancient Commercial Air Transport DC3 I was riding on bumped and

bucked its way down through torrential tropical rain onto a dirt strip

carved out of the jungles of Luzon. The runway lights were kerosene

lanterns. I was arriving at the most unlikely movie location imaginable.

I had been invited to spend a week documenting the making of Apocalypse

Now.

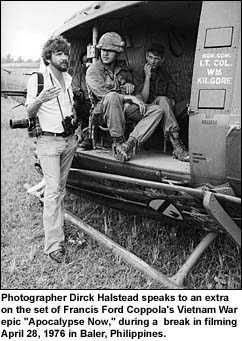

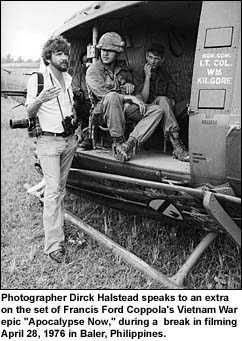

Photographing on movie sets was nothing new to me. As well as being

a Time contract photographer covering news, features, and The White

House, I would regularly work as a "special" photographer

for the movie industry. Going in, though, I had no idea how very different

a project this would be from anything I had known. I was entering a

strange world where art and reality were confused, and the professionalism

of a big budget movie unit, which I was used to, would be threatened

by delusion and madness.

In the late 1960s, America was becoming ever more bogged down in the

quagmire that was Vietnam. Writer John Millius, at the request of director

Francis Ford Coppola, wrote a screenplay based on Joseph Conrad's 19th-century

book Heart of Darkness. The story of a ship captain who journeys

up a river in the Congo searching for an ivory trader named Kurtz. In

the process he finds himself not only leaving civilization, but also

entering the dark realm of evil that resides in people's souls.

Coppola wanted to reset the story in Vietnam and draw the characters

from that war. At one point, he even considered shooting the film in

Vietnam, using 16mm cameras. He assembled a talented cast and crew who

were more than willing to risk their lives to make the film. However,

it was more than Warner Brothers could tolerate, and the project was

put on the back burner. In the years that followed, Coppola went on

to produce The Godfather and The Godfather II, and in

the process became one of the richest and most powerful filmmakers in

the world.

In early 1976, Coppola decided to try again. United Artists put up $18

million as a budget. Production was scheduled to start in February of

1976 on the island of Luzon in the Philippines.

In

order to convince UA to put up the money, Coppola had signed a contract

with Marlon Brando to play the role of Colonel Kurtz, a former Green

Beret commander who has gone mad. Brando was to get a million dollars

a week for three weeks of work. It was a classic "Play or Pay"

deal, which meant that Brando would be paid regardless of whether he

actually worked or not. This deal pushed pre-production ahead much faster

than normal. Also, in order to get the cooperation of the Philippine

military which controlled the helicopters, tanks, and planes, a financial

agreement had to be put in place, and a firm start date had to be set.

The shooting schedule for principal photography was to run about sixteen

weeks. But it was 2 years and 238 shooting days later before Apocalypse

Now was finally in the can. In

order to convince UA to put up the money, Coppola had signed a contract

with Marlon Brando to play the role of Colonel Kurtz, a former Green

Beret commander who has gone mad. Brando was to get a million dollars

a week for three weeks of work. It was a classic "Play or Pay"

deal, which meant that Brando would be paid regardless of whether he

actually worked or not. This deal pushed pre-production ahead much faster

than normal. Also, in order to get the cooperation of the Philippine

military which controlled the helicopters, tanks, and planes, a financial

agreement had to be put in place, and a firm start date had to be set.

The shooting schedule for principal photography was to run about sixteen

weeks. But it was 2 years and 238 shooting days later before Apocalypse

Now was finally in the can.

I awoke before dawn to the sound of roosters and pigs. My bedroom was

on the second floor of the house belonging to the Mayor of Luzon. Coppola

had taken it over as his production offices, and to house occasional

guests. There was no air conditioning. Even at that early hour the temperature

was in the nineties, and the humidity was 100%. There was not even a

hint of breeze.

Groggy, I stumbled out of the house as dawn started to streak the sky.

All of a sudden there was a roar overhead I hadn't heard for a year.

It was the unmistakable drone of UH-1B military helicopters coming in

to land. I blinked as I looked up and saw the familiar olive-drab colors

and insignia of the US Army 1st Cavalry Division on the sides. Helmeted

door-gunners were clearing their M60 machine guns as the choppers sat

down in the town square. A jeep came roaring around a corner, another

gunner standing behind its machine gun. Orders were being barked as

troops came spilling out of their barracks and formed into lines to

prepare for inspection. Vietnamese civilians were boiling the broth

for their morning pho in front of their hootches. There wasn't

a movie camera in sight. Somehow, overnight, I had been transported

through time and space back to Vietnam in the 1960s.

What Coppola had done was to send his scouts to every bar across the

Philippines, and signed up any expatriate who looked like he could be

a US soldier. There were Germans, Norwegians, Brits, and Americans who

signed on for months of living in cold-water barracks so they could

play soldier.

To whip them into shape, his military advisors, including Lt. Col. Peter

Kama (US Army, Ret.), were brought in. They achieved a remarkable transformation

in these would-be grunts during a two-week drill. At breakfast in the

mess hall, I sat across from a young man who had worked as an editor

for City Magazine in San Francisco. During the Vietnam War he

had fled to Canada to avoid the draft. Yet here he was, dressed in tropical

fatigues, dog tags dangling from his neck. There was a strange gleam

in his eyes as he told me that his "platoon" was the best

in the unit. They had perfected jumping from hovering helicopters, digging

in, and setting up a defensive perimeter in minutes. They called their

group "The Donald Ducks." He proudly exclaimed, "If we

had been in Vietnam we would have won that war!"

Coppola

had also done more than his part in relieving the Philippine authorities

by caring for hundreds of Vietnamese refugees that had come to their

shores. He moved them to Luzon. They set up their own villages right

on the set. Meanwhile, up the river, 600 Filipino workers were busy

constructing Kurtz's temple out of 300-pound dried adobe blocks, under

the direction of production designer Dean Tavoliarius. To play the headhunters

Kurtz had recruited in his jungle stronghold, Coppola transported a

tribe of Ifugao Indians from the south. It was rumored that until recently

the tribe had still practiced headhunting for real. Coppola

had also done more than his part in relieving the Philippine authorities

by caring for hundreds of Vietnamese refugees that had come to their

shores. He moved them to Luzon. They set up their own villages right

on the set. Meanwhile, up the river, 600 Filipino workers were busy

constructing Kurtz's temple out of 300-pound dried adobe blocks, under

the direction of production designer Dean Tavoliarius. To play the headhunters

Kurtz had recruited in his jungle stronghold, Coppola transported a

tribe of Ifugao Indians from the south. It was rumored that until recently

the tribe had still practiced headhunting for real.

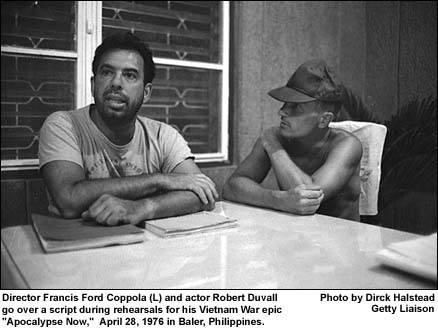

My visit coincided with the start of the biggest "set piece"

of action in the film. This was the famed Air Cavalry attack on the

Vietcong village. Production on the film had already been underway for

little more than a month, and already Francis was bedeviled by circumstances

that were spinning out of his control. Harvey Keitel was his first choice

for the actor playing the lead role of Capt. Willard who makes the long

journey up the river to find Kurtz and to "terminate with extreme

prejudice." Keitel was fired after a week of shooting, which meant

the first week of film was now useless. Coppola flew to Los Angeles

and signed Martin Sheen to replace Keitel.

Meanwhile, the Philippine Air Force was becoming increasingly difficult

as far as keeping their promises. After Coppola had paid enormous sums

to rent, and in many cases, re-equip their helicopters, they would suddenly

disappear in the middle of filming to fly off to engage real-life rebel

forces in the hills.

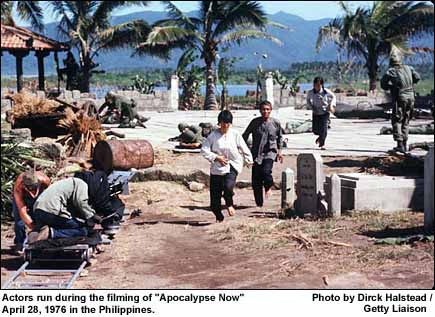

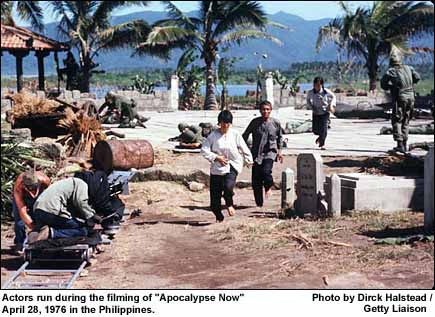

My first day on the set, the attack on the village was being shot. Coppola

acknowledged this was the most complicated sequence of filming in his

career. Explosive charges had been wired throughout the village. As

Coppola called "Action!" Vietnamese extras ran toward machine

gun emplacements and opened fire on the oncoming helicopters. Buildings

exploded, bullets ripped up the ground. As the helicopters, spewing

rockets, machine guns blazing, roared overhead, the Assistant Director

yelled, "Cut!" Director of Photography Vittorio Storaro complained

that the helicopters were too high. They were not in the shot.

For the next four hours, the set was prepared again. New charges were

put in place. With the light beginning to fade, Coppola yelled "Action!"

and once more the guns began to fire and Vietnamese ran across the long

bridge that had been rigged to explode. Then, suddenly, the lead Huey

veered off to the south, followed by the rest of the squadron. As the

choppers disappeared into the distance, the Philippine Air Force Liaison

Officer told Coppola that they had been called off the filming to attack

a rebel force.

"This

film is a 20-million-dollar disaster. Why won't anybody believe me?

I'm thinking of shooting myself!" (Francis Ford Coppola, April,

1976)

Coppola was discovering that he was unwittingly replicating the American

experience in Vietnam, with all this equipment, all these people, he

was losing every day, and he was the commanding general. He had to beg

United Artists to put another $3 million in the budget, which the studio

agreed to do, but only on the condition that if the film made less than

$40 million, Coppola would be held personally responsible for repaying

the extra money.

Marlon Brando insisted he play his role according to the original schedule,

or he would simply cash the million dollars a week he had been promised.

But Coppola was a long way from that point. The original script had

been made irrelevant. Daily call sheets for cast and crew would simply

say "scene unknown." Now he was directing by the seat-of-his-pants.

He was starting to commit the worst crime a director can be accused

of, he was shooting impulsively, letting things "happen."

In the process he was throwing away narrative structure. He had moved

too far up the river in his own mind to turn back.

"My greatest fear is to make a really shitty, embarrassingly

pompous film on an important subject, and I'm doing it. I confront it.

I acknowledge, I will tell you right straight from the most sincere

depths of my heart, the film will not be any good." (Francis

Ford Coppola in an interview with his wife Eleanor)

Drugs, alcohol, and delirium became the norm. Actors and crew were dropping

acid or taking speed. At times, this resulted in astonishing performances.

While preparing to shoot what would become the opening scene for the

movie, with Martin Sheen playing Willard, Coppola had been told by an

advisor that a real green beret would be a vain, narcissistic man who

would likely spend hours looking at himself in a mirror. After making

this suggestion to Sheen, who was already feeling the effects of the

long shoot in the jungle, he decided to go for his own style of "method

acting." After consuming prodigious amounts of liquor, he started

the shot, doing karate moves, naked, in front of a mirror. As the alcohol

took over, he lunged forward and shattered the mirror with his hand.

It split open his thumb. Coppola immediately called "Cut,"

and shouted for a doctor. Sheen, however, insisted the filming continue.

Over the next half hour, the bleeding actor slouched against a bed cursing

at the camera and the director. Crew members feared Sheen might become

violent. The resulting performance is one of the most gripping in acting

history.

Then came the storm. In May, a giant typhoon smashed the Philippines.

It wrecked many of the sets. The film was forced to shut down for two

months. By now, Coppola had hocked many of his assets, including his

home in Northern California. By July, filming restarted, but where the

story was going was anybody's guess. Coppola did a major scene, which

took place on a French plantation that the crew of the River Patrol

Boat encounters on their trip up the river. The plantation and its owners

represented the colonial history of Vietnam. Meticulous attention was

paid to every detail. The white wine would be served at 50 degrees,

and the red at room temperature after breathing for an hour and a half.

It was one of the most evocative scenes of the movie, but Coppola hated

it. Because of his budget pressure, he couldn't afford the French cast

he wanted, and after a week of shooting he decided to kill the entire

scene.

In the motion picture industry, wags began to talk about "Apocalypse

Later." There were rumors that Coppola had suffered a breakdown.

Bizarre stories circulated. Had real body parts been taken from cemeteries

to be used in the Kurtz-temple scenes? And then, in July of 1977, Martin

Sheen had a major heart attack on the set. He was out of action for

six weeks. During that time the director and crew would spend days on

the boat, wandering the river, trying to conceive of shots. Each day

they would go further up the river. Coppola would lay down clouds of

smoke, which made each trip seem further and further from reality.

Then there was the tiger scene. Francis came up with the idea that the

crew of the PBR would get off the boat to find some mangos. Frederick

Forrest and Martin Sheen suddenly came face to face with a charging

tiger. The trainer, Marty Cox, who had been severely mauled by one of

his charges, told the crew that he had not given the tiger anything

to eat for a week, and he was "plenty hungry." A small pig

was dragged toward the camera to make the tiger charge, but once the

animal burst through the jungle, the cast and crew panicked. Frederick

Forrest later said "I was never so scared in my life. It was so

fast, man...guys were running everywhere...climbing trees. To me, that

was the essence of the whole film in Vietnam. The look in that tiger's

eyes...the madness...there was no reality any more...if he wanted you,

you were his." As they said in the movie, "Never get off the

goddamned boat!"

Then, into all this chaos, came Brando. It was the event Coppola feared

the most. Finally, he would be forced to confront the ultimate narrative

of his story. How was all of this going to end? When he had been hired

two years earlier, Brando was already overweight, living a life of indulgence

on his Pacific island paradise. He had promised to get into shape for

the film, but when he finally arrived on the set he was heavier than

ever, and extremely sensitive about his girth.

One way out of the Brando predicament for Coppola was to use the fact

of Brando's weight as a physical example of how living outside civilization,

in the jungle, had caused this Green Beret to let himself go. But Brando

wouldn't hear of it. Somehow, they would have to shoot him in semi-darkness.

Next problem, what was he going to say? There was no script. For long

days, with the Brando million-dollar-a-week meter running, the star

and director would huddle on the set trying to come up with anything

that they could shoot. Finally, Coppola decided to let Brando improvise.

He figured that if he just kept shooting, sooner or later something

would make sense.

"This movie was not made in the tradition of Max Ophuls or David

Lean. It was made in the tradition of Irwin Allen. I made the most vulgar,

entertaining, actionful, sense-a-ramic, give them a thrill every five

minutes, sex, violence, humor, because I want people to come see it.

But the questions I kept running into and facing every 5 seconds was

the stupid script! Going up the river to kill a guy, but that was the

story! The questions that story kept putting to me, I couldn't answer,

yet I knew I had constructed the film in such a way that not to answer

would be to fail. (Francis Ford Coppola in an interview with his

wife Eleanor.)

Finally, Francis was forced to call it quits in Luzon. But the film

still did not make sense. More scenes were scripted and shot in Northern

California. Michael Herr, an author who had written one of the best

books about the Vietnam War, was hired to construct a narrative that

would link the scenes. It was largely Herr's words that Martin Sheen

speaks as the PBR goes up that river.

On August 19, 1979 the movie opened. I was in the audience at the Ziegfeld

Theater in New York City. Until that point, no one had ever made a movie

about Vietnam that I thought was right. Details might be correct, the

history solid, but they had all missed something crucial. Perhaps it

was the rock-n-roll we all associated with that time and place. But

sitting in the dark, looking up at that screen, I knew Coppola had got

it right. Maybe the reason was that the war had made no sense, and in

his own search to sort it all out, he came to the only real truth of

that struggle, that everyone was mad.

The movie won three Golden Globe Awards, two Academy Awards, and the

Cannes Film Festival's Palme d'Or. It made $150 million at the box office.

Oh, but the story wasn't over. Coppola knew it.

Over the next 20 years, he would think about all the unused material

from the original 4-hour assembly. What about the plantation scene?

What ever happened to the Playboy Bunnies that entertained the troops?

There were many unanswered questions.

This month some of those questions will be answered. A new version,

nearly an hour longer than the original, opens in theaters around the

country. Will the changes make this classic film even better? I don't

know. But maybe now Francis Ford Coppola can finally "get off the

goddamned boat."

Visit

the Apocalypse Now website

Dirck

Halstead is the Editor and Publisher of The Digital Journalist monthly

webmagazine. In 1976, he was awarded the Robert Capa Gold Medal for

his coverage of the Fall of Saigon for Time Magazine.

|

It

was almost a year to the day since I had flown over the Philippines

aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft on my way out of Vietnam, following the

collapse of Saigon in April of 1975.

It

was almost a year to the day since I had flown over the Philippines

aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft on my way out of Vietnam, following the

collapse of Saigon in April of 1975. In

order to convince UA to put up the money, Coppola had signed a contract

with Marlon Brando to play the role of Colonel Kurtz, a former Green

Beret commander who has gone mad. Brando was to get a million dollars

a week for three weeks of work. It was a classic "Play or Pay"

deal, which meant that Brando would be paid regardless of whether he

actually worked or not. This deal pushed pre-production ahead much faster

than normal. Also, in order to get the cooperation of the Philippine

military which controlled the helicopters, tanks, and planes, a financial

agreement had to be put in place, and a firm start date had to be set.

The shooting schedule for principal photography was to run about sixteen

weeks. But it was 2 years and 238 shooting days later before Apocalypse

Now was finally in the can.

In

order to convince UA to put up the money, Coppola had signed a contract

with Marlon Brando to play the role of Colonel Kurtz, a former Green

Beret commander who has gone mad. Brando was to get a million dollars

a week for three weeks of work. It was a classic "Play or Pay"

deal, which meant that Brando would be paid regardless of whether he

actually worked or not. This deal pushed pre-production ahead much faster

than normal. Also, in order to get the cooperation of the Philippine

military which controlled the helicopters, tanks, and planes, a financial

agreement had to be put in place, and a firm start date had to be set.

The shooting schedule for principal photography was to run about sixteen

weeks. But it was 2 years and 238 shooting days later before Apocalypse

Now was finally in the can. Coppola

had also done more than his part in relieving the Philippine authorities

by caring for hundreds of Vietnamese refugees that had come to their

shores. He moved them to Luzon. They set up their own villages right

on the set. Meanwhile, up the river, 600 Filipino workers were busy

constructing Kurtz's temple out of 300-pound dried adobe blocks, under

the direction of production designer Dean Tavoliarius. To play the headhunters

Kurtz had recruited in his jungle stronghold, Coppola transported a

tribe of Ifugao Indians from the south. It was rumored that until recently

the tribe had still practiced headhunting for real.

Coppola

had also done more than his part in relieving the Philippine authorities

by caring for hundreds of Vietnamese refugees that had come to their

shores. He moved them to Luzon. They set up their own villages right

on the set. Meanwhile, up the river, 600 Filipino workers were busy

constructing Kurtz's temple out of 300-pound dried adobe blocks, under

the direction of production designer Dean Tavoliarius. To play the headhunters

Kurtz had recruited in his jungle stronghold, Coppola transported a

tribe of Ifugao Indians from the south. It was rumored that until recently

the tribe had still practiced headhunting for real.