by Susan Markisz

News Photographer

David Handschuh has been running after New York stories for the past

twenty years. But on the morning of September 11, the story he was

pursuing sent him running for his life. For Handschuh and other photographers,

the day began as an ordinary workday. Some were deployed throughout

the city covering the mayoral primary while others were visually taking

the City’s early morning quotidian pulse.

At

8:46 a.m. the ordinary became the extraordinary as voices over police

and fire scanners reported ominous sounding information of what was

first assumed to be an errant private plane hitting the north tower

of the World Trade Center. Moments later came terrifying details of

a second plane, a commercial airliner slamming into the south tower,

sending photographers into combat mode, scrambling to find the quickest

route downtown. Within minutes, photographers who had made their way

to the scene, found themselves in mortal danger along with firefighters,

police and rescue workers. Within the hour, photographers were wiping

away tears, while at the same time producing stunningly surreal images,

destined to become embedded in our national collective psyche. By

the end of the day, the New York primary had become a footnote---history

deferred---to an ignominious terrorist attack on New York City’s

World Trade Center, leaving more than 5,000 dead or missing, and injuring

thousands more.

At

8:46 a.m. the ordinary became the extraordinary as voices over police

and fire scanners reported ominous sounding information of what was

first assumed to be an errant private plane hitting the north tower

of the World Trade Center. Moments later came terrifying details of

a second plane, a commercial airliner slamming into the south tower,

sending photographers into combat mode, scrambling to find the quickest

route downtown. Within minutes, photographers who had made their way

to the scene, found themselves in mortal danger along with firefighters,

police and rescue workers. Within the hour, photographers were wiping

away tears, while at the same time producing stunningly surreal images,

destined to become embedded in our national collective psyche. By

the end of the day, the New York primary had become a footnote---history

deferred---to an ignominious terrorist attack on New York City’s

World Trade Center, leaving more than 5,000 dead or missing, and injuring

thousands more.

In a city where local photographers are often grounded on national

news stories, New York City became the literal and figurative epicenter.

As iconic twin towers symbolically---and now precariously---stood

guard at the southern tip of Manhattan, photographers going about

their daily assignments were reassigned to an unfolding disaster of

epic proportions. Local news was eclipsed by a monumental human toll,

buried underneath twisted steel and wreckage. Wire services transmitted

images almost instantaneously to a world in shock and newspapers and

magazines produced comprehensive visual editions of the attacks on

the World Trade Center. The New York Times produced a special section

called “A Nation Challenged” devoted to continuing coverage

of the Word Trade Center attacks and the aftermath. Time, Newsweek

and U.S. News and World Report each produced special editions that

sold out almost immediately to a citizenry that needed visual acknowledgment

that the unimaginable actually did happen.

With the country in mourning, photographers on the front lines quietly

produced some of the most astonishing images the world has ever seen;

astonishing in part because of the nature of the tragedy; in part

because of the speed of dissemination, in part because photographers

were eyewitnesses to events as they unfolded, not only as after-the-fact

documentarians. Two photographers lost their lives, others faced life

threatening injuries and many, perhaps not surprisingly, have experienced

emotional trauma.

Handschuh,

a staff photographer for The Daily News, was scheduled to teach a

graduate class in photojournalism at NYU in the morning, and cover

late election results at night for the News. While cruising around

Manhattan’s West Side on his way to class, he heard voices from

Manhattan Fire on the scanner screaming to send every piece of apparatus

available to the World Trade Center. As W. 43rd Street’s Rescue

One rushed southbound, Handschuh swerved across the traffic island

on the West Side Highway, and followed them on their rear bumper,

observing their preparations as they threw on their packs, readied

their oxygen tanks, and placed tools in their bags. Handschuh remembers

several of the men waving out the back door to him as he took their

pictures. They may have been the last images taken of Rescue One,

who were among the first responders to the scene. Fire Department

officials have confirmed there are thirteen dead of Rescue One’s

twenty-five members, including two officers.

Handschuh,

a staff photographer for The Daily News, was scheduled to teach a

graduate class in photojournalism at NYU in the morning, and cover

late election results at night for the News. While cruising around

Manhattan’s West Side on his way to class, he heard voices from

Manhattan Fire on the scanner screaming to send every piece of apparatus

available to the World Trade Center. As W. 43rd Street’s Rescue

One rushed southbound, Handschuh swerved across the traffic island

on the West Side Highway, and followed them on their rear bumper,

observing their preparations as they threw on their packs, readied

their oxygen tanks, and placed tools in their bags. Handschuh remembers

several of the men waving out the back door to him as he took their

pictures. They may have been the last images taken of Rescue One,

who were among the first responders to the scene. Fire Department

officials have confirmed there are thirteen dead of Rescue One’s

twenty-five members, including two officers.

With massive destruction looming ninety floors up, people on the street

did not yet seem to be conscious of the horror unfolding above them.

“It was eerie and quiet,” said Handschuh, describing the

moments after he arrived, just before the second plane slammed into

the south tower. “People were coming to work with their coffee

and danish, just standing and watching. You could hear the flames

crackling, glass breaking, you could hear things falling. But it was

like someone had turned the volume off on the usual hubbub of the

city, like someone had hit the mute button.”

Handschuh

himself had no inkling of the danger he was in until several moments

later. “I had no idea I would be running for my life as a 110

story building was bombed by terrorists,” he said. Turning his

lens on the flaming tower, Handschuh realized that not all the debris

falling from the north tower was glass and metal. “I couldn’t

begin to describe what it looked like,” he said, referring to

people who appeared at the windows and in desperation began to jump

to their deaths rather than be burned alive, a sight and sound Handschuh

says he will never forget. He has no recollection of making the picture

that appeared in the Daily News, a photograph taken moments after

the second plane hit the south tower. Standing directly underneath

the World Trade Center, the photograph is framed by an achingly beautiful

blue sky as an ominous black cloud of smoke billows out, and a brilliant

orange fireball at the top spews glass and melting steel to the ground.

Handschuh

himself had no inkling of the danger he was in until several moments

later. “I had no idea I would be running for my life as a 110

story building was bombed by terrorists,” he said. Turning his

lens on the flaming tower, Handschuh realized that not all the debris

falling from the north tower was glass and metal. “I couldn’t

begin to describe what it looked like,” he said, referring to

people who appeared at the windows and in desperation began to jump

to their deaths rather than be burned alive, a sight and sound Handschuh

says he will never forget. He has no recollection of making the picture

that appeared in the Daily News, a photograph taken moments after

the second plane hit the south tower. Standing directly underneath

the World Trade Center, the photograph is framed by an achingly beautiful

blue sky as an ominous black cloud of smoke billows out, and a brilliant

orange fireball at the top spews glass and melting steel to the ground.

If the desire to flee in life threatening situations is strong, the

desire to stay and document them for news photographers, is often

stronger. While Handschuh stayed long enough to take some pictures,

at some point his instincts kicked in. “Time stood still,”

he said, as he looked up to see the south tower begin to disintegrate,

accompanied by noises that he said sounded like high pressure gas

explosions. “My initial reaction was to grab my camera, to start

taking pictures,” he said, “but in the back of my mind I

heard a voice that said: ‘run, run, run, run.’ I’ve

been doing this for 20 years and I’ve never run.” He is

convinced that listening to that voice saved his life.

Still photographer Bill Biggart and Glenn Petit, a cameraman for the

NYPD were not as fortunate. Biggart was killed in the collapse of

the towers and Petit is missing and presumed dead. Moments earlier,

Handschuh had run into Petit who told him he had “unbelievable

footage.” Of that moment, Handschuh said: “We gave each

other a hug and said ‘be careful,’ as Glenn ran east, and

was not seen again.”

Handschuh escaped with his life but was seriously injured. Describing

the vortex that swept him up in the collapse of the south tower, he

said: “The wind that picked me up was like getting hit in the

back by a wave at the beach that was made of hot gravel, like being

picked up by a tornado. All of a sudden I was flying, with no control

over direction.” He did not lose consciousness, but he was thrown

a full city block by the force of the implosion, landing underneath

a vehicle, trapped by debris, which crushed his leg, breaking it in

three places. Three firefighters rescued him, taking him to a delicatessen

near Battery Park City, only to be caught underneath the deli’s

caved in façade when the second tower collapsed. “There

were grown men inside, holding onto each other for their lives, some

calm, some screaming with just the desire to live, pushing their way

out of the debris.”

Shortly afterward, fellow Daily News photographer Todd Maisel photographed

Handschuh’s rescue by a paramedic, a cop and a firefighter as

they removed him to a police boat on the Hudson. Although Handschuh

lost his glasses, cell phone and pager, he managed to hold onto his

cameras until shortly before he was transported to Ellis Island on

a police boat. “There we were,” said Handschuh, “under

the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, breathing, entire huddled masses,

yearning to break free, the smoke from the destruction, a symbol of

New York, a symbol of the United States, a symbol of the American

economic system in ruins…And I didn’t have a camera.”

-----------------------------------

New York City’s news photographers were on their mark on September

11. There is no lack of apocalyptic imagery of suicidal bombers hitting

their targets. In stunning images of almost architectural grandeur,

there is Steve Ludlum’s perfectly composed image of twin monoliths,

breathing dragons of fire, with the Brooklyn Bridge as a defining

element in the foreground, an image which appeared on the front page

of the New York Times on September 12. There is Lyle Owerko’s

photograph, which appeared on the cover of Time’s September 11

special issue, taken at virtually the same moment, from the west side,

underneath the towers. In Washington, D.C. there is Jim Lo Scalzo’s

image of the Capitol shrouded in fog from the burning Pentagon in

the foreground. In what at first glance appear to be stills from a

Hollywood special effects movie, there are Robert Clark’s series

of four horizontal images taken shortly after the first impact. Against

a perfectly blue sky, as the north tower burns in the first image,

a menacing commercial airliner threatens the south tower in the second,

and in the third and fourth images, the plane slams into the south

tower, creating indelible reminders of vulnerability.

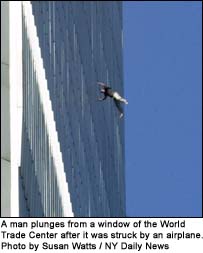

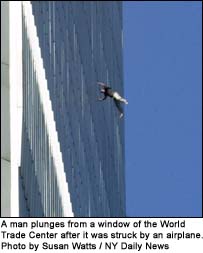

As

photographers focused on the heavily damaged towers, there was a sense

of unreality to the attacks. The towers no longer seemed invincible

but down on the ground, camera lenses began focusing on the human

dimension, the impact of which was not yet fully comprehended. As

people leapt to their deaths from the burning towers, photographers

’s Richard Drew/AP and The Daily News’ Susan Watts made

those images, necessary to the telling, and controversial in their

publication. Some editors came under fire for reproducing images that

depicted such immense suffering. Drew’s image of a man in an

upside-down free fall, juxtaposed against the tower, almost looks

like he could have been tethered to a bungee cord. Sadly, he was not.

As

photographers focused on the heavily damaged towers, there was a sense

of unreality to the attacks. The towers no longer seemed invincible

but down on the ground, camera lenses began focusing on the human

dimension, the impact of which was not yet fully comprehended. As

people leapt to their deaths from the burning towers, photographers

’s Richard Drew/AP and The Daily News’ Susan Watts made

those images, necessary to the telling, and controversial in their

publication. Some editors came under fire for reproducing images that

depicted such immense suffering. Drew’s image of a man in an

upside-down free fall, juxtaposed against the tower, almost looks

like he could have been tethered to a bungee cord. Sadly, he was not.

Yet for all the long lens images that suggested what was happening

at a distance, there were images in which the photographers’

proximity to suffering told a profoundly personal story: that this

was painfully close to home, images in which survivors’ eyes

or body language revealed what they might have been feeling, or thinking

at that moment. Stan Honda’s unforgettable photograph of a woman

coated with the pulverized remains of the World Trade Center, shrouded

by a cloud of otherworldly toxic yellow dust. She stares directly

at the camera in confusion and supplication. Perhaps even defiantly,

she seems to ask: “Do you understand this? Because I simply do

not.”

Shannon Stapleton photographed a mortally wounded Father Mychal Judge,

chaplain of the New York City Fire Department, who died as debris

collapsed on him, shortly after giving last rites to a firefighter.

The peaceful look on Father Judge’s face belies the surrounding

mayhem and the anguished look on the five men’s faces who are

carrying him out of the debris. Honda and Stapleton’s images

have an intimate human dimension to them, in a way that Ludlum’s

and James Nachtwey’s images, respectively, of the collapse of

the towers and the ethereal remains of the World Trade Center, now

known as Ground Zero, speak to the enormity of the physical dimension.

Also at eye level, are the following memorable images: Angel Franco’s

close-up of women reacting to the horror on the street, one woman

with her fist clutched tightly up to her face, the other covering

her eyes in disbelief; Daniel Shanken’s photograph of people

fleeing their city over the Brooklyn Bridge, surrounded by an almost

palpable thickness of gray ash and dust, one can almost feel its weight;

Todd Maisel’s photograph of weary firefighters on top of the

rubble with eerie remnants of steel beams as memorial at Ground Zero;

Justin Lane’s image of a man being triaged by firefighters and

EMT’s with an exhausted firefighter leaning against the subway

entrance. It looks like the end of the world; Suzanne Plunkett’s

image of the dust cloud chasing terrified pedestrians as the towers

fell; Ruth Fremson’s woman in red: red hair, red dress, her limbs

bloodied from injuries, sitting on a sidewalk, terrified, startled,

fragile; Catherine Leuthold’s photograph of a determined rescue

worker whose eyes and face are encrusted with ash, with what appears

to be a tear streaming down his face; Susan Watts’s photograph

of a dazed man whose shirt is caked with blood, being aided by a man

on a cell phone; Amy Sancetta’s photograph of a businessman and

woman carrying briefcases covered in dust and ash, fleeing the capitalist

marketplace, as if in subjugation to the terrorists’ unspoken

goals. If there is defiance in some of the photographs, there seems

to be resignation and abject fear in others.

These images confirmed America’s worst fears: that what was lost

were not simply American icons reduced to rubble; but rather what

Americans held most dear: mothers and fathers, sisters, brothers,

aunts, uncles, children, and, if you will, innocence. Photographers

used to being the ultimate observers, perhaps for the first time,

found that it was impossible to separate themselves from the story.

The emotional distance photographers have often called upon to maintain

a feeling of objectivity for their stories, disappeared along with

the thousands of other victims in the wake of the tragedy.

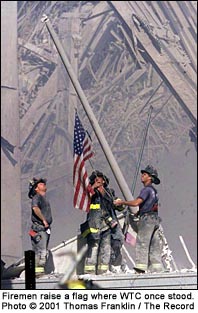

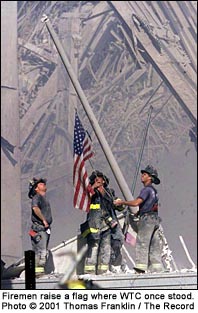

At

a time when Americans needed a small sign of hope, Thomas Franklin,

staff photographer at The Record in Bergen County, NJ provided an

image that is already being compared to Joe Rosenthal’s photograph

of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, an image that Franklin made

of three New York City firefighters raising the American flag on Ground

Zero. Franklin, who has received thousands of phone calls and hundreds

of emails, “mostly from complete strangers around the world"

telling him what the photograph means to them, said he is hopeful

that money can be raised from the sale of the photograph to help victims.

“That speaks to me about the immense power of photojournalism,”

he said.

At

a time when Americans needed a small sign of hope, Thomas Franklin,

staff photographer at The Record in Bergen County, NJ provided an

image that is already being compared to Joe Rosenthal’s photograph

of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, an image that Franklin made

of three New York City firefighters raising the American flag on Ground

Zero. Franklin, who has received thousands of phone calls and hundreds

of emails, “mostly from complete strangers around the world"

telling him what the photograph means to them, said he is hopeful

that money can be raised from the sale of the photograph to help victims.

“That speaks to me about the immense power of photojournalism,”

he said.

Photographers attempting to document the attacks confronted more obstacles

than debris and the cyclone fence that was eventually constructed

around the fallen towers. Not only did they meet with some of the

typical resistance from the New York City Police Department, but some

were arrested for criminal trespass as well, leading some to speculate

if press credentials were worth having. The first few days were so

chaotic that anyone who wanted to find a way into the site to photograph,

could do it with a little persistence. Carolina Salguero, a photographer

whose work was published in The New York Times Magazine on both September

16 and September 24, managed to get to Ground Zero relatively quickly

the first day by coming over in her boat from Brooklyn. But as time

wore on, access to the site became more difficult as the Police department

and National Guard threatened anyone with media credentials with arrest

even if they took pictures from behind the fence. While there was

an understandable need for FEMA and the NYPD to secure the area, the

public seemed to have as much access as those with legitimate media

credentials, angering many photographers and forcing some of them

to find creative ways of getting to the site. Some photographers were

reported to have impersonated firefighters and construction workers,

leading to dozens of arrests of media personnel by the NYPD. Many

photographers have voiced loud opposition to photographers who misrepresented

themselves, ultimately making it more difficult for those who used

legitimate means and current credentials to get their pictures. Unfortunately

for many who went through DCPI channels, getting close to the site

meant waiting hours to perhaps get only a block or two closer than

the so called “media villages” established by the NYPD.

Although closure seems elusive for Americans in general and New Yorkers

in particular, photographers who were involved in covering the World

Trade Center attacks, have expressed anguish about the people they

have photographed and the stories they have covered. New York Times

staff photographer Ruth Fremson, who was stationed in Jerusalem for

the Associated Press before coming to the Times, has seen destruction

on a massive scale, but “never at a moment when so many people

were destroyed.” Like David Handschuh, Fremson was caught in

the tidal wave of the two buildings’ demise but emerged uninjured.

She said she is haunted by pictures she took, of people helping others,

not knowing the outcomes of some of the rescue efforts. Fremson received

a phone call from the parents of the woman in red who appeared on

the front page of the New York Times, updating her on their daughter’s

progress. “Knowing that people are safe is a huge relief,”

she said.

In a twist of irony, Washington Post photographer Michael Williamson

found the tables turned on him while covering the emotional stories

of people searching for missing loved ones. “I was talking to

a woman who told me the story of being on the cell phone with her

daughter when her daughter died; her daughter couldn’t breathe,

and then silence because the building collapsed,” he said. “I

just started crying, and then another photographer photographed me

thinking I’d lost someone. I was just upset for all these people

who have lost loved ones,” he said.

Photographers have been profoundly affected by the World Trade Center

attacks. Veteran New York Times staff photographer Angel Franco, who

was in Kuwait, and who has seen smart bombs and terror overseas, worries

that none of the young photographers who have covered the events of

the past few weeks are prepared for the emotional fallout that will

follow. “None of them is combat trained,” he says.

Freelance photographer Aaron Lee Fineman, who was assigned by the

New York Times to take pictures on the night of the attacks, spent

from 9pm until early the next morning documenting rescue efforts amidst

the rubble. His photograph of workers moving wreckage during a rescue

effort, ran on the front page of the New York Times on September 13.

During the night, he was grazed on the back of his head by falling

debris and his digital camera was slightly damaged. Fineman voiced

concerns as a freelancer who pays for his own health and equipment

insurance, a not insignificant consideration for a person who risked

his life in the pursuit of his job. Assigned to return the following

night, he initially said yes, but then had a change of heart and decided

to turn down the assignment. Finding the experience turbulent, Fineman

said: “I have this vivid picture that I haven’t been able

to shake out of my head, of bodies beneath the wreckage. It was too

much for me the first time.” Fineman credits Angel Franco, who

has spent time talking to Fineman, with helping him to get through

some of the trauma.

The conflict of whether to stay or to get closer was described most

poignantly by Helayne Seidman, a freelance photographer who works

for the New York Post. “I was shooting on Broadway near Fulton

Street,” she says in her contribution to ‘Voices.’

“My first thought was, ‘Should I stay or should I run?’

I instinctively ran from the dust ball because I could not breathe.

I feared the other tower might collapse, so I covered the exodus of

people, rather than going back closer. The conflict of whether I should

have gone back has haunted me all week.” Surely Seidman made

the right choice, but the need, as a journalist to get images that

were in some ways not only difficult to make, but in some cases under

life threatening circumstances, have made photographers ask themselves

many questions: Why did I survive when so many others didn’t?

Why didn’t I get the pictures when I had the opportunity? Why

wasn’t I there? There were many photographers who for personal

or professional reasons, were unable to cover the story and are having

a hard time dealing with not having gotten images from perhaps the

biggest story New York has ever seen, a trite quandary, to be sure,

when compared to life’s bigger issues of life and death, but

one with which many are nonetheless grappling.

The

visual testimony of photographers who have worked on this story has

been remarkable. But for many, the tears are just below the surface.

Mel Evans, a staff photographer for The Record, in Bergen County,

New Jersey says he’s done “much better working than not,”

but says when he arrives home at night he hugs his daughter just a

little tighter. Shannon Stapleton, chokes back tears when he thinks

of the photograph he took of Father Judge being removed from the rubble.

But he takes some solace from a letter he received from Judge’s

family thanking him for taking such a compassionate photo, telling

him: “It helps to know that he died doing what he loved best,

helping his beloved firemen and the citizens of New York City.”

Stapleton says he is heartened knowing that a photo could have a positive

impact amidst such horrific destruction.

The

visual testimony of photographers who have worked on this story has

been remarkable. But for many, the tears are just below the surface.

Mel Evans, a staff photographer for The Record, in Bergen County,

New Jersey says he’s done “much better working than not,”

but says when he arrives home at night he hugs his daughter just a

little tighter. Shannon Stapleton, chokes back tears when he thinks

of the photograph he took of Father Judge being removed from the rubble.

But he takes some solace from a letter he received from Judge’s

family thanking him for taking such a compassionate photo, telling

him: “It helps to know that he died doing what he loved best,

helping his beloved firemen and the citizens of New York City.”

Stapleton says he is heartened knowing that a photo could have a positive

impact amidst such horrific destruction.

Photographers can be proud of their work documenting history over

the past few weeks. But David Handschuh, now recovering at home after

surgery, urges them to be mindful and take a few minutes to assess

their psychological well being after witnessing the attacks. He says

it is not normal to see the kind of horror that many experienced first-hand

while on the job.

“Whether it means talking to a friend, clergyman, psychologist

or psychiatrist, it may be necessary to get some kind of stress debriefing,”

he says, adding that the outpouring of support from friends and colleagues

in visits, phone calls and emails have raised his spirits and helped

enable him to move forward. He acknowledges that although newspeople

often find it easier to talk to a colleague, at least initially, it

is not unusual for peer support to act as a springboard for clinical

support where needed. Two years ago, the NPPA, of which Handschuh

is past president, conducted a survey of about the effect on newspeople

of covering traumatic situations in doing their work and found it

was not unusual for visual journalists to suffer negative effects

from the cumulative exposure of repeatedly documenting the news. Newscoverage

Unlimited, a not-for-profit organization established in 1999, is working

together with NPPA on this initiative to assist visual journalists

in fostering mutual support through trained peer counselors. They

are in the process of setting up a New York office and a nationwide

support network to deal with the problems that will undoubtedly resonate

for a long time as a result of the World Trade Center attacks. For

peer support and information, journalists in need of support may wish

to contact NPPA/Newscoverage Unlimited at 911@newscoverage.org

or to get a complete list of trained peer counsellors that journalists

can call with issues relating to work related traumas, go to: http://www.nppa.org/wtc/help.html.

For general information as to how news organizations and individuals

can volunteer and support their ongoing efforts, contact info@newscoverage.org.

The Dart Center also has a message board set up for journalists who

have experienced trauma in their work at www.dartcenter.org.

Photographer David Handschuh is taking things one day at a time. People

have asked if he intends to keep on taking pictures and his answer

is “probably, yes.” He insists that “we will get over

this,” adding “we will be changed in ways that we never

imagined. But we will be stronger and more tolerant. Just looking

out the window at the blue sky makes me happy. I am here.”

Susan B. Markisz

October 1, 2001

At

8:46 a.m. the ordinary became the extraordinary as voices over police

and fire scanners reported ominous sounding information of what was

first assumed to be an errant private plane hitting the north tower

of the World Trade Center. Moments later came terrifying details of

a second plane, a commercial airliner slamming into the south tower,

sending photographers into combat mode, scrambling to find the quickest

route downtown. Within minutes, photographers who had made their way

to the scene, found themselves in mortal danger along with firefighters,

police and rescue workers. Within the hour, photographers were wiping

away tears, while at the same time producing stunningly surreal images,

destined to become embedded in our national collective psyche. By

the end of the day, the New York primary had become a footnote---history

deferred---to an ignominious terrorist attack on New York City’s

World Trade Center, leaving more than 5,000 dead or missing, and injuring

thousands more.

At

8:46 a.m. the ordinary became the extraordinary as voices over police

and fire scanners reported ominous sounding information of what was

first assumed to be an errant private plane hitting the north tower

of the World Trade Center. Moments later came terrifying details of

a second plane, a commercial airliner slamming into the south tower,

sending photographers into combat mode, scrambling to find the quickest

route downtown. Within minutes, photographers who had made their way

to the scene, found themselves in mortal danger along with firefighters,

police and rescue workers. Within the hour, photographers were wiping

away tears, while at the same time producing stunningly surreal images,

destined to become embedded in our national collective psyche. By

the end of the day, the New York primary had become a footnote---history

deferred---to an ignominious terrorist attack on New York City’s

World Trade Center, leaving more than 5,000 dead or missing, and injuring

thousands more. Handschuh,

a staff photographer for The Daily News, was scheduled to teach a

graduate class in photojournalism at NYU in the morning, and cover

late election results at night for the News. While cruising around

Manhattan’s West Side on his way to class, he heard voices from

Manhattan Fire on the scanner screaming to send every piece of apparatus

available to the World Trade Center. As W. 43rd Street’s Rescue

One rushed southbound, Handschuh swerved across the traffic island

on the West Side Highway, and followed them on their rear bumper,

observing their preparations as they threw on their packs, readied

their oxygen tanks, and placed tools in their bags. Handschuh remembers

several of the men waving out the back door to him as he took their

pictures. They may have been the last images taken of Rescue One,

who were among the first responders to the scene. Fire Department

officials have confirmed there are thirteen dead of Rescue One’s

twenty-five members, including two officers.

Handschuh,

a staff photographer for The Daily News, was scheduled to teach a

graduate class in photojournalism at NYU in the morning, and cover

late election results at night for the News. While cruising around

Manhattan’s West Side on his way to class, he heard voices from

Manhattan Fire on the scanner screaming to send every piece of apparatus

available to the World Trade Center. As W. 43rd Street’s Rescue

One rushed southbound, Handschuh swerved across the traffic island

on the West Side Highway, and followed them on their rear bumper,

observing their preparations as they threw on their packs, readied

their oxygen tanks, and placed tools in their bags. Handschuh remembers

several of the men waving out the back door to him as he took their

pictures. They may have been the last images taken of Rescue One,

who were among the first responders to the scene. Fire Department

officials have confirmed there are thirteen dead of Rescue One’s

twenty-five members, including two officers. Handschuh

himself had no inkling of the danger he was in until several moments

later. “I had no idea I would be running for my life as a 110

story building was bombed by terrorists,” he said. Turning his

lens on the flaming tower, Handschuh realized that not all the debris

falling from the north tower was glass and metal. “I couldn’t

begin to describe what it looked like,” he said, referring to

people who appeared at the windows and in desperation began to jump

to their deaths rather than be burned alive, a sight and sound Handschuh

says he will never forget. He has no recollection of making the picture

that appeared in the Daily News, a photograph taken moments after

the second plane hit the south tower. Standing directly underneath

the World Trade Center, the photograph is framed by an achingly beautiful

blue sky as an ominous black cloud of smoke billows out, and a brilliant

orange fireball at the top spews glass and melting steel to the ground.

Handschuh

himself had no inkling of the danger he was in until several moments

later. “I had no idea I would be running for my life as a 110

story building was bombed by terrorists,” he said. Turning his

lens on the flaming tower, Handschuh realized that not all the debris

falling from the north tower was glass and metal. “I couldn’t

begin to describe what it looked like,” he said, referring to

people who appeared at the windows and in desperation began to jump

to their deaths rather than be burned alive, a sight and sound Handschuh

says he will never forget. He has no recollection of making the picture

that appeared in the Daily News, a photograph taken moments after

the second plane hit the south tower. Standing directly underneath

the World Trade Center, the photograph is framed by an achingly beautiful

blue sky as an ominous black cloud of smoke billows out, and a brilliant

orange fireball at the top spews glass and melting steel to the ground.

As

photographers focused on the heavily damaged towers, there was a sense

of unreality to the attacks. The towers no longer seemed invincible

but down on the ground, camera lenses began focusing on the human

dimension, the impact of which was not yet fully comprehended. As

people leapt to their deaths from the burning towers, photographers

’s Richard Drew/AP and The Daily News’ Susan Watts made

those images, necessary to the telling, and controversial in their

publication. Some editors came under fire for reproducing images that

depicted such immense suffering. Drew’s image of a man in an

upside-down free fall, juxtaposed against the tower, almost looks

like he could have been tethered to a bungee cord. Sadly, he was not.

As

photographers focused on the heavily damaged towers, there was a sense

of unreality to the attacks. The towers no longer seemed invincible

but down on the ground, camera lenses began focusing on the human

dimension, the impact of which was not yet fully comprehended. As

people leapt to their deaths from the burning towers, photographers

’s Richard Drew/AP and The Daily News’ Susan Watts made

those images, necessary to the telling, and controversial in their

publication. Some editors came under fire for reproducing images that

depicted such immense suffering. Drew’s image of a man in an

upside-down free fall, juxtaposed against the tower, almost looks

like he could have been tethered to a bungee cord. Sadly, he was not. At

a time when Americans needed a small sign of hope, Thomas Franklin,

staff photographer at The Record in Bergen County, NJ provided an

image that is already being compared to Joe Rosenthal’s photograph

of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, an image that Franklin made

of three New York City firefighters raising the American flag on Ground

Zero. Franklin, who has received thousands of phone calls and hundreds

of emails, “mostly from complete strangers around the world"

telling him what the photograph means to them, said he is hopeful

that money can be raised from the sale of the photograph to help victims.

“That speaks to me about the immense power of photojournalism,”

he said.

At

a time when Americans needed a small sign of hope, Thomas Franklin,

staff photographer at The Record in Bergen County, NJ provided an

image that is already being compared to Joe Rosenthal’s photograph

of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, an image that Franklin made

of three New York City firefighters raising the American flag on Ground

Zero. Franklin, who has received thousands of phone calls and hundreds

of emails, “mostly from complete strangers around the world"

telling him what the photograph means to them, said he is hopeful

that money can be raised from the sale of the photograph to help victims.

“That speaks to me about the immense power of photojournalism,”

he said. The

visual testimony of photographers who have worked on this story has

been remarkable. But for many, the tears are just below the surface.

Mel Evans, a staff photographer for The Record, in Bergen County,

New Jersey says he’s done “much better working than not,”

but says when he arrives home at night he hugs his daughter just a

little tighter. Shannon Stapleton, chokes back tears when he thinks

of the photograph he took of Father Judge being removed from the rubble.

But he takes some solace from a letter he received from Judge’s

family thanking him for taking such a compassionate photo, telling

him: “It helps to know that he died doing what he loved best,

helping his beloved firemen and the citizens of New York City.”

Stapleton says he is heartened knowing that a photo could have a positive

impact amidst such horrific destruction.

The

visual testimony of photographers who have worked on this story has

been remarkable. But for many, the tears are just below the surface.

Mel Evans, a staff photographer for The Record, in Bergen County,

New Jersey says he’s done “much better working than not,”

but says when he arrives home at night he hugs his daughter just a

little tighter. Shannon Stapleton, chokes back tears when he thinks

of the photograph he took of Father Judge being removed from the rubble.

But he takes some solace from a letter he received from Judge’s

family thanking him for taking such a compassionate photo, telling

him: “It helps to know that he died doing what he loved best,

helping his beloved firemen and the citizens of New York City.”

Stapleton says he is heartened knowing that a photo could have a positive

impact amidst such horrific destruction.