|

|

|

|

|

STILL BUILDING TOWARD AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

by Greg Smith

The construction continues here at the Last Resort.

As noted last month, despite fears for the future, I'm building. You could say I've spent the past few weeks on little else.

My construction sites include our aging dock in the river, a book under contract from UNC Press and efforts to improve the future of photojournalism, or at least, publication photography in general.

My major effort was hosting a fall meeting of ASMP/South Carolina. I serve on the state board for the American Society Of Media Photographers , and in that role, I must host one of our Quarterly Gatherings each year. Overly ambitious, I volunteered to serve an oyster roast (gathering the oysters myself from the mud near my home) on a Friday night, followed by a business seminar the next day. The former aimed to build relationships, the latter to reinforce our collective strength in the marketplace.

| I also hoped the gathering - to which we invited all photographic professionals - might aid efforts to create and educate a local photographer's roundtable. Working with another ASMP member, who also hosted Saturday's estimating seminar at his nearby Savannah, Ga., studio, I've tried to get a group together to meet, talk and listen the second Monday of each month. Our market crosses a state line and includes coastal islands with road systems that are effectively big cul de sacs. Hence, we're a spread out bunch, some of us 80 miles apart by road (while only 8 miles by seagull). That may account for the fact we've only averaged a dozen folks at each of four meetings, out of a mailing list of four times that number. Still, we have attracted precious few of the most visible photographers in our area. |

|

I suspect these folks just don't see a value in getting together each month. Perhaps they fear losing a competitive edge. But the reality is our market, composed mostly of portrait photographers who shoot commercial and editorial on the side, generates rates and rights packages way below the national averages in these categories. As a resort area, we also harbor a plethora of "trustfunders" (offspring of the rich) with cameras, as well as retirees who can finally get serious about their hobby. They don't need to make a living, but they love photography. Some are even good. But most don't charge full freight for their work. The sheer numbers of such folks makes our local professional photography scene appear unprofessional. Rates are low. Rights aren't discussed. And experts come from out of town.

Nevertheless, each of the weekend's events attracted about two-dozen photographers, most ASMP members, but a few of my local comrades, too. One joined ASMP on Saturday. And all walked away better for the experience(s). I don't know how this will translate into building our market and our relationships, but some roads are worth walking, even if you don't know for sure where they lead.

FIXIN' AND MIXIN'

Three years ago, by a linking of acquaintances, I met Sallie Ann Robinson Coleman. Sallie is the descendent of freed slaves who settled on Daufuskie Island, a 5- x 2.5-mile sand bar with trees across Calibogue Sound from Hilton Head Island, and not far from here. The island has never had a bridge, and it has been one of the few homes to unique culture and dialect descended from slave times and known as "Gullah." In 1969, Pat Conroy, a young writer, schoolteacher and the son of a marine fighter pilot who grew up in nearby Beaufort, S.C., came to the island to teach. His experiences resulted in the best-selling novel "The Water Is Wide," and inspired the movie "Conrack." Conroy also changed 11-year-old Sallie's life.

|

She was reared in a pre-industrial Gullah world where Motown played on the radio and going to the grocery store was an all-day journey, involving an ox cart, boats and arranged rides "on the other side." Along with her sisters, mother, stepfather and extended family, she learned to grow, gather, catch, kill and prepare nearly every meal. Now, at age 43, she is a mother of four, grandmother of three, she lives in Savannah and she works as a certified nurse assistant, providing private care for the aged and dying. Sallie is an amazing person, my dear friend and my partner in writing a cookbook that details how her family lived and cooked. |

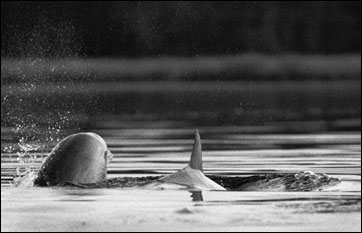

This past month, after several years of submissions and negotiations, the University of North Carolina Press issued an advance contract (to be followed by a small advance fee) for us to complete her book: "Daufuskie Home Cooking: Fixin' and Mixin' Down Yondah." We have a deadline of mid-February. The book will include 100 recipes in eight sections, bearing titles such as "The Woods," "The Yard," "The Garden" and "The Sea." Some 30 recipes will include stories about how the experiences associated with acquiring and preparing the meal. I will provide 25 black-and-white images of the island, much of which has become a resort for the very rich, that I hope will give a sense of the food and the people who serve(d) it.

The book will be a key focus for me in coming months, rather than a part-time diversion. It's a tough balance: to blend in enough Gullah for the island's flavor to come through, while not confusing the reader; to employ my best skills as a communicator while maintaining Sallie's voice; to tell our tales, while still producing a very practical cooking guide; to make pictures that give a sense of the food and place, without focusing on dishes of food, which don't look that good in monotone; and to continue my business and life while investing in the hope for some royalties down the road.

Look for us to be pitching the book on Oprah Winfrey in 2003.

THE DOCK

As explained before, I live on a tidal river, in a small house my second brother and I built beside my mother's home some 15 years back. I've reared two sons here and I'm halfway through rearing a smart, beautiful daughter. The two homes sit on three, wooded acres, which given the rapid development around us, have become quite valuable.

But in the late 1970s, this land was very affordable. My father, who earned a modest living as a research scientist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, on retirement, traded our suburban Washington home for a three-acre lot on the May River. He scraped up enough money 20 years ago to build a modest house, moved down here, and within months, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Nevertheless, while he was sick, plans continued to build a 230-foot dock to the shallow channel of the river. He and I watched the dock being built, and even enjoyed fishing from it a few times.

But 20 years took its toll on the rough-sawn planks and railings. For my mother's 80th birthday this past February, both of my brothers, their wives, my sister, myself and several of our offspring converged on the dock, redecked the walkway and replaced the railings. We didn't get to fixing the floating dock, nor the ramp that leads to it.

| My oldest brother, in a manic mood, showed up last week, just as I came down with a cold and completed the huge effort of hosting our ASMP gathering. His goal was to finish the job. And I was thrown right into a huge project of pulling up old boards and creatively configuring new, wet, heavy 2-inch-thick, treated lumber to replace them. Somehow I have survived. And now we have a spiffy new floating dock for mooring our decrepit skiff, tying off our crab traps and launching our kayaks. The railings on the ramp are now sanded smooth; no more splinters. |

|

It was tough week, very hot for October as I sweated through a cold amid sawdust, bruises, splinters and playing a dutiful little brother. But we actually got along pretty well. And one more construction project is complete.

MY BIG MOUTH

Concurrent with all these efforts, I've continued to chime in occasionally on several e-mail lists for photographers and photojournalists. One of my latest such essays appeared on the Editorial Photographer's List .

In last month's journal here, I alluded to the plight of Jonathan Barth, a New York freelancer who used to sell images through Getty's Liaison agency. He made pictures on Sept. 11, and eventually transmitted some to Getty, where editors decided they wanted to use two pictures on their self-service stock web site.

Barth had a contract with Liaison that stated he received 50 percent of each sale, but for use on this web site, Getty editors demanded a "buyout" (or work for hire) of all rights to the images for a rather low fee. Barth responded by posting his tale on the EP list. Subsequently, his relationship with Getty was severed.

Richard Ellis, a former photographer who manages Liaison for Getty is one of the few members of the private EP List who is an agent. Many called on the list for him to explain his side of what happened. One of the list's moderators contacted Ellis, who apparently isn't allowed by Getty Images to post his own opinions. The moderator, a well-known and respected photojournalist and commercial shooter, reported that Getty believed Barth had acted unprofessionally by taking his complaints public. And, the moderator (whom I am not naming, because EP is a private list) noted, we need to understand that Getty is in the business of maximizing profits.

I replied: