|

Dispatches

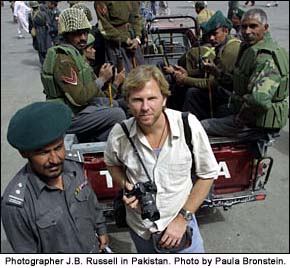

- J.B. Russell in Pakistan

|

America's

New War on Terrorism Finally Begins America's

New War on Terrorism Finally Begins

President George Bush says that some of this new, first war of the 21st

century will be seen and some of it won't. For those of us who jumped

on the first plane to Pakistan in the initial days after the terrorist

attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it has been a long

wait for the visual part of this war to begin. Even if now that it has

begun, no one can see it.

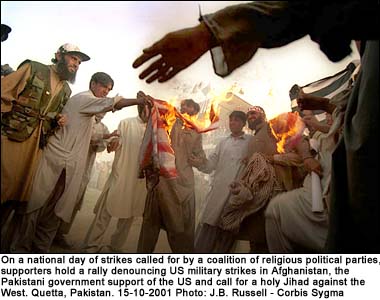

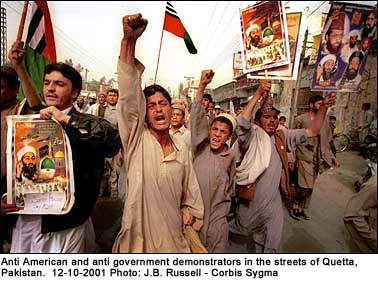

ince landing in Islamabad and coming to the dusty, isolated, southwestern

town of Quetta a month ago, the standard photographic fare has been

the demonstrations and rallies held several times a week by Pakistan's

extremist religious political parties that support the Taliban and Osama

bin Laden in Afghanistan. These protests have been very volatile and

visual, somewhat akin to a revival meeting, but like the religious far

right in the US, these parties and their followers are a boisterous

minority in Pakistan. Hundreds of people gather, various Mullahs yell

the standard anti American insults and the twisted islamic extremist

propaganda. The crowd, at regular intervals get up, scream Allah-o-akbar

and wave banners and images of Osama bin Laden. Then for the grand finale

the Mullahs call for a holy Jihad, the obligatory effigy of George Bush

and several American flags are burned, everyone goes ape shit and then

they go home. After covering numerous of these rallies they seem to

become theatrical. However Afghanistan, where the real story is being

played out is off limits and out of sight.

Baluchistan, where Quetta is located, is a remote, arid corner of southwestern

Pakistan near the Afghan border. It is dominated by tribal areas with

a reputation for violence and smuggling. Due to the tenuous situation,

local authorities require all forgein journalists to be escorted by

an armed guards in order to protect "our valued guests." Although

a bit inconvenient at times, it did not pose much of a problem during

the past few weeks as I covered the demonstrations, did stories on the

building refugee crisis, the Madrasa islamic schools from which the

Taliban movement was born, the problems of drug addiction on the doorstep

of the worlds largest exporter of heroin and a variety of stories in

this checkered town.

When

the reprisal bombings finally started the demonstrations here in Quetta

suddenly turned violent. Our hosts immediately locked down the hotel

compound effectively detaining the entire press corps under house arrest

in a four star prison. As demonstrators rampaged through the town burning

several banks, two cinemas that show American movies and the UNICEF

office, the police officers at the hotel found themselves fending off

a rebellion of journalists attempting to escape the hotel in order to

do their jobs. In frustration at the end of the day, several of us rushed

the guards en masse and jumped the hotel wall. This created quite a

scene, but allowed us to negotiate an escorted tour of the rampage aftermath. When

the reprisal bombings finally started the demonstrations here in Quetta

suddenly turned violent. Our hosts immediately locked down the hotel

compound effectively detaining the entire press corps under house arrest

in a four star prison. As demonstrators rampaged through the town burning

several banks, two cinemas that show American movies and the UNICEF

office, the police officers at the hotel found themselves fending off

a rebellion of journalists attempting to escape the hotel in order to

do their jobs. In frustration at the end of the day, several of us rushed

the guards en masse and jumped the hotel wall. This created quite a

scene, but allowed us to negotiate an escorted tour of the rampage aftermath.

The next day, after much negotiation, we managed to leave the hotel

to work. At the end of the day myself and several other photographers

were in Kuchlak, a small town near Quetta, where there had been an incident

earlier in the day. Demonstrators had ransacked the village and attacked

a police post. In the mêlée police shot and killed three

protesters, including a 14 year old boy. As we photographed the families

grieving over the victims, the police who had escorted us there for

our protection suddenly became aggressive and began physically forcing

us to leave. As we retreated, the situation degenerated and the police

forces that had previously been overly concerned about our personal

safety turned violently against us. French photographer Patrick Adventurier

of the Gamma agency and Vincent Laforet of the NY Times were beaten

by the police. Paula Bronstein of Getty images and myself were manhandled

and all of us had equipment damaged.

In the end no one was seriously hurt, but the tension has been turned

up several notches since America's new war on terrorism has begun in

a tangible way. The entire world and the journalists covering these

events are walking a very fine line. Quetta, 10-10-2001

Quetta, Pakistan. 12 October 2001

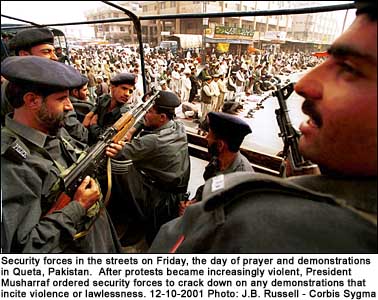

Friday,

the day of prayer in the Islamic world. In Pakistan it is the day of

piousness and then demonstrations. For several weeks now, after Friday

prayers thousands of men have poured out of mosques, whipped into a

frenzy by hard line Mullahs, to protest the anticipated US attacks on

Afghanistan. Today is the first Friday since the US attacks began. Following

the violent demonstrations that took place the day after the first US

bombings, President Pervez Musharraf declared that all demonstrators

that damage property, break the law or incite violence would be shot. Friday,

the day of prayer in the Islamic world. In Pakistan it is the day of

piousness and then demonstrations. For several weeks now, after Friday

prayers thousands of men have poured out of mosques, whipped into a

frenzy by hard line Mullahs, to protest the anticipated US attacks on

Afghanistan. Today is the first Friday since the US attacks began. Following

the violent demonstrations that took place the day after the first US

bombings, President Pervez Musharraf declared that all demonstrators

that damage property, break the law or incite violence would be shot.

From early morning there was a huge security presences in the streets

of Quetta. Military, APCs, heavily armed police forces and even a small

cavalry of policemen on horseback patrolled the streets. Around 2:00

PM the call to prayer echoed from the spires of mosques throughout the

city and the faithful laid down their mats and bowed in worship to Allah

and his prophet Mohammed, all under the watchful eye of the security

forces and the world's media. In a matter of minutes after the prayers

ended, large numbers of young men began to run through the streets yelling

angry protests and waving banners. The crowds swelled and, followed

closely by police, ran toward a large stadium area for an enormous rally.

Several

hours of speeches by a long line of bearded, turbaned Mullahs followed.

Each one denounced the US, its allies, and the government of General

Musharraf. They called for national strikes, volunteers to go fight

along side their Taliban brothers and the inevitable Jihad, or holy

war. As the sun began to set into a dusty haze, the habitual effigy

of President George Bush was descended before the crowd. The handlers

had trouble getting it lit and the crowd couldn't contain themselves.

They beat and ripped the figure to shreds before it could be burnt and

then went wild. Crowds surrounded many of the foreign journalist some

throwing stones and aggressively pushing toward them. The private security

forces of the Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI), the extremist religious political

party that organizes most of the anti American demonstrations, quickly

corralled the journalists and escorted us to our cars. Several

hours of speeches by a long line of bearded, turbaned Mullahs followed.

Each one denounced the US, its allies, and the government of General

Musharraf. They called for national strikes, volunteers to go fight

along side their Taliban brothers and the inevitable Jihad, or holy

war. As the sun began to set into a dusty haze, the habitual effigy

of President George Bush was descended before the crowd. The handlers

had trouble getting it lit and the crowd couldn't contain themselves.

They beat and ripped the figure to shreds before it could be burnt and

then went wild. Crowds surrounded many of the foreign journalist some

throwing stones and aggressively pushing toward them. The private security

forces of the Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI), the extremist religious political

party that organizes most of the anti American demonstrations, quickly

corralled the journalists and escorted us to our cars.

While the demonstration was large and boisterous, it was also very well

organized and contained. Following the same formula that we have seen

for many weeks. Once again, the supporters of these fundamentalist groups

are a small minority in Pakistan. Nevertheless, as the bombings in Afghanistan

continue and demonstrations around the Muslim world become more numerous,

the tension just below the surface is mounting in the delicate coalition

against terrorism.

Another long, tense, dusty day. Now begins many, many hours of transmitting

photos over the totally saturated Pakistani internet servers. Thankfully,

at my hotel with a foreign passport and a signed declaration that I'm

not a Muslim, I can order a cold beer to get me through the night.

Quetta,

Pakistan. 18 October 2001

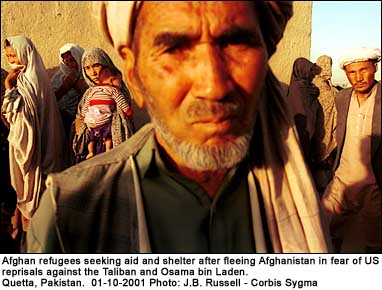

From

the beginning of this crisis humanitarian organizations have warned

of a potentially catastrophic humanitarian disaster looming on the other

side of the border. After more than 20 years of war and four years of

severe drought there are already over 2 million refugees in Pakistan

and many more in other neighboring countries. For most Afghans still

in the country, living conditions were already dire, teetering on widespread

famine. With winter approaching, aid organizations forced to leave the

country and US retaliatory attacks looming overhead, sustainable existence

for Afghans seemed to be pushed over the edge. From

the beginning of this crisis humanitarian organizations have warned

of a potentially catastrophic humanitarian disaster looming on the other

side of the border. After more than 20 years of war and four years of

severe drought there are already over 2 million refugees in Pakistan

and many more in other neighboring countries. For most Afghans still

in the country, living conditions were already dire, teetering on widespread

famine. With winter approaching, aid organizations forced to leave the

country and US retaliatory attacks looming overhead, sustainable existence

for Afghans seemed to be pushed over the edge.

Despite reports of huge numbers of people on the move within the country,

primarily fleeing the cities, large numbers of refugees flooding into

Pakistan failed to materialize. Concerned about yet another wave of

refugees, Pakistan closed its borders. While some refugees did manage

to trickle through the mountains and remote border crossings, they quickly

blended into the local refugee population to avoid being repatriated.

Now that the bombardment of Afghanistan is into its second week and

the city of Kandahar, the Taliban's headquarters just opposite Quetta,

is being heavily targeted we heard that larger numbers of refugees were

crossing the border at Chaman.

After the habitual negotiations with the local security forces, a small

group of journalists managed to arrange an escorted convoy to the Chaman

border post. We set out on the three hour trip across a desolate, arid

landscape to the border. We passed abandoned refugee camps from previous

crises and the smoking chimney towers of brick making kilns. At the

border crossing we once again negotiated with border guards to assure

them that we were authorized to be there and to photograph. We were

able to work for about an hour before being ushered away for the three

hour journey back to Quetta. During the brief stay, we witnessed a steady

stream of Afghans coming into Pakistan. The majority were children and

women, dressed in the traditional burqa required by the Taliban regime.

Burqas cover women from head to toe, rendering them anonymous blue ghosts.

Many men bring their families out of Afghanistan and return to guard

family homes against looting or are forcibly conscripted by the Taliban

to fight against US forces. Despite the fact that the border remains

officially closed, the refugees told us that they paid baksheesh to

the border guards and were allowed to cross the border where they loaded

all their belongings, including livestock sometimes, into the backs

of local pick-up trucks to take them down to Quetta. Those who don't

have the means to get to the border or to buy their way across attempt

to go to relatives in the slightly more secure countryside, but nevertheless

are caught in the crossfire of Taliban repression, draught and the war

on terrorism.

--

J.B. Russell, Photojournalist

e-mail: RoadtoNowhere@compuserve.com

I

am a photojournalist and this is what I do - documenting contemporary

history and critical humanitarian issues. I do it because I love photography,

I think it is imperative that the world is informed and aware about

the condition of humanity on our planet and images are one of the best

ways of conveying this reality to a wider public. I hope that in a small

way my work and the collective work of all journalist will contribute

to better understanding and eventual resolution of the many conflicts

and injustices that exist in our societies. At times this entails considerable

personal and financial risks. Like all independent photographers, especially

in the current economic environment of the editorial world, it is extremely

difficult to make a decent living. However, I've been doing this long

enough and have a good enough relationship with my editors and the magazines

that I can usually make it pay. Noone pursues this profession to make

money though. On the other hand, the experiences that I have and the

people that I meet while doing this work are more valuable and add more

personal wealth to my life than any potential financial rewards could

ever provide. Perhaps I'm crazy, but I think it's worth it. I'd like

to thank Kodak France for generously providing the film for this project. I

am a photojournalist and this is what I do - documenting contemporary

history and critical humanitarian issues. I do it because I love photography,

I think it is imperative that the world is informed and aware about

the condition of humanity on our planet and images are one of the best

ways of conveying this reality to a wider public. I hope that in a small

way my work and the collective work of all journalist will contribute

to better understanding and eventual resolution of the many conflicts

and injustices that exist in our societies. At times this entails considerable

personal and financial risks. Like all independent photographers, especially

in the current economic environment of the editorial world, it is extremely

difficult to make a decent living. However, I've been doing this long

enough and have a good enough relationship with my editors and the magazines

that I can usually make it pay. Noone pursues this profession to make

money though. On the other hand, the experiences that I have and the

people that I meet while doing this work are more valuable and add more

personal wealth to my life than any potential financial rewards could

ever provide. Perhaps I'm crazy, but I think it's worth it. I'd like

to thank Kodak France for generously providing the film for this project.

|