|

Videosmith

by Steven Trent Smith

The More

Things Change...

|

|

The

first international crisis to be covered electronically by the major

U.S. networks was the revolution in Iran in early 1979.

When the story broke, the news divisions overseas were still shooting

16mm film. It was possible to get the film processed in Tehran and uplinked

through the facilities of Iranian television. But when events turned

against the Shah, the film processor and the satellite link were conveniently

made “unavailable.” This forced the networks to charter Learjets

down to Amman, Jordan, to process, edit and feed unfettered. This was,

of course, very expensive, and slowed down dissemination of the news.

It also led to the death of an ABC producer when his charter crashed

due to pilot error.

As the story progressed, electronic coverage began to grow. In those

days, each network had its own “branding” for their video

acquisition. ABC used ENG (Electronic News Gathering). CBS used ECC

(Electronic Camera Coverage). And NBC used EJ (Electronic Journalism).

No matter what it was called, it revolutionized the way the nets covered

major stories.

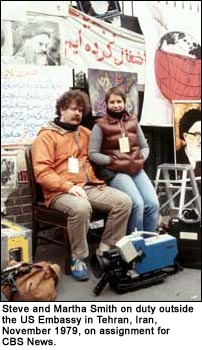

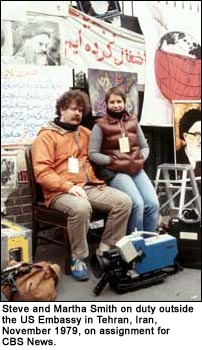

A

two-person crew (camera and sound) using a “portable, broadcast-quality

color camera,” (i.e., an RCA TK-76 or Ikegami HL-77, each of which

weighed 30 pounds or more) went out to shoot the story. These early

cameras were not very good by today’s standards. In fact, I think

a $3400 Canon XL-1 could run circles around the $34,000 A

two-person crew (camera and sound) using a “portable, broadcast-quality

color camera,” (i.e., an RCA TK-76 or Ikegami HL-77, each of which

weighed 30 pounds or more) went out to shoot the story. These early

cameras were not very good by today’s standards. In fact, I think

a $3400 Canon XL-1 could run circles around the $34,000

TK-76 Martha and I used. Of course we didn't have camcorders in those

days. The poor sound recordist had to lug around a 3/4" U-Matic

field recorder. The choices were few. Sony made the BVU-100, a hugely

overweight machine that even football-sized men had difficulty handling.

JVC made the CR-4400U– not as rugged, perhaps, but a good ten pounds

lighter (and something five foot Martha could wrestle around without

getting hurt).

When we had done our bit, our twenty-minute cassettes were taken back

to the “portable edit system.” This consisted of a pair of

Sony BVU-200 3/4" recorder/players, each weighing about a hundred

pounds, and a bulky BVE-500 edit controller. Add to that a pair of twelve-inch

monitors and other miscellany, and you’re ready to cut. The cost

of all this? About $35,000. There was no time code then; editors had

to go by “control track numbers” and tape counters. A “precision

edit” was anything within plus or minus two frames. The BVU’s

were pretty reliable machines. When you hit the “Edit” buttons

the controller would backspace both machines, lock them up, release

them and make the edit. The sound a proper edit made was most reassuring.

Big solenoids in the decks provided the noise. First there would be

a slight “clunk” (reversing the transport). Then there would

be a good, solid “kathunk!” (the solenoids kicking in). That

was followed by a another slight “clunk” and sometimes a tiny

“screech” (the transport stopping and the tape slipping).

Another solid “kathunk” indicated the switching of the solenoids

to forward. And finally, at the inexact edit point there would be a

barely audible “click.” Any deviation from this sequence indicated

a glitch that might or might not grind the editing process to a halt.

While the editor and producer were screening and logging the raw footage,

the correspondent was usually off writing a script. When he or she had

finished, a call was placed to a senior producer in New York, the script

was read over the phone, perhaps modified, then approved.

After the piece was cut, it would be taken off to Iranian television

to be fed back to the States (assuming they were cooperative that night).

The nets usually shared a BVU-200 and a Time Base Corrector (TBC, used

to stabilize the image to meet broadcast standards). One day the TBC

flaked out on us, just showing garbage on our monitor. Thinking we had

nothing to lose, I banged my fist twice on the top and once on the side.

That startled the TBC into working again. Satellite time was enormously

expensive - running into the thousands of dollars per hour. Sometimes

a little “baksheesh” traded hands to keep the “bird”

open and the censors off our backs. But we got the job done and were

pretty proud of ourselves.

We all thought, way back then, that this stuff looked beautiful and

wondered how it could ever be improved. Boy, were we naive.

Twenty-two years later “America’s New War” (branding

courtesy of CNN) has brought yet another revolution to video news coverage

in faraway places.

Much of what we are watching from Afghanistan now is shot with small

format cameras (ranging from single-chip miniDV to three-chip professional

DVCam and DVCPro). Much of what we are watching is edited on laptop

systems - either dedicated units or PC’s and Mac’s. And when

it comes time to feed this material, some of what we are watching is

sent via satellite telephone. One iteration of this is the “videophone”

popularized by CNN and now copied by all the rest. Due to bandwidth

limitations. The images are jerky and hard to watch, but the point is

we can now see live images from any place on this planet, and without

the interference of meddling, autocratic

governments. Given time, the images will only get better and better.

That’s progress - as long as television journalists are responsible

and accountable for the coverage they provide us.

But there is a downside to all this technological malarkey: we sometimes

get too much information. In the U.S. we have three basic 24/7 news

channels available, plus whatever the networks throw at us, plus the

flood of stuff on the Internet. Television was long ago likened to the

Tower of Babel. But compared to what we have access to today, television

of twenty, thirty years ago seems like just a whisper. I've come to

believe this: That just because we can do it, doesn't mean we

should do it.

Steven

Trent Smith

Contributing Writer

stscam@bellatlantic.com

|

A

two-person crew (camera and sound) using a “portable, broadcast-quality

color camera,” (i.e., an RCA TK-76 or Ikegami HL-77, each of which

weighed 30 pounds or more) went out to shoot the story. These early

cameras were not very good by today’s standards. In fact, I think

a $3400 Canon XL-1 could run circles around the $34,000

A

two-person crew (camera and sound) using a “portable, broadcast-quality

color camera,” (i.e., an RCA TK-76 or Ikegami HL-77, each of which

weighed 30 pounds or more) went out to shoot the story. These early

cameras were not very good by today’s standards. In fact, I think

a $3400 Canon XL-1 could run circles around the $34,000