"Mourners

in the Dominican Republic"

By

Ricky

Flores

The Journal News

In

an unusual move for my paper, the editors of The Journal News in Westchester,

New York, decided to follow the story of the crash of American Airlines

flight 587, and send a me and a reporter down to the Dominican Republic.

I was informed last Tuesday of the decision and spent the next two

days dancing with the U.S. Passport Services trying to get my passport

renewed. You go about doing that by making an appointment via telephone

for an expedited processing of your application which allows you the

privilege to stand online and wait for several hours. In the end,

you get a desultory agent who looks over your application with a tinge

of contempt. Heaven forbid if any part of your application or if your

picture is not up to snuff because you'll be right back end of that

phone line making another appointment to stand on line again. I wonder

if the U.S. Passport Service is run like this throughout the world.

In

an unusual move for my paper, the editors of The Journal News in Westchester,

New York, decided to follow the story of the crash of American Airlines

flight 587, and send a me and a reporter down to the Dominican Republic.

I was informed last Tuesday of the decision and spent the next two

days dancing with the U.S. Passport Services trying to get my passport

renewed. You go about doing that by making an appointment via telephone

for an expedited processing of your application which allows you the

privilege to stand online and wait for several hours. In the end,

you get a desultory agent who looks over your application with a tinge

of contempt. Heaven forbid if any part of your application or if your

picture is not up to snuff because you'll be right back end of that

phone line making another appointment to stand on line again. I wonder

if the U.S. Passport Service is run like this throughout the world.

The editors wanted us to fly to the Dominican Republic on the very

same flight that had crashed. It is a popular flight and is usually

booked solid. One of the stories we covered had to do with the amount

of luggage that Dominicans take with them when they travel. Many of

the suitcases we saw were about the size of a sub-compact car, stuffed

with clothing and gifts for family members. The goods that were being

taken down were either really expensive to get in the Dominican Republic

or hard to find. The country is essentially a poor country which has

suffered for years under either repressive or corrupt political control.

The impact of that legacy is easily seen everywhere you go as you

travel around Santo Domingo or around the surrounding towns. The country

is in a perpetual state of repair/disrepair. You see construction

projects being put up but you can't get any clear indication when

they are going to be finished. Some of the construction sites we saw

made no sense at all and whose only purpose seemed to be to allow

people to work. Other sites were so severely understaffed it was clear

that they were not going to be finished at all.

For several days we worked on various stories centered around life

in the Dominican Republic while waiting for the first body from AA

Flt. 587 to arrive at Las Americas Airport in Santo Domingo. It finally

arrived on Monday night. We arrived at the airport late and were scolded

by a security guard. We used the "we are foreign press,"

excuse and that we had only just found out about the arrival. They

didn't ask for ID's; I guess, since I had my cameras with me, that

was sufficient identification. They barely checked my equipment before

they allowed us to go through. We were led to the gate where all the

other press was waiting for the arrival of the flight, which was an

A300 Airbus, the same that crashed in New York.

They finally brought the body out through a side gate in a hearse

that also contained two relatives. We knew it was customary to view

the body at a home within 24 hours before someone is buried so we

found out who he was and his address and tracked the family to Yamasa,

a small town 57 kilometers north of Santo Domingo.

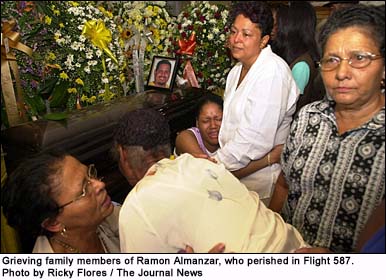

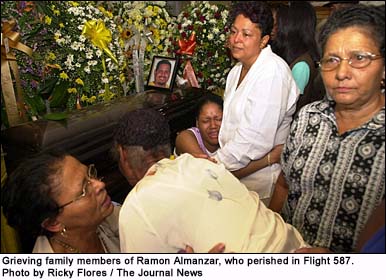

When

we arrived at Yamasa, what we saw was probably one of the most moving

sights in the entire trip. We were able to identify the house rather

quickly because over the street, in front of the house, was a tarp

which provided shade. The street was filled with people standing or

sitting in chairs that were provided for guests of the viewing. Immediately

inside of the tiny home was the closed casket of Ramon Omar Almanzar,

surrounded by flowers and grieving family members. You would think

that under these circumstances, the last thing that the family, relatives

or friends would want to see, would be a member of the press. They

turned out to be warm and welcoming and very giving. Part of the custom

in the Dominican Republic is to feed people who attend the viewing,

it can be anyone who happens to be there, no matter how remotely related

to the family they are. Volunteers came out with plates of food handing

them out to whoever was around the home. Several people, who clearly

were either homeless or desperately poor, were fed.

When

we arrived at Yamasa, what we saw was probably one of the most moving

sights in the entire trip. We were able to identify the house rather

quickly because over the street, in front of the house, was a tarp

which provided shade. The street was filled with people standing or

sitting in chairs that were provided for guests of the viewing. Immediately

inside of the tiny home was the closed casket of Ramon Omar Almanzar,

surrounded by flowers and grieving family members. You would think

that under these circumstances, the last thing that the family, relatives

or friends would want to see, would be a member of the press. They

turned out to be warm and welcoming and very giving. Part of the custom

in the Dominican Republic is to feed people who attend the viewing,

it can be anyone who happens to be there, no matter how remotely related

to the family they are. Volunteers came out with plates of food handing

them out to whoever was around the home. Several people, who clearly

were either homeless or desperately poor, were fed.

Shortly after the meal, they brought the body out and several hundred

people marched with it to the town church for a mass which was followed

by the burial at a small cemetery a few blocks away. The family was

devastated by the lost of Almanzar who apparently was a primary provider

for the entire family. He owned a small discotheque and the family

runs a small grocery store in town which employs some of the town

residents. He provided finances from other businesses he had and was

developing in New York. He left behind a wife and two children and

an entire community that cared for him.

I didn't know this man, never had the chance to speak with him or

find out what his life was like. But if there was any indication of

who he was, then what I saw in Yamasa was a testament to this one

man's life. Leaves you wondering about all the other lives that were

lost on Flight 587, a crash that many people felt actually relieve

in that it was created by mechanical failure as oppose to criminal

human design. How easy it was for many people to dismiss it afterward

as the details became clearer.

We left Yamasa knowing a little more about Mr. Almanzar. This was

not an insignificant life. The end of this life could not be neatly

put way or rationalized.

I guess my job as a photojournalist is to provide you with an example

of how a tragedy may affect those involved by focusing on a single

individual. But that poorly reflects the scope of the tragedy and

all the lives that are affected as a result. We can say the same about

Sept 11th. We focused on the Firefighters, Police and EMS workers

whose lost their lives that day, none of whom led insignificant lives,

but what about all the others? Those like Almanzar, who lost their

lives that day? Who did they leave behind?

Ricky

Flores

The Journal News

rigglord@msn.com

Ricky

Flores has been working as staff photographer for The Journal News,

a daily paper based in Westchester, N.Y for the pasted 8 years. Prior

to that he was a founding member of Impact Visuals and a freelance

photographer for The Village Voice and The New York Times.

In

an unusual move for my paper, the editors of The Journal News in Westchester,

New York, decided to follow the story of the crash of American Airlines

flight 587, and send a me and a reporter down to the Dominican Republic.

I was informed last Tuesday of the decision and spent the next two

days dancing with the U.S. Passport Services trying to get my passport

renewed. You go about doing that by making an appointment via telephone

for an expedited processing of your application which allows you the

privilege to stand online and wait for several hours. In the end,

you get a desultory agent who looks over your application with a tinge

of contempt. Heaven forbid if any part of your application or if your

picture is not up to snuff because you'll be right back end of that

phone line making another appointment to stand on line again. I wonder

if the U.S. Passport Service is run like this throughout the world.

In

an unusual move for my paper, the editors of The Journal News in Westchester,

New York, decided to follow the story of the crash of American Airlines

flight 587, and send a me and a reporter down to the Dominican Republic.

I was informed last Tuesday of the decision and spent the next two

days dancing with the U.S. Passport Services trying to get my passport

renewed. You go about doing that by making an appointment via telephone

for an expedited processing of your application which allows you the

privilege to stand online and wait for several hours. In the end,

you get a desultory agent who looks over your application with a tinge

of contempt. Heaven forbid if any part of your application or if your

picture is not up to snuff because you'll be right back end of that

phone line making another appointment to stand on line again. I wonder

if the U.S. Passport Service is run like this throughout the world. When

we arrived at Yamasa, what we saw was probably one of the most moving

sights in the entire trip. We were able to identify the house rather

quickly because over the street, in front of the house, was a tarp

which provided shade. The street was filled with people standing or

sitting in chairs that were provided for guests of the viewing. Immediately

inside of the tiny home was the closed casket of Ramon Omar Almanzar,

surrounded by flowers and grieving family members. You would think

that under these circumstances, the last thing that the family, relatives

or friends would want to see, would be a member of the press. They

turned out to be warm and welcoming and very giving. Part of the custom

in the Dominican Republic is to feed people who attend the viewing,

it can be anyone who happens to be there, no matter how remotely related

to the family they are. Volunteers came out with plates of food handing

them out to whoever was around the home. Several people, who clearly

were either homeless or desperately poor, were fed.

When

we arrived at Yamasa, what we saw was probably one of the most moving

sights in the entire trip. We were able to identify the house rather

quickly because over the street, in front of the house, was a tarp

which provided shade. The street was filled with people standing or

sitting in chairs that were provided for guests of the viewing. Immediately

inside of the tiny home was the closed casket of Ramon Omar Almanzar,

surrounded by flowers and grieving family members. You would think

that under these circumstances, the last thing that the family, relatives

or friends would want to see, would be a member of the press. They

turned out to be warm and welcoming and very giving. Part of the custom

in the Dominican Republic is to feed people who attend the viewing,

it can be anyone who happens to be there, no matter how remotely related

to the family they are. Volunteers came out with plates of food handing

them out to whoever was around the home. Several people, who clearly

were either homeless or desperately poor, were fed.