|

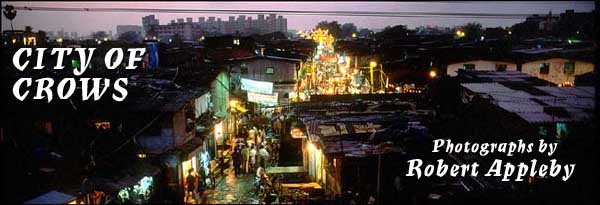

Introduction

by Robert Appleby

“Three things you’ll find even in heaven:

taxidrivers, paanwalas and hutments”

- Bombay taxidriver

The Bombay slums

are a byword for crime, squalor, dirty politics and communal riots,

and Dharavi, the much-vaunted “largest slum in Asia”, is the

biggest and most feared of the lot. Scene of some of the worst excesses

of the post-Babri Masjid riots of 92/93 in which an unknown number of

people lost their lives and entire districts were burnt to the ground

with the collusion of the city’s leading politicians, its reputation

for random violence and extreme poverty is still strong in the minds

of Bombay’s middle classes and the media, Indian and international

alike.

Drive downtown past Mahim Creek on the western express highway and you’ll

see the distant hutments huddled on the edge of the mangrove swamp dividing

North and South Bombay. The smell of the swamp is overpowering and the

beggars at the stoplights thrust their hands in through the windows

of your car, many of them sporting some extraordinary mutilation or

deformity. The giant water pipes running over the Creek are busy with

people walking on top of them to work in Bandra. Huge hoardings advertise

Bollywood movies, internet services and sometimes just the enormous

red number of the hoarding company itself. The noise and pollution are

intimidating and the slum in the distance seems like a gigantic anthill,

disgorging its insect-like denizens every morning and calling them back

in the evening. A threat to civilised city life. Certainly nowhere for

an outsider to venture.

Well, not really. Things move on, and Dharavi’s reputation no longer

reflects its reality. If Bombay has a heart, it must be this settlement

of nearly a million people dating back to the nineteenth century (the

oldest house dates back to 1840, and the cross at Koliwada is dated

1853), made up of immigrants to Bombay from all over India, many of

them still pursuing their traditional livelihoods in the context of

the country’s most cosmopolitan city.

When

downtown office workers break for a snack, they are likely to eat idlis

(fermented rice cakes) or sweets made here for consumption on the pavement

outside the Bombay Stock Exchange. Leather goods, traditional pottery

items, clothes - a vast range of goods are made in Dharavi for sale

in India and abroad. And though the stigma of living here still attaches

to them, many young residents are studying computer science and business

administration and opening businesses here and elsewhere. Far from being

an economic refugee camp, as it is so often portrayed, Dharavi is a

vibrant, energetic business and manufacturing district for many of its

residents. When

downtown office workers break for a snack, they are likely to eat idlis

(fermented rice cakes) or sweets made here for consumption on the pavement

outside the Bombay Stock Exchange. Leather goods, traditional pottery

items, clothes - a vast range of goods are made in Dharavi for sale

in India and abroad. And though the stigma of living here still attaches

to them, many young residents are studying computer science and business

administration and opening businesses here and elsewhere. Far from being

an economic refugee camp, as it is so often portrayed, Dharavi is a

vibrant, energetic business and manufacturing district for many of its

residents.

There are problems, of course, the typical insecurities of the slums:

the threat of having your house demolished by the authorities, unavailability

of capital for new businesses, the constantly changing legislation which

threatens livelihoods and homes, the grinding bureaucracy in the way

of every new venture, lack of infrastructure and overcrowding - these

are some of the complaints most often voiced by residents.

The

heart of the matter is housing. While official real estate prices are

among the highest in Asia, Bombay has made no provision for the unceasing

influx of people from small towns and villages all over India. Half

of the city’s people (an unknown number, but certainly in the five

to seven million range) live in its nearly 2000 slums, and their place

of residence is often no indicator of their economic status, although

the better-off will generally prefer to find proper housing elsewhere.

The fact is that often better housing is simply not available at prices

that even the well-off can afford. On the other hand, slum residents

have no guarantees or security, anddo not own their homes. The

heart of the matter is housing. While official real estate prices are

among the highest in Asia, Bombay has made no provision for the unceasing

influx of people from small towns and villages all over India. Half

of the city’s people (an unknown number, but certainly in the five

to seven million range) live in its nearly 2000 slums, and their place

of residence is often no indicator of their economic status, although

the better-off will generally prefer to find proper housing elsewhere.

The fact is that often better housing is simply not available at prices

that even the well-off can afford. On the other hand, slum residents

have no guarantees or security, anddo not own their homes.

As a woman living on the edge of the Central Railway said to me while

I was photographing her washing her family’s clothes just a couple

of metres away from the passing commuter trains: “If we could ask

for one thing, it would be better sanitation. And to keep our homes”.

When I revisited the area nine months later, those houses were being

demolished, although recent changes in offical attitudes have led to

legislation ensuring that residents are relocated to new housing within

the city rather than, as happened in one notorious case in the early

‘80s, being driven in their thousands to the city limits and told

to walk “home” - back to the villages from which their parents

and grandparents came to Bombay. This obligation on the part of the

authorities means that wholesale slum clearances are now probably a

thing of the past, even though the residents are still not registered

owners of their homes or land. Although it might seem evident that formal

ownership of property is the key to economic growth, such perceptions,

and the policies that might grow out of them, are far in Bombay’s

future.

Kumbharwada,

the pottery colony off 90 Feet Road, is emblematic of the pressures

on livelihoods in Dharavi. When the Kumbhars, a community of potters

from Gujarat, were first relocated here from elsewhere in Bombay in

1933 (after two previous relocations, always to the northern edge of

the city as it was defined at the time), they found a swampy, uninhabited

district with plenty of space for their kilns and houses. Now 1200 families

live in an area of 22 acres. A visitor’s first impression may well

be that Kumbharwada is less crowded than the rest of the slum, since

the houses are separated by wide lanes. But all free space is taken

up by kilns for firing the traditional earthenware pottery that the

community makes for the domestic market and Indian communities worldwide.

There is no room for expansion. The potters themselves are well aware

of the need to address these problems; for instance, they know that

to be competitive in the long term, they must fire modern ceramics rather

than earthenware. But such projects are unrealisable without the infrastructure

or space for new kilns, combined with the limited means available to

people who have no collateral and must look for investment capital within

their restricted family groups. In the meantime many young people are

turning to new occupations, such as carpentry, diamond cutting and the

merchant navy, and plastic is replacing earthenware as a material for

many of the articles produced here. Kumbharwada,

the pottery colony off 90 Feet Road, is emblematic of the pressures

on livelihoods in Dharavi. When the Kumbhars, a community of potters

from Gujarat, were first relocated here from elsewhere in Bombay in

1933 (after two previous relocations, always to the northern edge of

the city as it was defined at the time), they found a swampy, uninhabited

district with plenty of space for their kilns and houses. Now 1200 families

live in an area of 22 acres. A visitor’s first impression may well

be that Kumbharwada is less crowded than the rest of the slum, since

the houses are separated by wide lanes. But all free space is taken

up by kilns for firing the traditional earthenware pottery that the

community makes for the domestic market and Indian communities worldwide.

There is no room for expansion. The potters themselves are well aware

of the need to address these problems; for instance, they know that

to be competitive in the long term, they must fire modern ceramics rather

than earthenware. But such projects are unrealisable without the infrastructure

or space for new kilns, combined with the limited means available to

people who have no collateral and must look for investment capital within

their restricted family groups. In the meantime many young people are

turning to new occupations, such as carpentry, diamond cutting and the

merchant navy, and plastic is replacing earthenware as a material for

many of the articles produced here.

The

city is the natural stage for such collisions between traditional community

livelihoods and the new urban reality. Significantly, communities which

have adapted and diversified, like the Kumbhars or the Kolis, the original

fisherpeople of the Bombay islands, have prospered while those which

have clung to single trades have tended to stagnate. Very few Kolis

now make their living fishing: the Creek, where they once practised

their unique style of net fishing, has silted up and the few remaining

fishermen now breed the fish they catch in large ponds in the interior

of the mangrove swamp. The majority of them now work in other jobs around

Bombay, as diverse as hotel management and the merchant navy, and their

community identity is no longer rooted in a particular livelihood. On

the other hand, the metalworker’s settlement near the water pipes

has failed to prosper, while most residents continue to pursue their

traditional trade. The

city is the natural stage for such collisions between traditional community

livelihoods and the new urban reality. Significantly, communities which

have adapted and diversified, like the Kumbhars or the Kolis, the original

fisherpeople of the Bombay islands, have prospered while those which

have clung to single trades have tended to stagnate. Very few Kolis

now make their living fishing: the Creek, where they once practised

their unique style of net fishing, has silted up and the few remaining

fishermen now breed the fish they catch in large ponds in the interior

of the mangrove swamp. The majority of them now work in other jobs around

Bombay, as diverse as hotel management and the merchant navy, and their

community identity is no longer rooted in a particular livelihood. On

the other hand, the metalworker’s settlement near the water pipes

has failed to prosper, while most residents continue to pursue their

traditional trade.

But division of work along community lines is still a central feature

of life here. This is strikingly evident in the case of plastics recycling,

for instance, where each stage in the process is handled by a different

community, often from very different parts of India. The bags are first

collected by scavengers, often gardulas (brown sugar smokers), and sold

to muslim merchants who then deliver the bags for washing to a lane

of tamilians off 60 Feet Road. Their task is to wash and dry the bags,

after which they are again packed off to another part of the slum for

further treatment.

With its many industries, Dharavi also has its darker side. Many jobs

are dangerous and badly paid, such as cotton carding or brass buckle

manufacture. Protection rackets and official corruption are rife when

people have no legal right to live or run their businesses where they

do. And despite the availability of schools in the slum itself, many

children are obliged to work, often at stunting, unhealthy jobs.

The

central event in the recent history of Bombay, the 1993 riots, has also

left its mark on Dharavi. Chamra Bazar, the muslim tannery district,

was largely razed to the ground. People speak of seeing entire rows

of houses destroyed with only single buildings - those belonging to

the “correct” community - left standing. Indeed, many of the

hutments date from the rebuilding in the aftermath of the riots. But

despite the events of the time, the ten years since the riots have proved

beneficial for Dharavi in many ways. In particular, the police presence

in the slum has increased, with small stations on many streets, and

this has largely driven out the more blatant forms of organised crime,

and enabled a middle class to emerge in what was previously a notoriously

mafia-dominated area. New legislation has enabled residents’ associations

to engage building contractors to redevelop their dwellings into multi-storey

apartment blocks, and it is tempting to see such initiatives as a tacit

recognition by the authorities that the solution to the “problem”

of Dharavi is to give the people themselves the tools to improve their

condition. Dharavi itself is fast becoming a desirable residential area,

with its new buildings near to the Western and Central Railways conveniently

located for commuters to other parts of Bombay. The

central event in the recent history of Bombay, the 1993 riots, has also

left its mark on Dharavi. Chamra Bazar, the muslim tannery district,

was largely razed to the ground. People speak of seeing entire rows

of houses destroyed with only single buildings - those belonging to

the “correct” community - left standing. Indeed, many of the

hutments date from the rebuilding in the aftermath of the riots. But

despite the events of the time, the ten years since the riots have proved

beneficial for Dharavi in many ways. In particular, the police presence

in the slum has increased, with small stations on many streets, and

this has largely driven out the more blatant forms of organised crime,

and enabled a middle class to emerge in what was previously a notoriously

mafia-dominated area. New legislation has enabled residents’ associations

to engage building contractors to redevelop their dwellings into multi-storey

apartment blocks, and it is tempting to see such initiatives as a tacit

recognition by the authorities that the solution to the “problem”

of Dharavi is to give the people themselves the tools to improve their

condition. Dharavi itself is fast becoming a desirable residential area,

with its new buildings near to the Western and Central Railways conveniently

located for commuters to other parts of Bombay.

The word “slum” conjures up a degraded settlement of the impoverished,

of those who have failed the test of modern city life. But my visits

to Dharavi impressed upon me the boundless energy and ingenuity of its

people, and their ability to in-corporate traditional values into the

changes forced on them by the pressures of life in Bombay. The challenges

and obstacles are overcome every day, often in unexpected ways. The

cross at Koliwada, for instance, bears the date 1853, and is often cited

as a testament to the age of the community. But as Jacob Patil, the

gaonpatil or mayor of Koliwada, told me, the cross itself was erected

in 1960. “I put that cross up in 1960, but I knew that a new cross

would be knocked down by the police when they came to know of it. So

I put the date 1853 on it, and pretended it had always been there, unnoticed.

Now it’s in the history books!”

|

![]()