|

Passing

the Baton in Vietnam

by Horst Faas

The Vietnam experience

had formed a whole generation of photojournalists. Those who covered

the war from Saigon and are still alive are ending their careers in

the fading glow of what was often the high point of their journalistic

life. Many have already retired. The photographer-soldiers on the Communist

side have finally come out of the shadows. Their dead have been honored

with exhibitions and books and those who survived can finally tell their

tale.

Some of the best of a new generation of Vietnamese photo journalist

and some very eager want-to-be photographers gathered in Ho Chi Minh

City earlier this year for a rare opportunity to meet and learn from

western photojournalists with extensive past and current experiences.

The old Vietnam War was barely mentioned. The state of the art of today's

photojournalism was the topic.

The

first international workshop on photojournalism was organized by the

Indochina Media Memorial Foundation (IMMF) in cooperation with the Vietnam

Association of Photographic Artists (VPA) and the Vietnam News Agency

(VNA). The

first international workshop on photojournalism was organized by the

Indochina Media Memorial Foundation (IMMF) in cooperation with the Vietnam

Association of Photographic Artists (VPA) and the Vietnam News Agency

(VNA).

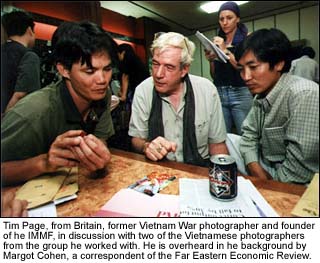

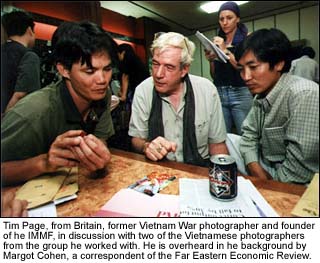

The IMMF was conceived in 1991 by British photographer and author Tim

Page. He wanted to do something to mark the lives and deaths of almost

200 media colleagues, from many countries, killed or missing while covering

all sides of the wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos over thirty years,

from 1945-1975.

The conflict in Indochina more than any other, before or since, highlighted

the role of the media in war. For the journalists involved in the IMMF,

the memory of lost colleagues has provoked a desire to support the development

of good practice in journalism in the region where this piece of history

unfolded, as well as a desire to put something back into the country

where their professional careers were made.

The young Vietnamese photographers and their tutors - including two

old timers who had been there during the war - were based at the Rex

Hotel, conveniently in the center of Ho Chi Minh City which is marked

by a large statue of Ho Chi Minh in front of the adjacent City Hall.

The Rex was the headquarters of the U.S. military's information services,

when this city was known as Saigon and the daily military briefings

were called the "Follies."

Twenty-eight

Vietnamese photographers took part - of average age of 30 and seven

women among them - representing print media from across Vietnam, including

the Saigon Times, the Vietnam Economic Times, the Vietnam Investment

Review, Ho Chi Minh City Women's Magazine, the Vietnam News Agency and

an array of local newspapers. There were also four freelancers, a rare

breed in Vietnam. Already in the pre-selection of candidates for the

workshop Vietnamese officials objected to freelancers who the IMMF had

nominated and four had to be withdrawn and were subsequently replaced

by staff from government controlled papers. "They are too free,"

one Vietnamese official commented. Of the 28, nine came from Hanoi,

fifteen from Ho Chi Minh City and four from elsewhere in Vietnam, towns

such as Hue and Dalat. Twenty-eight

Vietnamese photographers took part - of average age of 30 and seven

women among them - representing print media from across Vietnam, including

the Saigon Times, the Vietnam Economic Times, the Vietnam Investment

Review, Ho Chi Minh City Women's Magazine, the Vietnam News Agency and

an array of local newspapers. There were also four freelancers, a rare

breed in Vietnam. Already in the pre-selection of candidates for the

workshop Vietnamese officials objected to freelancers who the IMMF had

nominated and four had to be withdrawn and were subsequently replaced

by staff from government controlled papers. "They are too free,"

one Vietnamese official commented. Of the 28, nine came from Hanoi,

fifteen from Ho Chi Minh City and four from elsewhere in Vietnam, towns

such as Hue and Dalat.

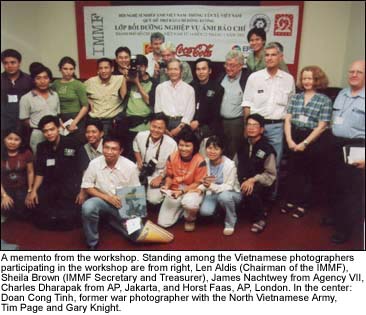

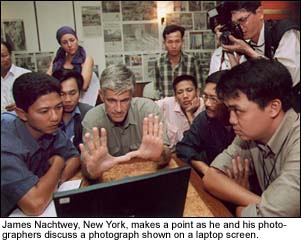

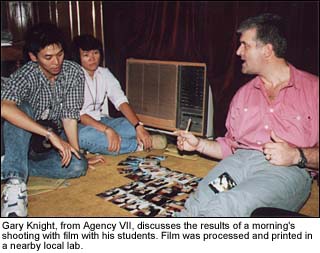

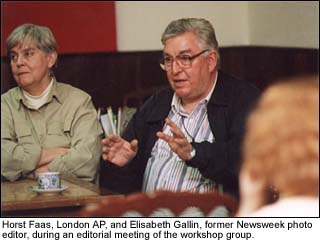

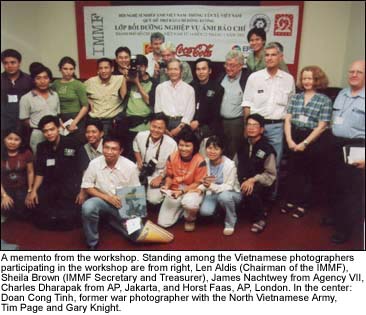

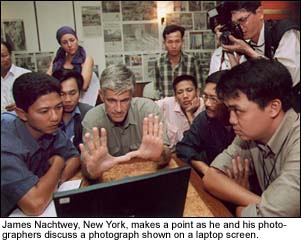

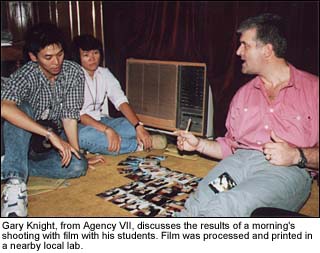

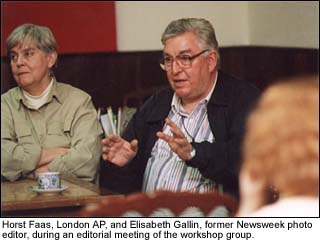

The tutors were James Nachtwey, an American, who after a career with

Magnum now works with Agency VII; Gary Knight, a Briton, also with Agency

VII; Elisabeth Gallin, a retired picture editor for Newsweek; Tim Page,

a British freelancer out of Kent, England, Charles Dharapak, an American

with The Associated Press based in Jakarta; and Horst Faas, a German,

now senior European photo editor with AP in London.

Tim Page and Horst Faas were working in Vietnam during the war, Page

from 1965 to 1969, Faas from 1962 to 1974. James Nachtwey, now 54, told

the Vietnamese during one of his presentations that the photos he saw

of the Vietnam war as a teenager, especially Nick Ut's picture of the

napalm scarred child running down a road in 1972 inspired him to become

the news photographer he is today, having covered wars and human misery

for the past twenty years.

The

Vietnamese were divided into five groups, each of which worked with

the same tutor throughout the eight-day session. They went out on the

streets every day, learning to experiment with photo angles, choose

the right lens and, most important, find the telling image. They also

were urged to challenge the worry of offending officials, while recognizing

that is a legitimate concern in this one-party communist nation. The

Vietnamese were divided into five groups, each of which worked with

the same tutor throughout the eight-day session. They went out on the

streets every day, learning to experiment with photo angles, choose

the right lens and, most important, find the telling image. They also

were urged to challenge the worry of offending officials, while recognizing

that is a legitimate concern in this one-party communist nation.

"There have always been authorities who were afraid of the picture,"

Faas commented during a session in which the students were shown noted

samples from the history of photo journalism. He told his audience that

one of the few issues the post-World War II occupying forces in his

hometown of Berlin could agree on was that ordinary people shouldn't

be allowed to wield a camera.

Originally the workshop's project was to cover news and current events

in Ho Chi Minh City and work on a number of relevant photo essays. However,

despite a score of newspapers, a myriad of magazines and Vietnam News

Agency reports available on the Internet it proved impossible to set

up a diary of upcoming events. All news seem to be a state secret -

and despite being part of the workshop Vietnam News Agency would not

reveal their daily events list of such pedestrian events as soccer matches,

inaugurations, press conferences.

Vietnam remains a country where it is possible to find out everything

happening in the outside world through the Internet or international

television broadcasts, but little of he news around you. Nothing will

happen as a news event or will be noted in print and picture unless

authorities have consented that people in Vietnam should know. The lack

of unrestricted and free information is a stark reminder that Vietnam

is still one of the few countries ruled by the Communist party.

"The only way to get into print here is to have as many party members

in the picture as possible," one Vietnamese photographer commented.

Thus handicapped, the workshop project, to which everybody contributed,

set off to record *Eight Days in Ho Chi Minh City* under the managing

editorship of Elizabeth Gallin. By the end of the eight days there was

to be an exhibition of 49 of the best pictures taken during the workshop,

and a 82-page digital picture magazine.

Vietnamese photographers still rely primarily on film and prints, with

very few using low-grade digital cameras. Only one of the 28 photographers

had his own laptop. For most Internet cafes are the points of access

to the Internet.

Supplied by Canon, Epson and The Associated Press, nine digital cameras,

desktops and six laptops gave the Vietnamese their first ever chance

to experience digital photography, and all of them loved it. The photography

of many showed marked improvements. Many had also never used long or

zoom lenses - professional tools still a luxury and beyond the financial

reach of most photographers and publications in Vietnam.

At the end some 14,500 images were exposed on Kodak 400 film, as well

as some ten thousand digital images stored.

Evening presentations by he tutors confronted the Vietnamese with famous

news photographs which many had never seen - only few photo books are

available in Vietnam, although pirated novels and books about Vietnam

and the war are available at every corner in downtown HCMC.

James Nachtwey drew a full house when he showed his portfolio of twenty

years covering hellish places.

Charles Dharapak held several primer sessions on the use of digital

equipment and Photoshop.

Horst Faas presented the Vietnamese one day with a tour de force show

of the history of photojournalism and the use of photography in magazines.

On another day he showed a rapid sequence of news photographs from the

past hundred years that have become well remembered historical icons

in the west, but were for the most part new to the fascinated Vietnamese.

Gary

Knight explained how web sites and the Internet can be used as tools

of today's photojournalism. Gary

Knight explained how web sites and the Internet can be used as tools

of today's photojournalism.

Tim Page, who has spent much time in recent years discovering and exploring

photography of the "other side," the communist side of Vietnam,

introduced Doan Cong Tinh who, born in 1943, is one of the few soldier-photographer

survivors of the Vietnam war. Both showed the work and spoke of the

experiences of the now old war photographers. But some in the young

audience were skeptical."I know very well, how many of their pictures

had to be posed as ordered by the commissars," one said.

This was the only time the war became a topic of discussion. Before

the tutors first met with their young Vietnamese colleagues it was decided

not to mention the war and our own war experiences - and the Vietnamese

never asked. Born during the end-years of the war or thereafter, questions

raised by the young photographers in forum discussions and in the many

personal chats concerned mainly how to improve in the profession today

and achieve a better life tomorrow.

A planned discussion about the problems and future of photo journalism

that was to involve all photographers and tutors came to an abrupt end

with a patronizing speech by one of the HCMC government news agency

officials.

"Do not forget that we expect you to come out of this workshop

according to our expectations. You must emerge as a better photographer

for your country. Your photography will improve if it serves your country,

it will be bad if it does not serve your country.

Some of you will come out of this workshop having enhanced your reputation

with us - some will not. Talk amongst yourself and decide what you should

be taking pictures of and of what you should not. You need not always

talk to your tutor," he admonished the photographers. Nobody had

anything to say anymore and the session ended.

The

Vietnamese were more comfortable sitting with their tutor in small groups

around a computer or a stack on contact prints. Their interpreters,

too, were more relaxed and more forthcoming when they could not be The

Vietnamese were more comfortable sitting with their tutor in small groups

around a computer or a stack on contact prints. Their interpreters,

too, were more relaxed and more forthcoming when they could not be

overheard by outsiders hanging about.

Many made. ample notes of what their tutors said. "Think with your

head. Take (pictures) with your heart. Always follow your subject."

Photographer Bui Buu Ha had noted down from James Nachtwey's remarks

explaining how he works. Bui had the difficult assignment to produce

an essay on the care for children with mental disabilities.

The workshop was called a boot camp with drills in the basics: The technical

challenges were often overwhelming with the digital cameras and long

zoom lenses most photographers had never experienced. For their newspapers

most photographers usually just photograph head-on, with no special

angles, no attempts to see a picture in a new, different way. The editors

don't want it any other way.

During the workshop they were asked to compose fascinating frames, approach

their subject from different angles, make use of dramatic available

light and to penetrate into the minds or meaning of their subjects.

The tutors learned quickly what their students had experienced throughout

their careers: The big hindrances to developing an individual photographic

style is the worry of offending the sensibilities of the ruling establishment.

Even a routine assignment requires a bundle of official permission papers.

Taking pictures of about anything sensitive even in the streets, is

forbidden or instantly challenged by the omnipresent eyes and ears of

the government. Once the members of "Inter-Ministerial Inspection

team 844TP" started to look through the photographs taken during

the workshop assignments such as a look of the increasing prostitution

in HCMC, the trade with young prostitutes between Cambodia and Vietnam

and the Vietnam government's measures to stop it had to be dropped at

the strong recommendation of these observers.

The Vietnamese photographers did not argue with the representatives

of the political establishment. They did not complain. But they diligently

worked around the groundrules and stay out of politics, with astonishing

results.

"It was a great reward for me to see how within a few days often

sullen photographers who had initially produced dull and unimaginative

pictures picked up our ideas and suggestions and came back with attractive

or meaningful images," said Horst Faas.

"During the war some of the best and most aggressive and at the

same time sensitive photographers were Vietnamese," Horst reminisced,

adding"Now I spotted many talents amongst our young colleagues

with whom I would love to work with now."

James Nachtwey commented after the workshop: "We lit a fire there,

and the cast of characters was all-time."

The last day and what was to be the closing ceremony of the workshop

ended in confusion, with the distinct absurdity of a Franz Kafka novel.

The plan was to exhibit fifty of the workshop photographers best pictures,

discuss the 84-page magazine layout that had been produced as a computer

generated layout (without texts and captions) and then present awards,

mostly books on photography.

The "Inter-ministerial Inspection Team" had already vetoed

several photos: that of a beggar, a picture of an old man in a houseboat

and a few others for reasons only known to themselves. They were withdrawn.

For several days the chairman of the IMMF, Len Aldis, had patiently

negotiated with them - until it emerged that the IMF's co-organizers

of the workshop, the Vietnam Association of Artistic Photographers in

Vietnam and Vietnam News Agency had failed to obtain an exhibition

permit from the Ministry of Culture.

The remaining 47 pictures were on the walls, the buffet had been set

up as well as the still corked wine bottles. An obligatory ribbon held

the gathering crowd in the corridor. Still no word from the ministry.

Then a surprising little ceremony with speeches in a side room during

which Tim Page and Horst Faas were awarded medals bestowed by the Photographers

Association for their work in connection with the Requiem exhibition

project. Some of the students got up to present gifts to their tutors,

and Nguyen Hoai Linh, the senior and one of the most talented among

the photographers gave a moving "thank you" speech. With a

twinkle in his eyes, directed at the tutors, he ended, "Let us

not forget that it was the great Lenin who said "Truth is the Power

of Journalism."

He later assured his tutor that Lenin indeed wrote that. The name Lenin

triggered roaring applause from officials, photographers and all - and

at least some wine bottles were uncorked. But the exhibition remained

officially closed. While the speeches ended the document from the Ministry

of Culture had arrived.

It said, "The exhibition of photographs at Rex Hotel does not have

a license from responsible authorities and has not passed the required

inspection stage by the responsible authorities. After hearing the report

from the organizers of the exhibition, the Inter Ministerial Inspection

team 844TP decided to suspend the exhibition. Etc."

Once this was public, the officials left and the Vietnamese photographers

took their pictures from the wall and lined them up on the floor, leaning

against the wall. One photographer took control of the computer and

projected the workshop magazine. Another wrote a sign "Private

Party" and hung it in the corridor. The tutors watched in amazement

from the door as the students took over the floor.

When the trays and bottles were empty many retired to a nearby bar and

it became a long night. Many exchanged their E-mail addressees with

the tutors, who have been busy since answering E-mail's with questions

asking for counsel and advice.

One photographer took it a step further. Translating AP's Brian Horton's

book 'Introduction to Photojournalism' he found a quote from Bob Lynn,

a newspaper graphic consultant who said: "A young person should

just shoot from the heart and the gut and shoot the pictures that he

likes. If you are at a paper that doesn't appreciate it, then you have

to move to a paper that does appreciate it."

The photographer added (the name is withheld to protect him): "The

local newspaper I'm working for really doesn't appreciate what I tried

to practice what has been taught at the IMMF workshop. I intend to quit

my job and go freelance or work for other media agencies. " His

tutor wishes him well.

View

a Selection of Nine Photographs from

the Vietnam Photojournalism Workshop.

|

The

first international workshop on photojournalism was organized by the

Indochina Media Memorial Foundation (IMMF) in cooperation with the Vietnam

Association of Photographic Artists (VPA) and the Vietnam News Agency

(VNA).

The

first international workshop on photojournalism was organized by the

Indochina Media Memorial Foundation (IMMF) in cooperation with the Vietnam

Association of Photographic Artists (VPA) and the Vietnam News Agency

(VNA). Twenty-eight

Vietnamese photographers took part - of average age of 30 and seven

women among them - representing print media from across Vietnam, including

the Saigon Times, the Vietnam Economic Times, the Vietnam Investment

Review, Ho Chi Minh City Women's Magazine, the Vietnam News Agency and

an array of local newspapers. There were also four freelancers, a rare

breed in Vietnam. Already in the pre-selection of candidates for the

workshop Vietnamese officials objected to freelancers who the IMMF had

nominated and four had to be withdrawn and were subsequently replaced

by staff from government controlled papers. "They are too free,"

one Vietnamese official commented. Of the 28, nine came from Hanoi,

fifteen from Ho Chi Minh City and four from elsewhere in Vietnam, towns

such as Hue and Dalat.

Twenty-eight

Vietnamese photographers took part - of average age of 30 and seven

women among them - representing print media from across Vietnam, including

the Saigon Times, the Vietnam Economic Times, the Vietnam Investment

Review, Ho Chi Minh City Women's Magazine, the Vietnam News Agency and

an array of local newspapers. There were also four freelancers, a rare

breed in Vietnam. Already in the pre-selection of candidates for the

workshop Vietnamese officials objected to freelancers who the IMMF had

nominated and four had to be withdrawn and were subsequently replaced

by staff from government controlled papers. "They are too free,"

one Vietnamese official commented. Of the 28, nine came from Hanoi,

fifteen from Ho Chi Minh City and four from elsewhere in Vietnam, towns

such as Hue and Dalat. The

Vietnamese were divided into five groups, each of which worked with

the same tutor throughout the eight-day session. They went out on the

streets every day, learning to experiment with photo angles, choose

the right lens and, most important, find the telling image. They also

were urged to challenge the worry of offending officials, while recognizing

that is a legitimate concern in this one-party communist nation.

The

Vietnamese were divided into five groups, each of which worked with

the same tutor throughout the eight-day session. They went out on the

streets every day, learning to experiment with photo angles, choose

the right lens and, most important, find the telling image. They also

were urged to challenge the worry of offending officials, while recognizing

that is a legitimate concern in this one-party communist nation. Gary

Knight explained how web sites and the Internet can be used as tools

of today's photojournalism.

Gary

Knight explained how web sites and the Internet can be used as tools

of today's photojournalism. The

Vietnamese were more comfortable sitting with their tutor in small groups

around a computer or a stack on contact prints. Their interpreters,

too, were more relaxed and more forthcoming when they could not be

The

Vietnamese were more comfortable sitting with their tutor in small groups

around a computer or a stack on contact prints. Their interpreters,

too, were more relaxed and more forthcoming when they could not be