Mountain

Light

and Sporting Life

By Peter Howe

|

|

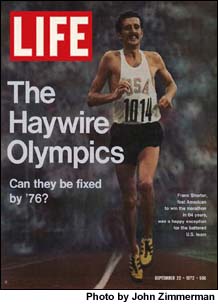

The photographic

firmament is much darker than the last time I wrote this column. Two

of its brightest stars are missing, both dying within eight days of

each other in early August. One was the groundbreaking sports photographer

John G. Zimmerman who died of lymphoma in Monterey California. The other

was the poetic visionary of nature photography, Galen Rowell, who tragically

perished with his wife Barbara in the crash of a light aircraft returning

to their home in Bishop, also in California. I worked with both of them

during my time as a picture editor, on many occasions with Galen, but

only once with John.

The

word "pioneer" is one of those words like "hero"

that is used so loosely as to devalue its meaning, but if it was ever

an appropriate description of a photographer it would be to describe

John Zimmerman. Nowadays we are so used to seeing the techniques that

he invented and perfected that we forget that forty years ago they were

revolutionary. He was the first to use remote cameras placed in unlikely

places such as ice hockey nets, or on the backboards of basketball hoops;

nobody had used blur to express rather than capture the motion of sports;

he used multiple strobe techniques to reveal the grace and complexity

of athletic movement as he did in a masterful way in a 1980 sequence

showing US Olympic diver Jenny Chandler arc through the air, enter the

pool and swim towards the camera underwater. His techniques have often

been imitated since he created them, but they have rarely been equaled,

because to John these were not merely technological tricks, but a way

of involving the reader in the action to a degree that still photography

had been unable to achieve before him. With John at a hockey match you

weren't by the ice but on it; the best seats in a Nicks game didn't

get you as close to those swirling giants as his spreads in Sports Illustrated.

With Zimmerman behind the lens you weren't just a fan, you were a fan

with access. The

word "pioneer" is one of those words like "hero"

that is used so loosely as to devalue its meaning, but if it was ever

an appropriate description of a photographer it would be to describe

John Zimmerman. Nowadays we are so used to seeing the techniques that

he invented and perfected that we forget that forty years ago they were

revolutionary. He was the first to use remote cameras placed in unlikely

places such as ice hockey nets, or on the backboards of basketball hoops;

nobody had used blur to express rather than capture the motion of sports;

he used multiple strobe techniques to reveal the grace and complexity

of athletic movement as he did in a masterful way in a 1980 sequence

showing US Olympic diver Jenny Chandler arc through the air, enter the

pool and swim towards the camera underwater. His techniques have often

been imitated since he created them, but they have rarely been equaled,

because to John these were not merely technological tricks, but a way

of involving the reader in the action to a degree that still photography

had been unable to achieve before him. With John at a hockey match you

weren't by the ice but on it; the best seats in a Nicks game didn't

get you as close to those swirling giants as his spreads in Sports Illustrated.

With Zimmerman behind the lens you weren't just a fan, you were a fan

with access.

The one time that I worked with him at LIFE Magazine there wasn't a

remote control camera or multiple strobe in sight. What we needed from

him then was another side of his talents as a photographer. The story

was about Priscilla and Lisa Marie Presley. At the time Lisa Marie was

suffering from the double emotional burden of being a teenager and the

King's only offspring, and Priscilla was, well, Priscilla. Both needed

handling with the utmost care and delicacy, and John's decades of experience

of dealing with the super-egos of sport (as well as the models in the

swimsuit issue) came through for us big time. He was like a fly fisherman

gently luring his prey through his intense understanding of its nature.

He made them feel that his ideas were their ideas; he was respectful

without fawning, calm but determined, and exuded a quiet self-confidence.

He was how I want to be when I grow up. I wish that I'd had more opportunities

to imitate him rather than his photographic techniques.

I did have many occasions to observe and admire Galen Rowell. We worked

together at LIFE, Audubon, and on several Day In The Life books. Galen

himself was the author of eighteen books, and his company was named

after the most famous of them, Mountain Light published in 1986. After

hearing about his death I leafed through one, Galen Rowell's Vision

that is based on a collection of his columns in Outdoor Photography.

In it he reveals his secrets of taking outstanding photographs in the

wilderness. I'm sure, knowing Galen, that he did this with generous

intentions, honestly wanting the reader to be able to share his pleasures

of the outdoors and photography, because Galen was generous and honest

in all his dealings. What I don't know is whether he fully realized

that no matter how many times you read this book, even if you memorized

it from cover to cover, you would never be able to take photographs

equal to Galen Rowell's unless you had a vision and a passion equal

to his. The book is full of practical advice - "Any photo class

with more than twenty students is not a workshop regardless of how it

is promoted" - as well as philosophical advice. My favorite is

in the preface:

"My style of photography is adventure. The art of adventure is

highly participatory, but not necessarily in the physical sense of carrying

a camera to the top of a mountain to get the best picture. Even if taken

on the summit, passive snapshots made from the point of view of the

spectator are rarely considered art. The art of adventure implies active

visual exploration that is more mental than physical. The art becomes

an adventure and vice versa. Where there is certainty the adventure

disappears."

This

was the way that Galen lived his life, exploring the realms of uncertainty

in Nepal, Tibet, Africa, China, Alaska, Siberia or Patagonia. If you

look through any of his books you will see the vision of a voyager,

an explorer of lands, emotions and ideas, and in every one of them you

will see his beloved mountains. Galen made his first rope climb in the

Yosemite Valley at the age of sixteen, and he was as well known in the

world of rock climbing as that of photography. This

was the way that Galen lived his life, exploring the realms of uncertainty

in Nepal, Tibet, Africa, China, Alaska, Siberia or Patagonia. If you

look through any of his books you will see the vision of a voyager,

an explorer of lands, emotions and ideas, and in every one of them you

will see his beloved mountains. Galen made his first rope climb in the

Yosemite Valley at the age of sixteen, and he was as well known in the

world of rock climbing as that of photography.

Galen was an adventurer and he was also married to one. Barbara, his

wife of twenty one years, was a photographer in her own right as well

as an experienced and accomplished pilot who would often fly both of

them to locations or workshops in her own plane. However Galen did once

say of her: "Given the choice of a hotel room with a shower or

an icy dawn in a sleeping bag with the chance of alpenglow, she would

take the room and I would take the photograph." But the other thing

that I admired about these two wanderers was that they were both attuned

to and skilled at the business of photography. They had a gallery, both

physical and on the web, from which they sold prints; Galen wrote books,

columns and articles about photography and adventuring; they produced

posters, gave lectures and organized workshops; Galen even developed

and marketed graduated neutral density filters. They did all this while

traveling hundreds of thousand of miles per year doing assignments for

National Geographic, Outside and many other magazines. Those of you

that have read my constant pleas for photographers to take care of business

as well as photography will realize how much this endeared them to me.

For two adventurers, who regularly took risks that for many people were

outside of the imaginable, to be killed in a chartered plane from Oakland

to Bishop after returning from the Bering Sea has an irony that is painful.

For Galen to die by crashing into the majestic Eastern Sierra Nevada

Mountains is grotesque. For Barbara, the author of a book entitled Flying

South: A Pilot's Inner Journey, to end her life in a small plane that

she wasn't piloting is equally distressing.

The legacy that both John and Galen have bequeathed to our industry

is the example of being photographers of vision and uncompromising determination

who pursued their calling with honor and grace. But unless those who

will propel this profession into the future take up that legacy it will

be a hollow bequest. Emulation is not only the sincerest form of flattery,

but the best memorial that we could give them.

© 2002 Peter Howe

Contributing Editor

peterhowe@earthlink.net

|

The

word "pioneer" is one of those words like "hero"

that is used so loosely as to devalue its meaning, but if it was ever

an appropriate description of a photographer it would be to describe

John Zimmerman. Nowadays we are so used to seeing the techniques that

he invented and perfected that we forget that forty years ago they were

revolutionary. He was the first to use remote cameras placed in unlikely

places such as ice hockey nets, or on the backboards of basketball hoops;

nobody had used blur to express rather than capture the motion of sports;

he used multiple strobe techniques to reveal the grace and complexity

of athletic movement as he did in a masterful way in a 1980 sequence

showing US Olympic diver Jenny Chandler arc through the air, enter the

pool and swim towards the camera underwater. His techniques have often

been imitated since he created them, but they have rarely been equaled,

because to John these were not merely technological tricks, but a way

of involving the reader in the action to a degree that still photography

had been unable to achieve before him. With John at a hockey match you

weren't by the ice but on it; the best seats in a Nicks game didn't

get you as close to those swirling giants as his spreads in Sports Illustrated.

With Zimmerman behind the lens you weren't just a fan, you were a fan

with access.

The

word "pioneer" is one of those words like "hero"

that is used so loosely as to devalue its meaning, but if it was ever

an appropriate description of a photographer it would be to describe

John Zimmerman. Nowadays we are so used to seeing the techniques that

he invented and perfected that we forget that forty years ago they were

revolutionary. He was the first to use remote cameras placed in unlikely

places such as ice hockey nets, or on the backboards of basketball hoops;

nobody had used blur to express rather than capture the motion of sports;

he used multiple strobe techniques to reveal the grace and complexity

of athletic movement as he did in a masterful way in a 1980 sequence

showing US Olympic diver Jenny Chandler arc through the air, enter the

pool and swim towards the camera underwater. His techniques have often

been imitated since he created them, but they have rarely been equaled,

because to John these were not merely technological tricks, but a way

of involving the reader in the action to a degree that still photography

had been unable to achieve before him. With John at a hockey match you

weren't by the ice but on it; the best seats in a Nicks game didn't

get you as close to those swirling giants as his spreads in Sports Illustrated.

With Zimmerman behind the lens you weren't just a fan, you were a fan

with access. This

was the way that Galen lived his life, exploring the realms of uncertainty

in Nepal, Tibet, Africa, China, Alaska, Siberia or Patagonia. If you

look through any of his books you will see the vision of a voyager,

an explorer of lands, emotions and ideas, and in every one of them you

will see his beloved mountains. Galen made his first rope climb in the

Yosemite Valley at the age of sixteen, and he was as well known in the

world of rock climbing as that of photography.

This

was the way that Galen lived his life, exploring the realms of uncertainty

in Nepal, Tibet, Africa, China, Alaska, Siberia or Patagonia. If you

look through any of his books you will see the vision of a voyager,

an explorer of lands, emotions and ideas, and in every one of them you

will see his beloved mountains. Galen made his first rope climb in the

Yosemite Valley at the age of sixteen, and he was as well known in the

world of rock climbing as that of photography.