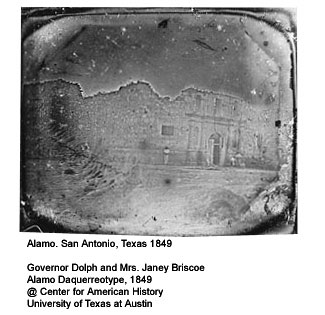

Few subjects in the United States have been more photographed than the chapel of the historic mission San Antonio de Valero - better known as the Alamo. Literally millions of people have stood in front of the picturesque limestone building with its well-known "camel's back " arch. Early eighteenth and nineteenth century artists, clerics, military personnel, and other individuals left drawings of the original Spanish mission. The 1849 photographic image provided the first substantive view of this historic structure that accurately reflected its purpose as a mission and status as a battleground. That historic1849 daguerreotype provides a very different picture of the mission in contrast to the likeness that most people hold in their memories. When I was very young at the height of the Davy Crockett craze of the 1950's, I can still recall my first visit to the building known as the Shrine of Texas history. I posed in front of the wooden entry door, probably in my Fess Parker coon skin cap. I undoubtedly imagined myself one of the brave defenders of the desperate fight in March 1836. I also recall my disappointment upon entering the chapel. I fully expected to see dried blood, bullet fragments and wreckage from the battle. Instead, it was like going into church on Sunday. Well-dressed guides instructed men and boys to remove their hats. No one spoke above a whisper. The polished floors and pristine surroundings truly confounded the perception that I obtained from the movies and the Disney television series. But the famous hump back outline of the historic mission stood tall and irrefutable - or so I believed. Thanks to Hollywood and Kodak, that is the image of the Alamo that most people hold today. The eighteenth century Franciscan chapel survived more than a century of hurricanes, floods, epidemics, hostile Indians and, finally, secularization and distribution of the mission's assets to the local community. In the early 1840's, bats and owls inhabited the former mission and battlefield. The ruins also attracted the young boys of that era who played among its crumbling walls. The U. S. Army probably saved the abandoned structure when it turned the place of worship into a quartermaster storage building in 1846. (It's hard to fathom that hay and hardtack were housed in the same rooms that witnessed Christian rituals and bloody combat). In addition to altering the mission's purpose, the army significantly changed the building's architectural design. In San Antonio today, businesses that range from restaurants and high tech firms to veterinary clinics and body shops use the image of the Alamo for their business logos. In John Wayne's The Alamo, the actor duplicated the army's modified version of the mission when he reconstructed the chapel for the film. The icon is so firmly entrenched in popular culture that even a descendant of a martyr of the Alamo would hesitate to recommend a modification that would revert to the original structure. Thanks to an entrepreneurial photographer who captured the image of the old mission, one of the most historic buildings in American history is now preserved for future generations. E. P. Whitfield, the only photographer who advertised his services in San Antonio, Texas in 1849, may have taken the daguerreotype. The daguerreotype was still a relatively new phenomenon in those years, especially in the western areas of the nation. The process of capturing a silver-mercury image on a thin sheet of silver-plated copper was cumbersome. Yet daguerreotypes became popular formats for recording a visual history for the young nation in the years before the Civil War. Thanks to E. P. Whitfield and other early photographers, we have documented visual evidence of important national landmarks and individuals. And because of the generosity of former Texas Governor Dolph Briscoe, Jr., the landmark Alamo image is now located at the Center for American History. This 1849 daguerreotype represents more than the portrait of a single historic structure in the American Southwest. The Alamo and many other historic sites play a dual role as part of our national heritage and our collective imagination. Photographers and photojournalists from the earliest days of the profession understood the importance of capturing visual images of significant places and events. Photographs provide an invaluable resource to historians who seek to understand everyday life and events of a bygone era. People from all walks of life take an active interest in exploring the past - especially the areas and places that are threatened with deterioration and destruction. These visual images shape and define our collective memory as a people and a nation. So as we say in Texas: Remember the Alamo - especially the way it used to be. © Patrick Cox, Ph.D

|

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

T

T Shortly

after Texas became a state in 1845, the U.S. Army occupied the Alamo.

After the 1849 daguerreotype was taken, the army significantly changed

the structure's outward appearance. Second story windows and a new roof

were added. The most striking alteration was the addition of the distinctive

curved gable at the top of the church façade that became popularly

known as the camel's back. The army, in conjunction with their extensive

military contracts, literally changed the face of the American west.

The U. S. military blazed trails, pushed Native Americans onto reservations,

and established permanent communities. Their actions helped determine

the structure of the present day American west where guided missiles

have replaced mounted cavalry. Nothing is more symbolic of this impact

than the alteration of the oldest missionary structure in this part

of the nation.

Shortly

after Texas became a state in 1845, the U.S. Army occupied the Alamo.

After the 1849 daguerreotype was taken, the army significantly changed

the structure's outward appearance. Second story windows and a new roof

were added. The most striking alteration was the addition of the distinctive

curved gable at the top of the church façade that became popularly

known as the camel's back. The army, in conjunction with their extensive

military contracts, literally changed the face of the American west.

The U. S. military blazed trails, pushed Native Americans onto reservations,

and established permanent communities. Their actions helped determine

the structure of the present day American west where guided missiles

have replaced mounted cavalry. Nothing is more symbolic of this impact

than the alteration of the oldest missionary structure in this part

of the nation.