No Easy Witness

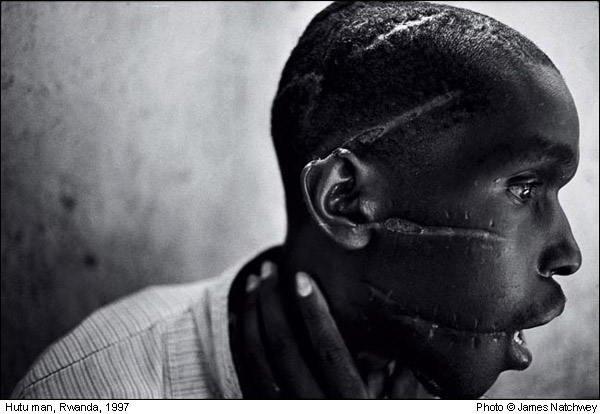

It’s not easy to witness another

human being’s suffering. There’s a deep sense of guilt—not

that I caused the situation, but that I’m going to leave it.

At some point, my work will be finished, and if I’m lucky, I’m

going to get on an airplane and leave. They’re not.

It’s a hard thing to say, but

there’s something a bit shameful about photographing another

person in those circumstances. None of this is easy to deal with,

but overcoming emotional hurdles is just as much part of being a photojournalist

as overcoming physical obstacles. If you give in, either physically

or emotionally, you won’t do anybody any good. You might as

well stay home, or do something else with your life.

People understand implicitly that when a journalist from the outside

world shows up with a camera, it gives them a voice they wouldn’t

otherwise have. To permit someone to witness and record at close range

their most profound tragedies and deepest personal moments is transcendent.

They’re making an appeal; they’re crying out and saying,

“Look what happened to us. This is unjust. Please do something

about this. If you know the difference between right and wrong, you

have to do something to help us.” It’s that simple, that

elemental.

James Nachtwey: Born in Syracuse

New York in 1948, and a graduate of Dartmouth College Nachtwey came

to photography after a series of unrelated jobs, including a spell

in the merchant marine. Self taught as a photographer he started his

career on a local newspaper in New Mexico, and subsequently joined

Black Star in New York. He has covered conflicts since 1981, and has

received the Robert Capa Gold medal five times, the World Press Photo

Award twice, and is a founding member of the agency VII.