The Woman Behind the Girls January 2003 I don’t

like Los Angeles. I don’t like the fact that it’s a company

town; I don’t like its values; I hate the Freeways, which

to my mind are neither free nor ways I don’t like the architecture,

not that there is a lot there that could be endowed with the categorization.

I don’t even like the weather that much. I don’t know why

Angeleans are always going on about it. For nine months of the year

the air is literally unbreathable, and for me air is a part of the weather.

Just because it’s warm unbreathable air doesn’t make it

more acceptable.

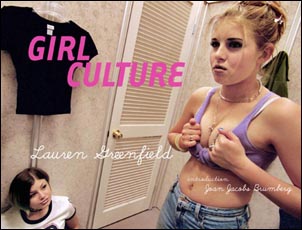

But what I hate most about Los Angeles is that it keeps coming up with redeemable features that don’t comfortably fit into my prejudice against the place. My favorite client’s business is there, and at least six of my favorite photographers live and work there. These are people like David Strick, Gerd Ludwig, Douglas Kirkland, Jim McHugh and George Steinmetz, all smart people, so there must be something about the city that I don’t see. In fact the last time that I was with the above was at the gallery opening of another of my all time favorite shooters, Lauren Greenfield. The exhibition that we attended was of the work that Lauren produced for her latest book, Girl Culture, and which reinforces her position as one of the foremost social documentarians in contemporary American photography. She has three qualities as a photographer that I admire. First of all she refuses to waste her time complaining about the state of documentary photography, but finds ways to make a living and do the work that she is compelled to do; secondly she realized early on that traveling to far-off, exotic places to photograph cultures she didn’t understand was less valuable than recording the quirks and foibles of her own environment. The third quality, of course, is that she produces photographs that are so on target they often seem like an arrow to the heart. In fact her earliest influences were social observers who also concentrated on revealing their own surroundings. In Junior High she saw, and was impressed by, shows of the work of Henri Cartier Bresson and Gary Winogrand. Significantly Lauren’s initial education was not in photography but social studies, which she took at Harvard. In the third year of this course she was one of thirty students who traveled to nine countries around the world to study visual anthropology of the different cultures to which they were exposed. Professors of film and anthropology accompanied them. She stayed with families and studied in the Ethnographic Institutes and film schools in places such as Hungary, India, Australia, and it was during this year that she decided that she wanted to take culture as the subject of whatever her career was to be. Thankfully for us, Harvard would not allow her to combine her growing interest in photography and film with social studies, and so she changed her major to visual studies, which she felt would allow her more direct contact with cultures instead of the theoretical approach of her education up to that point. She was more attracted to documentary filmmaking, partly because she could not see a role for her in photography that would be more than just illustrating other people’s writing. However, upon graduation she applied for and received a grant from Radcliffe to work on a project on the French aristocracy. When she was fourteen her mother, a professor of psychology, had taken a three month sabbatical to live in Paris so that her daughter could learn French. Lauren so liked the school that she attended there, and wanted to become fluent in the language that she remained after her mother returned to the States. The family she stayed with was a part of the aristocracy who took in students for additional income. Lauren was fascinated by the concept of impoverished aristocracy, especially coming from Los Angeles where social hierarchy was determined by wealth. Upon her return that the small grant made possible, the same family facilitated the entrée that she needed to begin to document the mores of this class, and especially the social rituals that bind them more tightly than money, and which gives them their cultural identity. The work she produced during this time can be seen on the VII web site. This work also contributed to what was to become her first big break as a photographer. Having struggled in New York trying to do documentary films, and after a period as a receptionist and desk assistant at ABC News, she applied for an internship at the National Geographic. The magazine happened to be working on a major issue on France to celebrate the bi-centennial of the revolution, and she had presented the French work as a part of her application. She was accepted, and the three months that the internship lasted had a profound effect on her. She was exposed to the work of James Nachtwey’s story on Pollution in Eastern Europe, Alex Webb’s photography from South America, and Gilles Peress’s essay on Simon Bolivar; she hung out with the Geographic photographers, including listening to David Doubilet playing the banjo in the office next to hers; she could use as much film and equipment as she wanted, and got to show the results of this use to the director of photography for feedback. It was a failure at the Geographic that finally put her on the course that has proved so fruitful for her to this day. About a year after she finished her internship she proposed a story to them about the Maya Indians in Mexico. The writer on the piece was to be her mother, who had done field work in a village in Chiapas twenty years before as a part of the Harvard Chiapas project. National Geographic accepted their proposal, and mother and daughter worked on it for four months. The story never ran, and was a struggle from the start. Lauren had to deal with technical difficulties bred of inexperience, as well as huge problems of access. Even though her mother had a twenty-year relationship with one family, which was an advantage, there was the belief among the Indians that to photograph someone is to steal their soul. Also as a woman Lauren could only deal with the women of the tribe, who spoke no Spanish, so she set about learning the Mayan language. The biggest problem however was that she did not understand the culture that she was photographing. She was an outsider who could only scratch the surface in the time that she had available. She returned briefly to the United States in the middle of the story to attend the Eddie Adams Workshop in 1991, and it was here that she met the next big influence on her career, Sygma’s Eliane Laffont. Each year at the workshop Sygma would give an award to the most promising student, which consisted of funding a project of the winner’s choice. That year it was given to Lauren, and after the frustration of the Maya story she decided to work in the culture that she knew best, the teenagers of her hometown. She felt that she could bring her own perspective to this subject based on her teenage experience, whereas even the best pictures she had taken in Chiapas seemed to her as if they could have been shot by any photographer standing by her side. This project, which she worked on for the next four years, was to become her first book, Fast Forward – Growing Up in the Shadow of Hollywood. In the preface she writes: “By exploring my own culture I could begin with a level of access and understanding impossible elsewhere after the most extensive research and field work.” While in Chiapas she had found, and re-read a dog-eared copy of Less than Zero, Bret Easton Ellis’s bleak novel about the excessive, drug oriented culture of the children of Los Angeles wealth. During a period of time in England with her husband Frank Evers she had observed the teenagers of that country watching Beverly Hills 90210. Upon her return home she became increasingly aware of the influence of MTV upon teenage culture, and the desire of the children of privilege to emulate the poverty bred violent society of Hip Hop and the ghetto. Although Sygma provided the initial funding to get her started, it was once again National Geographic that supplied the long term funding that she needed. Even after her work was finished it still took another two years and thirty rejection slips to find a publisher at Knopf through Charlie Melcher of Melcher Media. The book was a stunning achievement for someone of her age, only thirty at the time of its publication. It is a profound look at superficiality, and a revealing demonstration of the loneliness and aimlessness of the existence of both the wealthy and the poor whose lives are dominated by the shadow of Hollywood both culturally and geographically. Looking through its pages you no more envy the children of Malibu and Bel-Air than you do the gang members of Southeast Los Angeles. Fast Forward was a turning point in her career that she describes as “a complete fantasy dream come true.” She went from being a struggling photojournalist trying to make a living through whatever assignments she could get, and spending her own money on the project when National Geographic’s ran out, to winning the ICP Infinity Award for Young Photographer, and a sharing a show there with the work of Helen Levitt. Fast Forward also led directly to her second book published in 2002, Girl Culture. In her own words Girl Culture is an investigation of “the social and emotional development of girls and their interaction with pop culture and the material world.” She also feels that the second book is much more personal that Fast Forward, in which she was still fulfilling the role of the cultural observer. Although she grew up in that world she was not a part of it. Her parents were both professors, academics who played no part in the entertainment industry that was the environment of so many of their neighbors. Girl Culture on the other hand is passionately driven from her own experiences as a teenager and indeed her life as a woman today, and as a result she feels that it is much more emotional than the intellectual approach that she took in Fast Forward. Lauren feels that the experiences of the teenage girl stay within many women and that there are important relationships between marginal subcultures and mainstream culture. With popular culture acting as a conduit, she looks at the connections between the stripper, the showgirl, and a pop star like Jennifer Lopez, and the exhibitionism of a suburban teenager or a little girl playing dress-up. As she puts it “The body has become the primary expression of identity for girls and for women, and a lot of the things that I was looking at, they don’t stop when you become a woman.” It was not remarkable that the last time I saw Lauren was at her gallery opening. Shows of her work in environments such as the Stephen Cohen Gallery on Beverly Boulevard have been an important tool in getting exposure for her work. Museums and galleries have been a venue for her work since she established herself in the fine art world with the publication of Fast Forward. Her photographs have since been acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the San Francisco Museum of Art, and a number of other museums. She has produced a traveling museum exhibition of Girl Culture because she thinks that through museums she is more likely to reach the young audience for whom she feels her work will have value. Her attitude is that teenagers are unlikely to pay $40 for a coffee table book, rarely read Time magazine, the National Geographic or even People, but they are frequently taken to museums on school outings. In fact some of her most important feedback from Girl Culture has been from exactly this source. Not only letters that she has received from schoolchildren, but also anecdotes from the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson Arizona, who will house a considerable number of prints from the project, and are responsible for touring the show. One of the men working as a docent there told her the story of a male student from the University of Arizona who made a salacious comment about a picture of a young model removing her bra during a photo shoot on Miami Beach. After seeing the rest of the show he came back to the docent and apologized for the comment. She herself heard a boy visitor to the museum say that he felt nauseous after seeing the work, and realized how badly he had treated the girls at his high school, and how complicit boys were in the process. The late Arthur Ashe once advised: “Start where you are; use what you have; do what you can.” If any photographer conforms to these principles it is Lauren Greenfield. We all understand how difficult the market for photojournalism is today; we all know how few serious pictures ever reach the printed page; we see a profession that appears to be slipping from our grasp. Yet in the same world that everyone finds himself or herself Lauren has single mindedly and with intense focus carved out her position in contemporary photography. She has done it by understanding her subjects and themes, but as importantly understanding what she must do to be able to complete the projects that are so important to her. This has ranged from waitressing when she needed to print the photographs from her French Aristocracy project, to shooting fashion and commercial work today. She understood early on the time ratio between shooting photographs and ensuring the means to shoot them. She has fought for grants, fought for publishers, fought to be her own woman in photography. We could do with more girl photographers like her. Greenfield on: Grants A lot of times grants have been a way for me to have the confidence to do something. There is a validation to getting a grant and also a responsibility. Somebody gives you something and then you have the impetus to produce. But definitely the validation because I think when you are doing documentary photography in a lot of ways it’s a very existential process where you don’t really know if anything you do is going to come to anything. It’s not like a job where you are being paid and you know that you’re doing something that you have to do. Taking a Point of View I think in Girl Culture there is a point of view and I would be dishonest in saying my point of view doesn’t come strongly through. The point of view gets developed in the conception of the book, in the conception of the project, but not at all when I’m taking pictures. When I’m taking pictures I’m just there, and I’m not looking for a particular thing, I’m really just interested in the people I’m photographing. If you’re too pre-determined the pictures are too forced and people can detect that manipulation, so I go into the situation with a very open mind. I think that one of the powers of documentary photography is that you can have a point of view, and you can even have a strong point of view, and most viewers of the picture are going to respond to it as though it’s completely objective reality and they’re just seeing it for the first time and not really be aware of the way that you’re having them see it.

One of the things that I feel very lucky about is that I’ve come up at a time where the strict boundaries between different kinds of photography have broken down The New York Times Magazine will commission fine artists and they’ll commission photojournalists and fashion photographers. People like Nan Goldin have broken down some of these boundaries. I’m not really looking to make a name for myself in the fine art world to the exclusion of something else. I guess with Girl Culture I just tried to do everything at once. Frank calls it the Multi Platform Release! Magnum’s Longevity I was talking to David Allan Harvey about Magnum, and he was saying that their accountant looks at the whole business plan and throws up his hands, but on the other hand has some respect that this place has been around for a long time. A lot of businesses have come and gone, and Magnum still survives. I think we [the agency VII] will be lucky to be in business as long as Magnum is. I have great respect for Magnum and the work that they’re doing. Despite the problems it still works. I was with Sygma a long time and last year was the first time in fourteen years that Sygma wasn’t even at Perpignan. Editorial Work Editorial work is the creative life blood of my personal work. It gives me a discipline and a rigor that I don’t always have when I’m completely self-motivated. It often just gets me into things where I make discoveries that maybe bring me back to projects I was already working on but I wouldn’t have known to go there. I guess the sad part of the equation is that it would be nice if I could just make a living doing editorial work, that’s really how it should be. If you’re working enough you should be able to sustain yourself that way. I have the added complication that I’m a working mom, so sometimes I’m going on the road with a baby sitter, and then I’m really looking at a break-even situation. I look at being able to create the work, and then see at what the outlets are, and be creative about the outlets. Once the work is created then there’s resale in Europe, there’s the fine art world, there’s using this work to get commercial work. I think the main thing, and I think it’s especially important for young photographers, is to figure out a way to do your own work, and do your own projects and find your own voice. The Next Project Reza told me a couple of years ago at a dinner party in Paris that when people ask you “What’s your next project?” you have to say “that empties your emotions.” It’s better in French: “ça vide les emotions.” But I think that’s true. I’ve told people in the past and sometimes it blocks you. But I want to do a project that’s not necessarily about youth, but definitely continuing the same theme, a continuation of Girl Culture and Fast Forward. I always think of what the French filmmaker Jean Renoir said about every film is the same film © Peter Howe, 2003 |

Enter GIRL CULTURE

Camera: David Snider

|

|

| Girl Culture Video | Hi Band |

Low Band |

Buy the Book: Girl Culture

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |