And you may find yourself in

another part of the world… Indeed. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Happy New Year. I always get a bit

pensive this time of year. Work is inevitably slow and I have too much

time to think. January marks a few exciting events—my birthday

(Joy! Almost forty and still all alone with a tenuous career and zero

financial stability), the hanging of the new wall calendar (Dr. Seuss

this year/Because I fear/The year shall be sad/With the War Against

Bad), and the anniversary of my arrival in Egypt. “A big plane,” I reply. I came to Egypt in January 1996 with a job as a photographer for a local publisher who produces several English language feature magazines. I planned to stay two years. Somehow, I lost track of time. Two years quickly turned to seven— with no end in sight. Same as it ever was…same as it ever was…

“Freelance' is an appropriate term. The free lance—the mercenary knight or roving soldier available for hire. That’s me—a condottiere, a camera for rent, available for the highest bidder—any bidder for that matter. Mine is the same old story many freelancers will tell. Work was sporadic in the beginning, and I wound up doing very strange things for money—all of them legal—hell, anything to pay the rent. I photographed hotels and resorts. I photographed factories and potato chip bags. I photographed banquets and functions. I wrote corporate propaganda. I did voice-overs for CD-ROMs and in-store promotional tapes. I almost got to sing the jingle for a television toothpaste commercial. Thank God I couldn’t hit the high note. “Isn’t it tough being a woman photographer in Egypt?” Yes. And no. It’s much like being a woman photographer anywhere on the planet. I get my share of condescending treatment from men, or bewildered stares from men and women alike when I am bashing around with the photo-boys, my 12 kilos of camera gear dangling from my neck and shoulders. Foreign women are Jennifer Lopez, Julia Roberts and Madonna all rolled into one. Don’t mind her bold, unfeminine behaviour, she’s a khawaagaya (foreigner). Your sister is not supposed to live alone and party until 2am, but we know about those foreigners. After all, we have satellite TV.

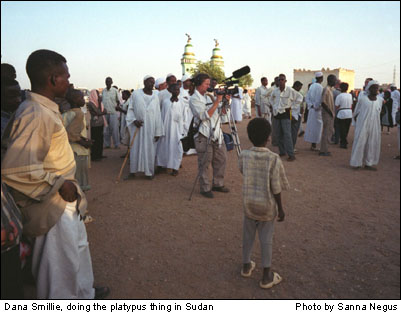

I am also welcome in the circle of women. It’s not always photographable, but it is a barrier my male colleagues cannot always pass. One day a few years ago, I was working with a woman newspaper correspondent in Gaza. It was Friday around noontime, and our fixer wanted to go to the mosque to pray. A veiled figure appeared in a doorway and waved us inside. We could wait with her. As soon as the men left, off came the veil and this demure silent figure transformed into a lively animated woman wrangling two active small children and talking politics and current affairs. The men returned from the mosque, she disappeared into the back room and reemerged as the veiled figure we first encountered— silently serving tea and hovering in the background while the correspondent and I sat with the men. Even though I am an honorary man, at the end of the day I am just a harmless girl in the eyes of most people. Foreign photographers are viewed with great suspicion in Egypt, as the general public is very concerned about the image being projected in the West. My male colleagues have endless stories about heated encouters with people on the street or security officials who object to what they are photographing. (Who are you? Who do you work for? Don't you know that photographing this is forbidden??) My encounters are generally more personal (are you married? do you have any children?? NO?? why not??). As if I could not possibly be doing anything more serious with a camera than taking snapshots to entertain the ladies at next Wednesday's housewives coffee club, right? And you may ask yourself, How do I work this? I started dabbling in video after finishing the Platypus workshop in March 1999. I did the occasional web or CD-ROM job until the dot-com crash and the economic downturn in Egypt. By coincidence, I got a chance to work in television in November 2001. A Cairo-based correspondent for the Finnish national television was preparing a story about the woman’s metro car and thought it might work better if she had a female cameraperson. Not to many women running around here with full betacam kit, so she was willing to take a stab at a Platypus. The partnership clicked, and we have shot and edited 18 features since then, including four stories from Khartoum. We are a two- woman band, hip to the ways of the region, and can travel cheaply and effectively. Despite the fact that I record voice-overs by making the correspondent crawl into a cave of blankets an carpets that I build under my dining room table to reduce the echo from the high ceilings, the network bosses seem to like our work. And you may ask yourself, Where does that highway

go? After the events of September 2001, work shifted almost exclusively to visual journalism (Joy! No more hotel lobbies!! No more corporate copy-editing! No more factories!). Suddenly, every journalist in the world seemed to be coming to the Middle East with a short junket to Cairo. Occasionally, they needed a photographer. Or at least they bought me a beer and passed along my phone number to someone who did. “Hallo?” They came and went—to Pakistan, to Afghanistan, to Badistan and Bigstorystan. I stayed here and covered the demonstrations and the Arab street reaction pieces. I had always been a loner, a feature-girl, but suddenly I was running around with the pack. The wire boys told funny stories and showed me which way to run when the tear gas canisters were shot. At the end of the week, though, our demonstrations were never as Bad as the others, so it was hard to move pictures. Unless there’s a fire in Cairo, nobody seemed to care. Let’s face it. The Big Story is never here. It is always just out of my grasp. I suppose I could ‘go for it’—just turn up at the hot spot d’jour and hope for the best. But turning up these days requires a satellite phone and a pocket full of $100 bills, something that is usually in short supply around my house. Indeed, how does the errant-mercenary-knight-platypus compete with the Wire and Network Battalions? I do get bored, and from time to time have ventured

off once or twice on my own with no assignment, to hot spots that have

cooled off a bit, or soon-to-be hot spots that are smoldering and waiting

to explode. I wind up taking pictures that nobody needs. Right place,

wrong time. Stop whining. Life is good. I have had some great assignments

in the last few years, worked with many excellent writers, correspondents

and crews, met some fascinating people and got to climb to the top of

the Great Pyramid. The career is moving along—slowly but surely—at

least I don’t have time to audition for toothpaste commercials

anymore. It’s just a bit frustrating sitting in the stands while

the World Series is being played in your back yard. I stopped making long term plans. Sure, I think about the future and where I would like to be in my career and life in 5 or 10 year (a house on the Chesapeake bay, a fat precocious cat, a month free every year to hide out in India and practice yoga, and steady work shooting and producing feature documentaries on Africa and the Middle East for the other eleven). I learned very quickly one sweaty afternoon in

September that plans are meant to change at the drop of the hat. So

much for my passionate need for order. Wait and see. Stay or go. Take

things as they come. © Dana Smillie |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

Since

1999, I have been freelance photographer/video cameraperson and occasional

writer. It seemed like a good idea at the time to set up shop in Cairo.

I knew my way around town. I had secured a cheap place to live with

amazing high ceilings. I had a few clients. I had a lot of friends.

Since

1999, I have been freelance photographer/video cameraperson and occasional

writer. It seemed like a good idea at the time to set up shop in Cairo.

I knew my way around town. I had secured a cheap place to live with

amazing high ceilings. I had a few clients. I had a lot of friends.

Foreign

women have an interesting social position. We are “honorary men”.

I can hang out with the men and smoke cigarettes and talk politics while

invisible women prepare tea or lunch. I can disappear in the desert

with a Bedouin guide and nobody thinks twice. I can spend the morning

trudging through open sewers in a slum area, and the afternoon photographing

a top government official.

Foreign

women have an interesting social position. We are “honorary men”.

I can hang out with the men and smoke cigarettes and talk politics while

invisible women prepare tea or lunch. I can disappear in the desert

with a Bedouin guide and nobody thinks twice. I can spend the morning

trudging through open sewers in a slum area, and the afternoon photographing

a top government official.