| Larry Burrows:

Vietnam

February 2003

by David Halberstam |

|

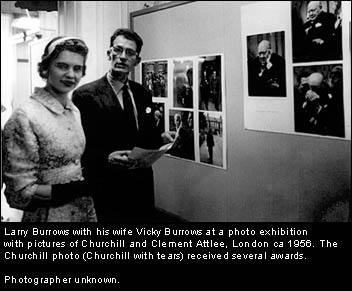

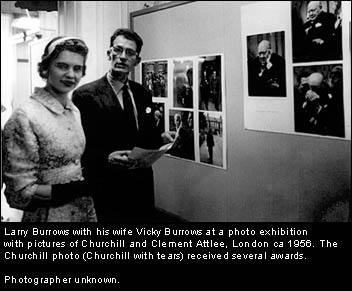

Larry Burrows

first went to Vietnam in 1962, when the war was still very small, and

for the Americans at least (if not for the Vietnamese, who had been

fighting in some form or another since 1946), still very young. He was

thirty-six when he first arrived, just entering his professional prime,

and it was the assignment he had always wanted. He had been too young

for World War II. He was twenty-four in 1950 when the Korean conflict

broke out, and he had tried desperately to go, but had been judged too

young and too junior in Life’s pecking order. Vietnam, therefore,

was going to be his war. He got there early and staked it out from the

beginning, telling his wife, Vicky, that he was going to stay to the

end and cover it until there was peace. He was hardly green at the time—he

had been photographing as a professional for Life for more than a decade,

he had covered violence in the Middle East and the chaotic tribal fighting

in the Congo—but this story was going to be his own and he was

going to see it through.

Because of that vow, along with his talent, his courage, and his particular

feel for the Vietnamese people, he became the signature photographer

of that war, a man whose journalism, in the opinion of his colleagues

and editors, reached the level of art. He would stay in Vietnam for

nine years. More than any other photographer and print journalist, his

work captured the different faces of the war; for those of us who were

there, opening this book brings the shock of recognition of scenes,

some of which took place nearly forty years ago and are now almost forgotten.

On one occasion, around 1969, after some seven years there, he had come

back to New York and was visiting with his Life colleagues. Someone

asked him how the war was going. “Well, you American chaps have

quite a problem there. Thank God it isn’t my war.” “Larry,”

said Ralph Graves, who was one of his editors, “if it isn’t

your war, whose is it?”

Vietnam at the moment of his arrival was not yet that big a story, though

it was soon to be the most important story in the world and to stay

that way for nearly a decade. The Americans were not yet in a combat

role and were still serving as advisers to the South Vietnamese Army,

or ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), as it was known. Larry Burrows

was pulled to it from the start; he understood that this struggle had

only begun, and that it was going to be, whatever the outcome, a bigger

war and a much bigger story than anyone back in New York realized. I

think he understood the unusually bitter quality of it because it was

a civil war; it is in the nature of civil wars to be especially cruel

and ugly. You can see the evidence of that in some of his very early

photos of Vietnamese tormenting Vietnamese. He also knew the one great

truth that the early generation of journalists and photographers who

went there understood: that given the particular nature of this war—small

units fighting all over the country—it was going to be, if you

figured out how to go and look for it, amazingly accessible for a photographer.

Vietnam at the moment of his arrival was not yet that big a story, though

it was soon to be the most important story in the world and to stay

that way for nearly a decade. The Americans were not yet in a combat

role and were still serving as advisers to the South Vietnamese Army,

or ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), as it was known. Larry Burrows

was pulled to it from the start; he understood that this struggle had

only begun, and that it was going to be, whatever the outcome, a bigger

war and a much bigger story than anyone back in New York realized. I

think he understood the unusually bitter quality of it because it was

a civil war; it is in the nature of civil wars to be especially cruel

and ugly. You can see the evidence of that in some of his very early

photos of Vietnamese tormenting Vietnamese. He also knew the one great

truth that the early generation of journalists and photographers who

went there understood: that given the particular nature of this war—small

units fighting all over the country—it was going to be, if you

figured out how to go and look for it, amazingly accessible for a photographer.

That view went against the prevailing attitude of most of the photographic

stars from the previous era who had made their reputations in World

War II and Korea, and who more often than not judged Vietnam not worthy

of their talents. (One notable exception was Robert Capa, who had gone

to Indochina in 1954, late in the French war. On arrival Capa had toured

the country and then told John Mecklin, the young American reporter

with whom he was working, that it was a major mistake for the great

professionals of World War II to put down this war. Scale did not matter,

Capa said, and besides, this war had everything: great drama, great

access, and above all, it placed great faces on the fighting. Shortly

after he said that, Capa was killed by a Vietnam land mine in the Red

River Delta.)

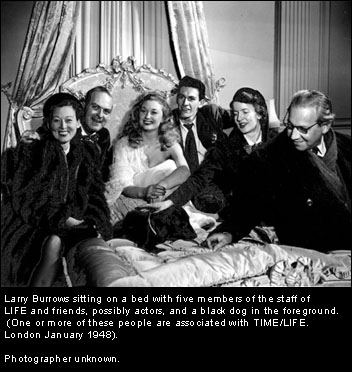

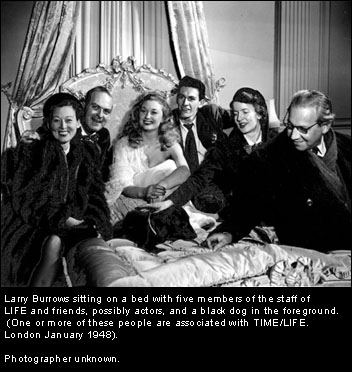

Larry Burrows was not to the manor born, nor did he start at the top.

On the way to becoming the best of the best, his was a long, difficult

apprenticeship. His father was a truck driver for the railroad system,

his mother a housewife. He never went to college. Instead, in 1942,

at the age of sixteen, he got a job in the lab in Life magazine’s

London bureau. He was a gawky kid, unsure of himself, with a terrible

stutter. He became a kind of lab rat, an all-purpose gofer doing all

the tasks that no one else, certainly none of the stars, wanted to do,

drying the film and running errands for the giants who were shooting

the war—including Capa, whose film he processed. “Our darkroom

tea boy,” Honor Balfour of the London bureau once called him,

because among his other duties, he was to line up at the canteen and

get coffee and tea and cheese rolls for his seniors in the office.

Though he intended to go into the service and become an Army or Navy

photographer, his eyesight was so poor that the military rejected him,

and he was conscripted by the government to work in the coal mines,

something he hated. Whenever he returned to London from the mines, noted

Ms. Balfour, his stutter was much worse. She became convinced that much

of the humanity that was eventually reflected in his photographs grew

out of that experience. The mines, she believed, “burned into

him a hatred of suffering and forged a courage that carried him into

the most dangerous situations in the world.” In time he was invalided

out of the mines, and he returned to Life’s darkroom, where he

printed thousands of pictures taken by the great photographers of World

War II.

So Vietnam was what he had long been waiting for. He was drawn to it

by both its elemental humanity and its parallel cruelty and violence,

and by the fact that it lent itself so well to what he wanted to do—the

magazine photo spread, which Life more than any other magazine had not

only pioneered but had made its specialty. From the start, the best

photos from Vietnam were his. He had a feel for the war and the people

fighting it, for the special texture of it, and he understood as well

that if you were going to be a photographer for a great photo magazine,

this was the ultimate assignment, demanding the ultimate risk, for the

two could not be separated, opportunity and risk.

He understood Vietnam’s special possibilities for a photographer

who worked for Life: you had the luxury of time (and space); you could

hang out with the troops and get to know them; and sooner or later,

if you spent enough time in the field, if you did not find the war,

then the war would find you. Other photographers, based as he was in

Saigon but more often than not working for wire services—journalistic

institutions that demanded far greater immediacy—were always on

deadline. They regarded him enviously: a major operation would be launched,

a plane or helicopter would ferry them from Saigon to the battle area,

they would shoot as quickly as they could, and then they would rush

back to Saigon, hoping to get their photo on the wire and beat their

rivals. Perhaps if they were lucky they were able to get one or two

exceptional pictures; but their work was not rooted as Larry’s

tended to be. Larry used this luxury exceptionally well. He did not

like to work as part of a pack—he was a loner by instinct. He

would spend time in Saigon listening to his colleagues, trying to figure

out where the good (or hot) areas were and what was at stake, trying

to decide what he wanted to portray. And then he would go into the field

by himself, settle in, and wait for the action. In time, he developed

an almost perfect sense of what was at issue in the war at that particular

moment, and what it was he wanted to shoot. Sooner or later it would

all happen, and he would have his story.

What

he represented is historically important: the last great photographer

shooting an evolving war that was becoming more violent almost by the

day for a great and deeply influential magazine (which was week by week

and month by month becoming weaker and less influential). Even as he

worked, the importance of still photography was being muscled aside

by the coming of network television as the prime visual means of communication,

in what was the first television war, or in Michael Arlen’s apt

phrase, “the living-room war.” Larry arrived when reporters

and photographers were still part of what was called the press, and

not yet “the media.” What

he represented is historically important: the last great photographer

shooting an evolving war that was becoming more violent almost by the

day for a great and deeply influential magazine (which was week by week

and month by month becoming weaker and less influential). Even as he

worked, the importance of still photography was being muscled aside

by the coming of network television as the prime visual means of communication,

in what was the first television war, or in Michael Arlen’s apt

phrase, “the living-room war.” Larry arrived when reporters

and photographers were still part of what was called the press, and

not yet “the media.”

In 1963, he made what was his real Vietnam debut, his first major, long

photo essay, which appeared in Life in January of that year. Much of

that unprecedented fourteen-page story is reproduced in the opening

chapter of this book. In effect the essay introduced both Larry and

the war to millions of American readers. It is brilliant and disturbing

storytelling. There are a number of photos in it that are especially

jarring and which back in those more innocent days helped trigger a

certain uneasiness among ordinary Americans back home: a South Vietnamese

soldier holding a knife, towering over a cowering and terrified Vietcong

soldier whose hands are bound; Vietcong prisoners, their hands bound,

being herded into a sampan; South Vietnamese troops moving through a

village, a hut burning in the background. “We Wade Deeper into

Jungle War” was the article’s prophetic subtitle.

It was the kind of storytelling which set Burrows’s work apart.

Another factor that made his work so exceptional was his stunning use

of color. Here he was a pioneer, far ahead of his contemporaries in

understanding how to use it. He had learned the hard way, through an

exceptionally taxing apprenticeship. For Life had sent him to Europe

as a young man to do a job that had seemed at first almost menial, to

help in a project that was to reproduce great artworks in the magazine.

In the beginning he had worked with Dmitri Kessel, and then in time

he took over the assignment himself. It was a transforming experience.

He learned how great artists saw their work, and he became expert in

bringing the true color of a great painting through to the pages of

the magazine. He understood as well that when the conditions were right,

color cast a special glow around the core of a photo, and created its

own living ambience. Color, done right, was mood; mood, done right,

became art. Some of that is clear in a note he wrote to his editors

relatively early in the war: “I am very happy with the equipment

I have. All I need is time and patience to use it to the fullest degree,

plus God on my side to help with the lighting problems—to move

the sun and the moon and the stars to the positions of my choice.”

He did not like to shoot black and white and color at the same time,

because the best conditions and lighting for each were so different,

and the effect of the photos was so different. “He was not like

all the other photographers of that time when they shot color,”

said his good friend Horst Faas, the distinguished Associated Press

photographer. “The others tended to take the same photo twice,

and the second time, instead of black and white film they used color—so

the same people turned up in both photographs. Color was very different

for Larry. He understood what it could do the way a great artist understands

it and he used it like an artist—as if he were one of the Impressionists.”

The results of that rare talent are evident in this book, in some ways

hauntingly so.

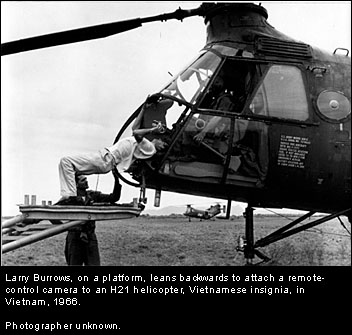

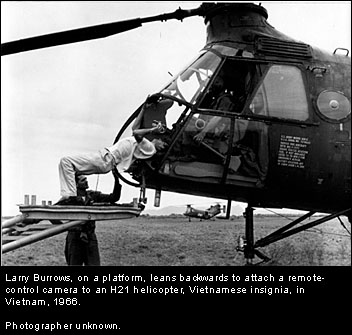

He once talked the Vietnamese Air Force into taking the doors off a

fighter-bomber so he could lean out and shoot as if he were virtually

outside the plane—shooting color, of course. When other photographers

asked for the same privilege, they were turned down. When they complained,

they were told by the authorities, “Mr. Burrows’s request

was granted not because he is a photographer but because he is an artist.”

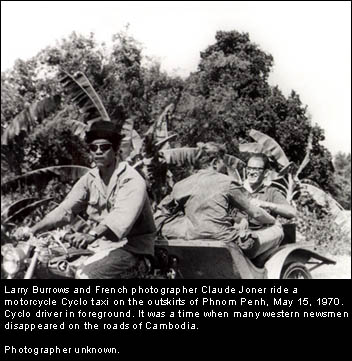

Larry, like the rest of us who covered Vietnam, had no idea how long

the war would last and how infinitely more violent it would become,

consuming us not just physically but psychically as well. It would be

the defining experience of our lives, and in his case, it would take

his life. But he always knew the risks. Everyone there did, especially

the photographers. We print people always knew that we could show up

after the battle and by dint of our skills we could reconstruct what

had happened. But the photographers had to be there, right at the scene—arrive

a little too late and it was over. No one was there more often and got

up closer than Larry. He was, said his Life colleague David Snell, either

the bravest man in the world or the most nearsighted, because he pressed

himself so close to the very edge of battle again and again.

He

knew of course that he was not immune, that the risks were always there.

He told Vicky that the camera made him invisible, that the other side

could not see him and therefore could not kill him, as if there were

some lucky star that would always protect him. Of course, he knew that

was not true, and sometimes he would talk with her about how dangerous

it had become; but for a long time his luck was very good. My colleague

Richard Pyle once wrote of him that until the very end his run had been

so good that it was as if enemy gunners tracking a chopper had received

orders saying “Don’t shoot, that’s Larry Burrows out

there.” He

knew of course that he was not immune, that the risks were always there.

He told Vicky that the camera made him invisible, that the other side

could not see him and therefore could not kill him, as if there were

some lucky star that would always protect him. Of course, he knew that

was not true, and sometimes he would talk with her about how dangerous

it had become; but for a long time his luck was very good. My colleague

Richard Pyle once wrote of him that until the very end his run had been

so good that it was as if enemy gunners tracking a chopper had received

orders saying “Don’t shoot, that’s Larry Burrows out

there.”

Nine years of covering the war never made him cynical or hard or immune

to its cruelty. Quite the reverse. He seemed immensely sensitive to

the plight of the Vietnamese and the Americans alike. He worried about

the morality of what he was doing, photographing young men in their

moment of greatest anguish, and understanding always the terrible truth

that the greater the suffering, the better the photograph. When one

of his great photo essays, “One Ride with Yankee Papa 13,”

came out, he was very uneasy about showing such terrible tragedy with

such painful immediacy. He was greatly relieved when the mother of one

of the men killed in the operation wrote to tell him that his work had

helped her to understand the war, and that she was grateful for the

comfort she knew he had given her son in his final moments.

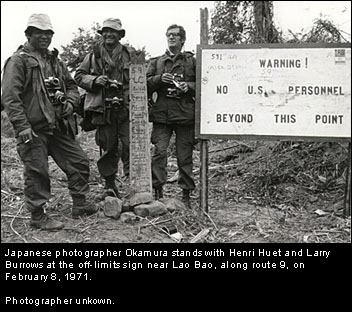

Larry

was not a very political man—his work is always beyond ideology

of any kind. It is distinguished by its humanity (a nonpartisan humanity).

It is unusually sensitive to the victims of war. If he had begun by

being something of a hawk, the endless stupidity and mindlessness of

the war had gradually made him politically neutral. He covered it for

nine years, from 1962 to 1971, watching the list of victims mount. In

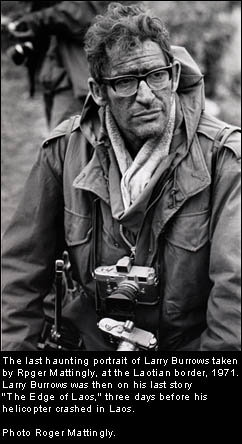

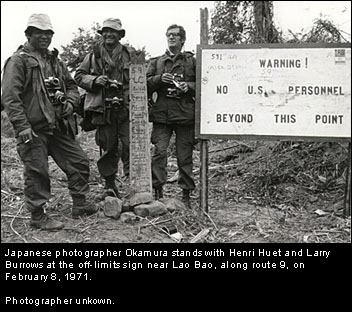

time he came to wear the pain of the war on his own face. In 1962 he

was young and boyish, oddly handsome. By 1971, the face had not so much

hardened as it had worn down, as if he had witnessed too much killing

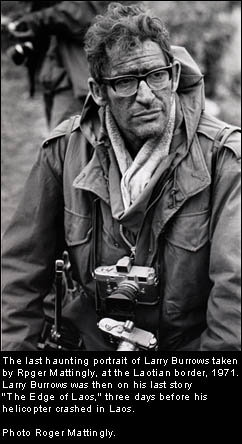

for too long. The last photo of him, taken by Roger Mattingly in February

1971, three days before Burrows was killed in Laos, is of a very different

man, fatigued, exhausted, his eyes behind those thick lenses tired and

fatalistic. He is only forty-four, but he is at that moment a very old

forty-four. Larry

was not a very political man—his work is always beyond ideology

of any kind. It is distinguished by its humanity (a nonpartisan humanity).

It is unusually sensitive to the victims of war. If he had begun by

being something of a hawk, the endless stupidity and mindlessness of

the war had gradually made him politically neutral. He covered it for

nine years, from 1962 to 1971, watching the list of victims mount. In

time he came to wear the pain of the war on his own face. In 1962 he

was young and boyish, oddly handsome. By 1971, the face had not so much

hardened as it had worn down, as if he had witnessed too much killing

for too long. The last photo of him, taken by Roger Mattingly in February

1971, three days before Burrows was killed in Laos, is of a very different

man, fatigued, exhausted, his eyes behind those thick lenses tired and

fatalistic. He is only forty-four, but he is at that moment a very old

forty-four.

After his death Ralph Graves saw that photo and said to Vicky, “Don’t

you just hate the picture of Larry looking so haggard?”

No, she had answered, she did not; she understood it and liked it. “I

never saw Larry looking like that,” Graves said. “Ralph,”

she answered, “you never saw Larry working.”

He was the most inventive of men, always tinkering with his equipment,

trying to make it better. He learned how to carry extra rolls of film

in his socks. He designed his own fatigue jacket, with extra pockets,

which suited his special needs, just as he designed an odd webbed structure

that allowed him, when crossing through waist-high paddy water with

five or six cameras, to lift all of them above the water level merely

by raising his left hand, and to lift his camera bag merely by raising

his right hand.

He was the most meticulous of men. If he had been out with other journalists

on an operation, when they all returned to the base camp the others

might rush to the bar to anesthetize their nerves. Meanwhile, Larry

would be back in the small room the military had assigned him, carefully

laying out all his equipment and cleaning every bit of it, checking

and polishing his lenses, taking them off the cameras so he could ventilate

the interiors. Then, even though his colleagues were almost surely still

in their fatigues (and three drinks ahead of him), he would dress for

dinner, in long-sleeved shirt and tie—“always the British

gentleman,” thought his slightly envious friend Faas.

He was the most meticulous of men. If he had been out with other journalists

on an operation, when they all returned to the base camp the others

might rush to the bar to anesthetize their nerves. Meanwhile, Larry

would be back in the small room the military had assigned him, carefully

laying out all his equipment and cleaning every bit of it, checking

and polishing his lenses, taking them off the cameras so he could ventilate

the interiors. Then, even though his colleagues were almost surely still

in their fatigues (and three drinks ahead of him), he would dress for

dinner, in long-sleeved shirt and tie—“always the British

gentleman,” thought his slightly envious friend Faas.

He was not entirely fearless. He was frightened of spiders and cockroaches,

and if he thought there was even the smallest spider in his bathroom

at home he would send Vicky ahead on an extermination mission. He was

afraid of heights; when he shot from certain high-rise buildings he

was terrified by the very idea, and he would explain to Vicky that he

had gotten through it by discipline—he simply refused to look

down. To the rest of us, of course, he seemed utterly fearless; we were

all too aware of the risks we were taking, that each mission we went

on changed the odds against us; and of course he had done it for so

long, and therefore the odds were even less favorable for him. But he

took those risks because they went with the territory; if you could

not accept them, you went home. Again and again his editors, worried

about his safety, would force him to take other assignments—the

British East India Company, the Taj Mahal, the birds of paradise—and

he would do them with his usual excellence, and then he would always

return to Vietnam. He longed, he told the editors, to photograph Vietnam

when the war was over, because the country was so beautiful.

I met him in 1962 in Saigon, when he was already a star. I thought then,

and I think now, that he was one of the most elegant men I ever met.

I have no memory of the stutter that others talk about. What I remember

of him are these three qualities: his grace, his modesty, and his generosity.

In those days, before the ascendancy of television and its star reporters,

the photographers for Life and Paris Match were the princes of the profession,

and many of them behaved exactly as such. Not Larry. He wore his own

supreme talent and professionalism lightly.

He treated young men like me, not yet established, with courtesy and

warmth. He seemed interested in what we thought, and he did not press

his opinions upon us heavily. He was a very good listener. Everything

he said was understated in a certain British way that is somewhat alien

to Americans. If there had been a hellish firefight and he had narrowly

escaped being hit, he might say that it had been “a bit dicey.”

My colleague Gavin Young, of the Observer, remembers coming back to

Saigon from one of the bloodiest battles of the war, and a young American

reporter asking what it had been like, and Larry answering, “Quite

lively in a way.” Then he had paused, and added, “You might

want to be a little bit careful.”

He knew he was very good at what he did, but he never let that knowledge

get in his way. I remember thinking that he was the kind of man I would

like to be when I grew up and that that was the way you were supposed

to do it—that if you were that good, people would know, and you

would not have to do the advertising yourself.

He was much loved by a vast number of colleagues, who greatly admired

the constancy of his work, the fact that he unfailingly caught the humanity

of the war in combatants and noncombatants alike. We admired him as

a man, because he kept photographing the war long after his own singular

reputation was set in concrete and it was time to go home and let someone

younger do it. He was determined to see the war through; he hoped someday

to shoot the coming of peace.

Larry Burrows died three months short of his forty-fifth birthday. I

write today thirty-one years after his death. He was mourned then both

by those who were his friends and by those who felt they knew him because

of his photographs, which brought so human a dimension to so cruel a

war. In retrospect, he was as much historian as photographer and artist.

Because of his work, generations born long after he died will be able

to witness and understand and feel the terrible events he recorded.

This book is his last testament.

© David Halberstam

David Halberstam is a legendary figure in American

journalism. His landmark trilogy of books on power in America, The Best

and the Brightest, The Powers That Be, and The Reckoning have helped

define the latter part of this century more than any journalistic works,

and have won him innumerable awards as well as broad critical acclaim.

David Halberstam graduated from Harvard, where he served as managing

editor of the daily Harvard Crimson. He began his career as the one

reporter on the Daily Times Leader in West Point Mississippi and later

at The Nashville Tennessean before joining The New York Times in 1960.

He first came to national prominence in the early sixties as part of

a small handful of American reporters who refused to accept the official

optimism about Vietnam and who reported that the war was being lost.

|

Vietnam at the moment of his arrival was not yet that big a story, though

it was soon to be the most important story in the world and to stay

that way for nearly a decade. The Americans were not yet in a combat

role and were still serving as advisers to the South Vietnamese Army,

or ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), as it was known. Larry Burrows

was pulled to it from the start; he understood that this struggle had

only begun, and that it was going to be, whatever the outcome, a bigger

war and a much bigger story than anyone back in New York realized. I

think he understood the unusually bitter quality of it because it was

a civil war; it is in the nature of civil wars to be especially cruel

and ugly. You can see the evidence of that in some of his very early

photos of Vietnamese tormenting Vietnamese. He also knew the one great

truth that the early generation of journalists and photographers who

went there understood: that given the particular nature of this war—small

units fighting all over the country—it was going to be, if you

figured out how to go and look for it, amazingly accessible for a photographer.

Vietnam at the moment of his arrival was not yet that big a story, though

it was soon to be the most important story in the world and to stay

that way for nearly a decade. The Americans were not yet in a combat

role and were still serving as advisers to the South Vietnamese Army,

or ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam), as it was known. Larry Burrows

was pulled to it from the start; he understood that this struggle had

only begun, and that it was going to be, whatever the outcome, a bigger

war and a much bigger story than anyone back in New York realized. I

think he understood the unusually bitter quality of it because it was

a civil war; it is in the nature of civil wars to be especially cruel

and ugly. You can see the evidence of that in some of his very early

photos of Vietnamese tormenting Vietnamese. He also knew the one great

truth that the early generation of journalists and photographers who

went there understood: that given the particular nature of this war—small

units fighting all over the country—it was going to be, if you

figured out how to go and look for it, amazingly accessible for a photographer.

What

he represented is historically important: the last great photographer

shooting an evolving war that was becoming more violent almost by the

day for a great and deeply influential magazine (which was week by week

and month by month becoming weaker and less influential). Even as he

worked, the importance of still photography was being muscled aside

by the coming of network television as the prime visual means of communication,

in what was the first television war, or in Michael Arlen’s apt

phrase, “the living-room war.” Larry arrived when reporters

and photographers were still part of what was called the press, and

not yet “the media.”

What

he represented is historically important: the last great photographer

shooting an evolving war that was becoming more violent almost by the

day for a great and deeply influential magazine (which was week by week

and month by month becoming weaker and less influential). Even as he

worked, the importance of still photography was being muscled aside

by the coming of network television as the prime visual means of communication,

in what was the first television war, or in Michael Arlen’s apt

phrase, “the living-room war.” Larry arrived when reporters

and photographers were still part of what was called the press, and

not yet “the media.”  He

knew of course that he was not immune, that the risks were always there.

He told Vicky that the camera made him invisible, that the other side

could not see him and therefore could not kill him, as if there were

some lucky star that would always protect him. Of course, he knew that

was not true, and sometimes he would talk with her about how dangerous

it had become; but for a long time his luck was very good. My colleague

Richard Pyle once wrote of him that until the very end his run had been

so good that it was as if enemy gunners tracking a chopper had received

orders saying “Don’t shoot, that’s Larry Burrows out

there.”

He

knew of course that he was not immune, that the risks were always there.

He told Vicky that the camera made him invisible, that the other side

could not see him and therefore could not kill him, as if there were

some lucky star that would always protect him. Of course, he knew that

was not true, and sometimes he would talk with her about how dangerous

it had become; but for a long time his luck was very good. My colleague

Richard Pyle once wrote of him that until the very end his run had been

so good that it was as if enemy gunners tracking a chopper had received

orders saying “Don’t shoot, that’s Larry Burrows out

there.”

He was the most meticulous of men. If he had been out with other journalists

on an operation, when they all returned to the base camp the others

might rush to the bar to anesthetize their nerves. Meanwhile, Larry

would be back in the small room the military had assigned him, carefully

laying out all his equipment and cleaning every bit of it, checking

and polishing his lenses, taking them off the cameras so he could ventilate

the interiors. Then, even though his colleagues were almost surely still

in their fatigues (and three drinks ahead of him), he would dress for

dinner, in long-sleeved shirt and tie—“always the British

gentleman,” thought his slightly envious friend Faas.

He was the most meticulous of men. If he had been out with other journalists

on an operation, when they all returned to the base camp the others

might rush to the bar to anesthetize their nerves. Meanwhile, Larry

would be back in the small room the military had assigned him, carefully

laying out all his equipment and cleaning every bit of it, checking

and polishing his lenses, taking them off the cameras so he could ventilate

the interiors. Then, even though his colleagues were almost surely still

in their fatigues (and three drinks ahead of him), he would dress for

dinner, in long-sleeved shirt and tie—“always the British

gentleman,” thought his slightly envious friend Faas.