"I hear there's a big operation up north." Larry said. I told him that was true, and gave him a brief rundown of what we knew: The South Vietnamese, with American air and logistical support, were preparing a massive cross-border attack into Laos, hoping to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail, Hanoi's supply line to southern battlefields. The operation - in some ways a repeat of the allied

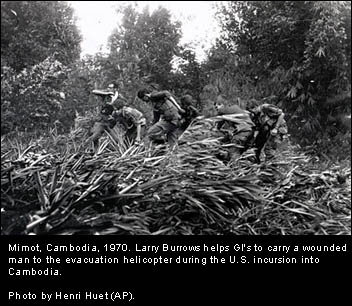

"incursion" into Cambodia the previous year - was anything but secret.

Indeed, while the press corps in Saigon remained subject to an official

"news embargo," the coming invasion was the subject of open speculation

in Washington and elsewhere. This was unprecedented for a Saigon press corps accustomed to nearly unfettered access to the battlefield in Vietnam. It also was unacceptable - especially for photographers like Larry, whose raison d'etre was getting close to the action. I don't remember his reaction, but it could not have been positive. When I returned to the AP bureau on the fourth floor

of the Eden Building, Burrows was discussing the situation with editors

in the photo department off the main newsroom. A few minutes later,

he left, with a grin and a final wave as he went out the door for what,

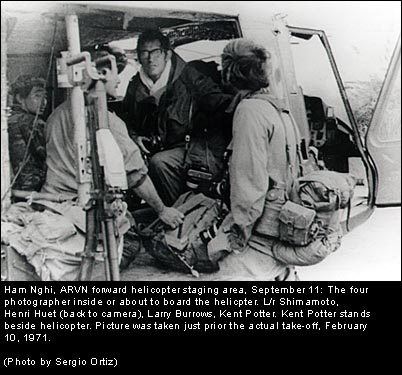

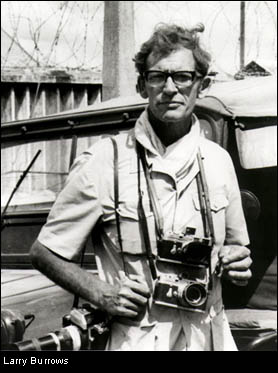

we could not know then, would be the last time. Straying over a heavily defended part of the Trail, their helicopter was shot down. Burrows, AP's Henri Huet, Kent Potter of UPI and Keisaburo Shimamoto, a Japanese freelancer shooting for Newsweek, were killed, along with the four-man crew, a South Vietnamese army photographer and two staff officers.  More than 70 accredited journalists perished or went missing in the Indochina war between 1965 and 1975, but few losses had the shattering effect of that crash. In Larry Burrows, we lost not only a friend and the best-known war photographer of his generation but a gentleman of uncommon grace, who at the peak of his profession always had time for newcomers and novices, and was generous toward even those few, like Henri Huet, whose skills and experience rivaled his own. Though pioneering television coverage made it the “living room war,'' Vietnam was where the still photograph had the greatest impact. It also was where a symbiosis between the print reporter and the photographer was most clear-cut; where each learned, if they didn't already know, the essentials of the other's trade. Reporters carried cameras; photographers took notes that served not only for captions but for stories under their bylines. For reporters and photographers alike there could be no better model, or more patient teacher, than Larry Burrows, who by presence, personality and professional demeanor was a natural mentor - a kind of father figure to younger journalists, which most of us were.

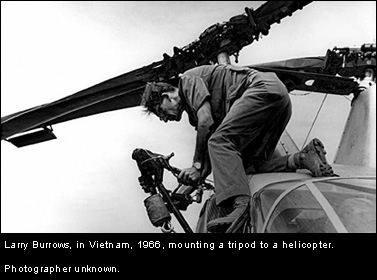

Larry also was a photographer of conscience, but rather than engage in the polemics and overheated rhetoric of some of his contemporaries, he let his camera lens speak to the human condition and the plight of the innocents caught in war. Though best known for Indochina, the London-born son of a British railway employee was far more than a war photographer, and in fact didn't like being identified as such. He reveled in photographing fine art, in museum and studio settings, and was as meticulous as they come - designing his own camera cases, planning assignments to the last detail, always renting a hotel room with two beds - one for himself and one to lay out his gear.

Among items found by a U.S. MIA search team that excavated the Laos crash site in March 1998, 27 years after the fact, were several pieces of 35-millimeter film, various lenses and the battered remnant of a Leica M3 - the only artifact with a serial number that could be traced. Company records showed it was bought in London on July 8, 1960. The purchaser was not listed, but Larry Burrows was the only one of the four who was in London at that time. Leica officials believe, as do we, that it is one of the cameras seen in many photographs of Burrows himself. It is the nearest thing to proof of identity that was found at the crash site. © Richard Pyle |

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

R

R

Caught

in rioting while covering the Congo's independence in July 1960, Burrows

suffered damage to his equipment and finished the job with a camera

cobbled together from parts. On return home, he would have needed new

gear, including the Leicas that were the favored tool of his trade.

Caught

in rioting while covering the Congo's independence in July 1960, Burrows

suffered damage to his equipment and finished the job with a camera

cobbled together from parts. On return home, he would have needed new

gear, including the Leicas that were the favored tool of his trade.