|

|

||||

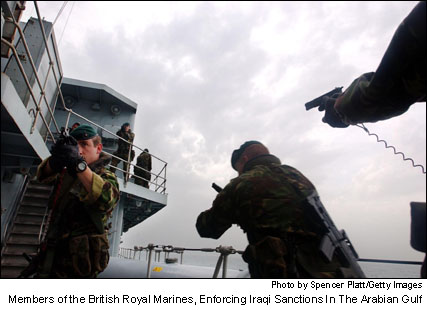

We are five miles off the coast of Iraq and the moon is full. Our vessel, a brawny Navy raft with a heavily armed U.S. Coast Guard law enforcement team aboard, rocks gently in the shallow opaque waters of the Arabian Gulf. I’m photographing the Military Interdiction Operations (MIO) and we’re waiting for the nightly ‘breakout” of dhows, a traditional Middle Eastern cargo vessel that has been plying these waters for centuries, and has been the backbone of a lucrative trade in embargoed merchandise both entering and leaving Iraq. On the eve of war with Iraq, these missions have taken on a particular importance as the U.S Navy is trying to secure the flow of traffic doing business with Saddam’s regime. With our anxiety heightened at the prospect of an encounter with one of the numerous Iraqi Navy boats that are in possession of these waters, we suddenly see something to our port side. “What’s that?” cries someone as three silhouettes emerge and then quickly submerge into the water. Silence overcomes our crew as we wait intently for the silhouettes to define themselves. Slowly, the silver backs of a school of dolphins break the waters surface, as if to quickly condemn the political games above before rejoining the quiet below. After a few relieved laughs we continue to wait for the dhows to break out and for the war to begin.

The Radisson Diplomat Hotel on the tiny archipelago Island of Bahrain, is where I, and hundreds of other reporters, photographers and television teams are calling home while waiting for something to materialize. The first sign that life in sleepy Manama, Bahrain’s lackluster capital, has been insidiously altered is found in the hotel’s ornate lobby where dozens of journalists are franticly surfing the web aided by the newly installed wireless connection. The installation of the WiFi connection, an idea that was probably conceived as a congenial tool to aid oil executives on their visits to Bahrain, has mutated into a kind of cyber newsroom where fistfights have been known to break out over the potential veto nations on the Security Council. It hasn’t helped matters that the area abuts a raucous nightclub that features a nightly leather-clad Philippino cover band.

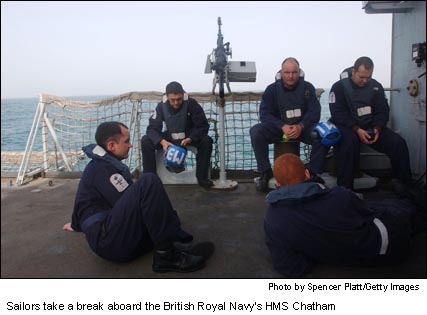

Being a visiting journalist on a ship is a painstaking lesson in Navy etiquette. Because of the confined living and work quarters, ships are a kind of condensed, floating city where any break with the equilibrium can have embarrassing and catastrophic effects. Embarked media are usually spared any pampering and are issued a bed, or “rack”, like any other seaman. Racks are stacked 3 high, leaving only about a foot of headroom between your bed and the next. For the dilettante, attempting to maneuver in this atmosphere is an exercise in advanced planning. Any rash move or superfluous act can agitate the 20 or so tired sailors that are within 10 feet of you. This will begin with some hushed grumbling and quickly advance from there.

Over the coming weeks the nature of our work here will likely change as many of us are embedded with military units and others join the caravan towards Baghdad. Maybe this will be the last war we actively wait for, maybe there will come a day when we wait with equal conviction for an international declaration of brotherly love. But for the time being there are chemical suits to buy, gas masks to try on and predictions to dispel. War is on the way and we need to be ready. Spencer Platt |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

The

access we’ve been given as journalists, while not unprecedented,

is impressive. We’re generally allowed to shoot and interview

whomever we want. While some ships are demanding that visiting journalists

have an escort with them at all times (more of a problem for writers

trying to conduct candid interviews), there is a sense that the military

is finally beginning to understand the needs of the media. When possible,

the navy has provided us with workspaces on the ships and email facilities.

So far there has been no cries of censoring of stories or images. This,

in itself, is a positive first step in this new-fangled liaison between

the press and the military.

The

access we’ve been given as journalists, while not unprecedented,

is impressive. We’re generally allowed to shoot and interview

whomever we want. While some ships are demanding that visiting journalists

have an escort with them at all times (more of a problem for writers

trying to conduct candid interviews), there is a sense that the military

is finally beginning to understand the needs of the media. When possible,

the navy has provided us with workspaces on the ships and email facilities.

So far there has been no cries of censoring of stories or images. This,

in itself, is a positive first step in this new-fangled liaison between

the press and the military.