| From a

Baghdad Balcony

'The Bombing Begins'

April 2003

by Seamus Conlan |

|

Photojournalist Seamus Conlan has been covering the

war in Iraq for People magazine and World Picture News, the photo agency

he launched in September 2001. Click here for more about WORLD

PICTURE NEWS.

4 p.m., 22 March, 2003

All

around me Baghdad burns. It looks like Saddam has lit the oil refineries

in and around the city. Huge black clouds of smoke circle the skyline,

blowing downwind, away from me. No, I wasn't hearing the sound of a

lone car as it came racing up, followed by a loud door slamming, followed

by the rumble of the shaking ground. Instead, the sound that I have

became accustomed to, over the last few days, is the distinctive clamor

of an air strike: racing car engine, distant door slam, cracking thunder

as the ground shakes. There. That was just another one, this time provoking

a little twitch in the neck at the very thought of it. Outside my balcony,

I can count 15 oil fires now burning around the city. All

around me Baghdad burns. It looks like Saddam has lit the oil refineries

in and around the city. Huge black clouds of smoke circle the skyline,

blowing downwind, away from me. No, I wasn't hearing the sound of a

lone car as it came racing up, followed by a loud door slamming, followed

by the rumble of the shaking ground. Instead, the sound that I have

became accustomed to, over the last few days, is the distinctive clamor

of an air strike: racing car engine, distant door slam, cracking thunder

as the ground shakes. There. That was just another one, this time provoking

a little twitch in the neck at the very thought of it. Outside my balcony,

I can count 15 oil fires now burning around the city.

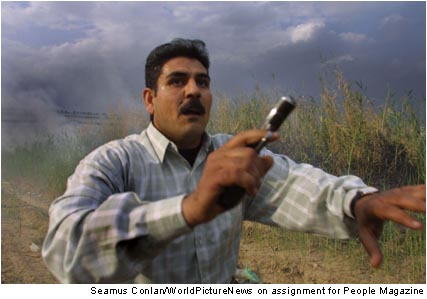

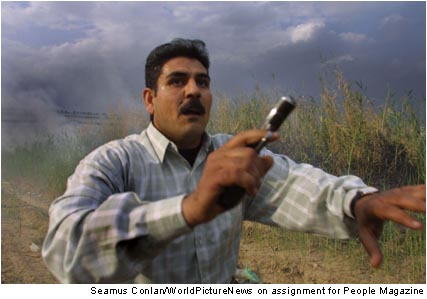

Inevitably, the next morning, comes faithful Sadune. "Do you want

to go to Critter? There were people hurt there. You must see for yourself,

Mr. Shams." "The press center was evacuated this morning.

We didn't think they would hit during the day."

He sighs, "Maybe we cancel it today. What you think? Too dangerous?"

Sadune, my minder or handler or whatever you call him, is a nice guy.

I wonder: When Saddam goes, will all these men shave off their moustaches,

the same way the men in Afghanistan shaved off their beards after the

fall of the Taliban?

Let me take a moment and think back a few days to the

week this war began. How did this all begin, this whirlwind of activity

and uneasy interludes, firepower and bloodshed, heightened senses and

raw emotion?

Just

before the Pentagon had given warning to all journalists to LEAVE IRAQ

IN THE NEXT 48 HOURS, more than half had already made their minds up.

"Have you heard?" "What if they take us as human shields?"

"What are you going to do if they come from room to room?"

"They might drag us out and shoot us." A few conversations

and a couple heart-to-hearts with friends at the bureaus back home,

and word begins to get around very quickly that doubt has set in among

the press pack. This is a hard-core group that I tend to see from one

conflict and country to another--an extended family, on the move, growing

over the years. You know the characters of these people quite quickly

in situations like this. Fear has spread among some of the commissioning

editors that have sent us out here. No one wants blood on their hands.

"They are sending me home." A few journalists clearly want

to leave but don't want to be the first to leave. A few scared individuals

are clearly spreading fear. "Are you leaving, are you leaving?"

How many times have I heard that in the last two hours? Just

before the Pentagon had given warning to all journalists to LEAVE IRAQ

IN THE NEXT 48 HOURS, more than half had already made their minds up.

"Have you heard?" "What if they take us as human shields?"

"What are you going to do if they come from room to room?"

"They might drag us out and shoot us." A few conversations

and a couple heart-to-hearts with friends at the bureaus back home,

and word begins to get around very quickly that doubt has set in among

the press pack. This is a hard-core group that I tend to see from one

conflict and country to another--an extended family, on the move, growing

over the years. You know the characters of these people quite quickly

in situations like this. Fear has spread among some of the commissioning

editors that have sent us out here. No one wants blood on their hands.

"They are sending me home." A few journalists clearly want

to leave but don't want to be the first to leave. A few scared individuals

are clearly spreading fear. "Are you leaving, are you leaving?"

How many times have I heard that in the last two hours?

In situations like this, many things run through your

mind quickly. Rumors spread like the oil fires outside my windows: They

will round us up and put us all back in the Al-Rasheed Hotel to use

us as human shields. The street fighting will be too dangerous to cover.

Chemical weapons are going to be unleashed. Such talk flies around the

press center. Fear will kill you, my mother always said. "Don't

you be frightened of nothing, young man," she would tell me as

a child. Over the last week that has been difficult.

The

next day, pullout is still the word. The Pentagon supposedly began ringing

the major networks and publications in the U.S. and, before long, the

roof of the ministry building that houses the press is being emptied.

A ghost town, apart from a few. Empty tents are left standing in the

wind that, only a few hours earlier, had been the live-feed point for

the networks. What is happening here? Is the U.S. government legitimately

concerned about our safety? Or is this exodus a function of the allied

commanders knowing that the press corps in Baghdad is on its own? We

are out of their control, unlike the embeds that are traveling with

them. We are free to express what we see and say. The

next day, pullout is still the word. The Pentagon supposedly began ringing

the major networks and publications in the U.S. and, before long, the

roof of the ministry building that houses the press is being emptied.

A ghost town, apart from a few. Empty tents are left standing in the

wind that, only a few hours earlier, had been the live-feed point for

the networks. What is happening here? Is the U.S. government legitimately

concerned about our safety? Or is this exodus a function of the allied

commanders knowing that the press corps in Baghdad is on its own? We

are out of their control, unlike the embeds that are traveling with

them. We are free to express what we see and say.

We get the order to pullout quickly; less than 48 hours

to go before the big storm rolls in. Pete Norman, my People colleague,

has no choice in the matter. He could lose his job. I, on the other

hand, am a freelance. Nonetheless, I have my wife, Tara, and our daughter,

Dylan, to think about. But also my career and what I feel is right.

With all the scare-mongering going around, it is a hard shot to call.

I know deep down that I came here to do a job and I haven't even begun

yet. How could I abandon the Iraqi people I've covered

off and on these past weeks and months? The women and children who live

here have nowhere else to go. So why should I? I would love to see Tara

& D. It hurts me to say, but I have to stay no matter what the outcome.

Pete

leaves at 5.00am. Jimmy (Nachtwey) awakens me to help fix his equipment.

I'd spent until after two in the morning loading drivers for his computer.

We all help one another as we can. The lament of many among us these

days: We're journalists. We all should have to do all of this. TV teams,

in contrast, come with military advisers, technicians, producers, dozens

of staff to pack up equipment. Photojournalists, instead, have to go

it alone. The digital age has not reduced the time-load saved by processing.

All it has done is create more work in those hours during which others

are waiting for our processed film. We shoot more since we don't have

to save on film now: 36 frames in the old days compared to 200 on a

flash card. We provide a bigger edit; more choice for the editors. But

what is the down side in a place like this? We now have ISDN sat phones

that transmit at a Meg a minute. (A year ago, in Afghanistan, it was

90 minutes a picture.) Even so, this requires extra flash cards, computers,

power supplies, batteries, generator, cables. More things to bring and

KNOW how it all works. If it goes down, then we need to be able to fix

it. Also, on top of the hard hat and vest, we now have three bags of

tech to bring. Not to mention the Bio-chemical suit. We look like a

film crew. When I checked into the hotel they asked me, "How many

rooms?" Pete

leaves at 5.00am. Jimmy (Nachtwey) awakens me to help fix his equipment.

I'd spent until after two in the morning loading drivers for his computer.

We all help one another as we can. The lament of many among us these

days: We're journalists. We all should have to do all of this. TV teams,

in contrast, come with military advisers, technicians, producers, dozens

of staff to pack up equipment. Photojournalists, instead, have to go

it alone. The digital age has not reduced the time-load saved by processing.

All it has done is create more work in those hours during which others

are waiting for our processed film. We shoot more since we don't have

to save on film now: 36 frames in the old days compared to 200 on a

flash card. We provide a bigger edit; more choice for the editors. But

what is the down side in a place like this? We now have ISDN sat phones

that transmit at a Meg a minute. (A year ago, in Afghanistan, it was

90 minutes a picture.) Even so, this requires extra flash cards, computers,

power supplies, batteries, generator, cables. More things to bring and

KNOW how it all works. If it goes down, then we need to be able to fix

it. Also, on top of the hard hat and vest, we now have three bags of

tech to bring. Not to mention the Bio-chemical suit. We look like a

film crew. When I checked into the hotel they asked me, "How many

rooms?"

Photographers Molly Bingham and Marco DiLauro bang

on my door. They have arrived on a tourist visa. How ? I've yet to find

out. Why, I wonder, were they given that ?

I speak with my wife Tara for 20 minutes and feel re-energized.

Love that woman.

Laying in a hot bath after a very long night and early

morning on the eve of the night of the first bombing, I turn my back

on everyone to get away from it all. Well, if today is possibly going

to be my last day, then I need to relax and enjoy it. After filing until

past 1.30 in the morning yesterday, I had a good drink and told myself

to sleep in. Now: a two-hour, hot, steaming bath, accompanied, unavoidably,

by dozens of bangs on the door. Knock knock..Heard the news, Knock..We

have to move back to the Al-Rasheed Hotel. Knock..No we don't. Only

the networks do. Knock..What are you doing if they bomb the hotel? "Am

going back in the bath. Close the door behind you." These people

are driving me crazy. The reason I wanted to relax was to get away from

all of this. It is going to happen today and who knows what it will

be like? Be safe and be alert. And so: Some good breakfast and loud

party music to chill me out and calm the soul. Crazy people driving

themselves mad, driving me mad. I was told in Rwanda: If we were sane,

we wouldn't be here. How very true. I really need to keep things together.

I'm sure I'm okay, it's just everyone else is going mad, not me. That's

my story and I'm sticking to it.

A

long night ahead of us, with the deadline running out at 4.00am local

time in Baghdad. Will the attack come at nightfall to give a good, hard

evening of raining terror? Maybe, but maybe not. With the deadline,

you can't really do that. We all wait in our rooms watching from the

balconies with baited breath. What will this be like? We've heard so

many stories now from the Americans, and from one another, that everyone

is wound up pretty tight, not knowing what to expect. Hour after hour

passes. Long--very long--stretches of not knowing. If you put fishing

poles in our hands, we would look like a fleet of fisherman on the riverbank,

not journalists waiting for a war. How do the people of Iraq feel if

we feel like this? We can go home, eventually, but this is their home,

a land awaiting its destiny. Is this going to be the war among wars,

the final hour? A

long night ahead of us, with the deadline running out at 4.00am local

time in Baghdad. Will the attack come at nightfall to give a good, hard

evening of raining terror? Maybe, but maybe not. With the deadline,

you can't really do that. We all wait in our rooms watching from the

balconies with baited breath. What will this be like? We've heard so

many stories now from the Americans, and from one another, that everyone

is wound up pretty tight, not knowing what to expect. Hour after hour

passes. Long--very long--stretches of not knowing. If you put fishing

poles in our hands, we would look like a fleet of fisherman on the riverbank,

not journalists waiting for a war. How do the people of Iraq feel if

we feel like this? We can go home, eventually, but this is their home,

a land awaiting its destiny. Is this going to be the war among wars,

the final hour?

It's midnight now and it begins

to sink in that it is getting late and maybe they won't

be coming tonight. A knock at the door, "I'll

take you with me on my bus at four or maybe five to see the sites after

the attack." "Do you think we will be able to go out tonight?"

" Oh yes, they will attack and we will see what they have done."

It appears that Sadune is thinking this is going to be like all the

other wars that Iraq has had in the last 20 years. Somehow I don't

share his optimism. "You come, we'll see."

I think he knows they will come on the deadline. I'll

wait till 1.00am to tune into the BBC World Service before going to

bed, just to hear what they say about all this craziness. "The

hours are closing in on Baghdad," comes the voice, crackling over

the radio. Only three hours left until 4.00am, the deadline set by George

W. Bush for this standoff to end peacefully. Oh, I'm

going to bed for a while.

At

4, I awaken instantly, still fully clothed. The World Service reports

that the deadline has passed. I sit and wait, peering into the sky,

watching small quick flickers off to 12 o'clock on the horizon. 5:22.

The ground shakes and tracer fire shoots up into the air over my balcony.

I can almost touch it. Baghdad is under attack. I hear the wail of my

first siren--a howl one doesn't hear while covering guerrilla warfare.

The sky is lit up and the echoing trails of tracers fill the night as

far as the eye can see. To the right, the left, I run through the hallway

and into the bedroom and look out the balcony. The sky is filled in

every direction. With this, loud cracks of gunfire. Turning around,

I go into the bedroom, and two loud thuds shake the building. I run

back to the living room to watch the oil refinery go up in smoke. I'm

slow and it's too dark to get a picture of it. But it will be the first

of many, and I feel a lot better for its having begun this way. I now

know what to expect. More strikes hit their targets as the sirens shout

out over Baghdad with a death cry. One two three four and maybe a fifth.

The military headquarters, just right of the oil refinery, is hit. Big

black clouds of smoke rise into the air. No flame; only a sound and

a shake. Nothing to worry about, I guess. This may be okay after all.

It turns out that informants in Saddam's inner circle had tipped off

the CIA, providing the exact whereabouts of Saddam on the first night's

strike. That, in fact, would have been extremely good luck had it all

played out with such fortunate, surgical precision. But no such luck.

The world would have said: Okay, one strike and he's out. But, no, the

game plays on, I'm afraid to say. Tracers continue to rain out over

Baghdad, through daybreak, until it's bright. At

4, I awaken instantly, still fully clothed. The World Service reports

that the deadline has passed. I sit and wait, peering into the sky,

watching small quick flickers off to 12 o'clock on the horizon. 5:22.

The ground shakes and tracer fire shoots up into the air over my balcony.

I can almost touch it. Baghdad is under attack. I hear the wail of my

first siren--a howl one doesn't hear while covering guerrilla warfare.

The sky is lit up and the echoing trails of tracers fill the night as

far as the eye can see. To the right, the left, I run through the hallway

and into the bedroom and look out the balcony. The sky is filled in

every direction. With this, loud cracks of gunfire. Turning around,

I go into the bedroom, and two loud thuds shake the building. I run

back to the living room to watch the oil refinery go up in smoke. I'm

slow and it's too dark to get a picture of it. But it will be the first

of many, and I feel a lot better for its having begun this way. I now

know what to expect. More strikes hit their targets as the sirens shout

out over Baghdad with a death cry. One two three four and maybe a fifth.

The military headquarters, just right of the oil refinery, is hit. Big

black clouds of smoke rise into the air. No flame; only a sound and

a shake. Nothing to worry about, I guess. This may be okay after all.

It turns out that informants in Saddam's inner circle had tipped off

the CIA, providing the exact whereabouts of Saddam on the first night's

strike. That, in fact, would have been extremely good luck had it all

played out with such fortunate, surgical precision. But no such luck.

The world would have said: Okay, one strike and he's out. But, no, the

game plays on, I'm afraid to say. Tracers continue to rain out over

Baghdad, through daybreak, until it's bright.

The following morning we are shown civilian wounded

in the hospital. These are not the victims of heavy shelling but people

who have literally been caught in the crossfire. Tracer bullets, shot

by Iraqi gunners, have landed on the Baghdad population. The casualties

we interview lived in areas too far away from one another, and their

wounds are too minor, to be accounted for by any other explanation.

Do these poor people really know that the allied forces want to liberate

them? I don't think so. They have had 12 years of

hardship and suppression from what they can only see as having come

at the hands of the Americans. I wonder what they will think or do when

the troops march on Baghdad.

Later that night the ministry building across the river

is hit with an almighty thud. Tracers continue to fill the sky. I'm

calm now, compared to the way I felt at this point the evening before.

I fire off a few frames before the flames go out. I think: Maybe the

lovely, friendly Iraqis might not be so friendly to us any more. This

will change things. I feel very guilty for being here and for what is

happening around me. I'm doing my job, showing the

world what is going on, not taking an active part. But somehow an entertainment

factor is running through my head. We are watching and letting this

happen. Strike after strike hit targets on the horizon. It is very dark,

and happening too quickly to really shoot anything. All I can do is

watch in disbelief, realizing that it has finally come to this.

After

gaining access to the roof of the hotel, through a broken door, I find

that I'm not the only one trying to get a bird's-eye view. But things

quiet down. We experience hour after hour of nothing, fishing poles

at the ready. Some photographers sleep on top of their equipment, laying

and waiting. Suddenly, the door to the roof swings open. Here come a

dozen or so men from the ministry. And one TV camera after another is

thrown to the ground. Photographer James Nachtwey's camera is taken

from him and thrown off the roof. A quick push and shove and a run for

it, scrambling to the stairs, before anything else happens. I ditch

the stairwell and hop on the lift at the 17th floor. As it descends,

I think: We can't mess things up now. We have a job to do. Stay out

of trouble, at least for a few days longer. A shame the roof will be

out of bounds now. That was a turning point: a ringside view or a backstage

pass to Baghdad. This is going to be trouble, I can see it. No sleeping

tonight. After

gaining access to the roof of the hotel, through a broken door, I find

that I'm not the only one trying to get a bird's-eye view. But things

quiet down. We experience hour after hour of nothing, fishing poles

at the ready. Some photographers sleep on top of their equipment, laying

and waiting. Suddenly, the door to the roof swings open. Here come a

dozen or so men from the ministry. And one TV camera after another is

thrown to the ground. Photographer James Nachtwey's camera is taken

from him and thrown off the roof. A quick push and shove and a run for

it, scrambling to the stairs, before anything else happens. I ditch

the stairwell and hop on the lift at the 17th floor. As it descends,

I think: We can't mess things up now. We have a job to do. Stay out

of trouble, at least for a few days longer. A shame the roof will be

out of bounds now. That was a turning point: a ringside view or a backstage

pass to Baghdad. This is going to be trouble, I can see it. No sleeping

tonight.

In fact, I do manage to catch a nap, only to be awakened

with an offer of a bus tour of the city--an attempt by Iraqi authorities

to show that all is well in Baghdad. I realize I can do without the

bus trip. Especially one on which you can't take pictures or get off

the bus. Especially with only an hour's sleep.

After

a visit to the Ministry of Information, we find directions to the hospital,

intending to see victims of the air strikes. Instead, we meet a brother

and sister who, sadly, tried to flee their home to seek refuge in a

nearby shelter, only to be hit by flying debris. He will be going home

today; she has abdominal injuries and must remain on the ward for awhile.

To my surprise, we see only a few other injuries. Again, it looks like

friendly fire from the not-so-friendly tracer bullets. After

a visit to the Ministry of Information, we find directions to the hospital,

intending to see victims of the air strikes. Instead, we meet a brother

and sister who, sadly, tried to flee their home to seek refuge in a

nearby shelter, only to be hit by flying debris. He will be going home

today; she has abdominal injuries and must remain on the ward for awhile.

To my surprise, we see only a few other injuries. Again, it looks like

friendly fire from the not-so-friendly tracer bullets.

Later, we find that there is no food in the hotel so

far today. Not even a cup of Turkish coffee, the local delight. "Hanid,

can you change a 20 to Iraqi Dinar?" "Quickly, Mr. Shams,

but be quick, ha? The B52's are coming in 15 minutes," he looks

white with fear. Hanid, working at the hotel reception desk, has asked

me, day after day, "Is it today? Should I bring my family here

now?" Rumors have been flying around, prompting photographers and

correspondents to get into position for the beginning of the big strikes.

The lift and the hallways are full of journalists trying to find a prime

position.

The chief targets, we all think, will be the main palaces

and, once more, the military headquarters building, on the far riverbank

of the Tigris, literally across from our windows. Only a week ago every

journalist stayed on that side of the river. But, one by one, we moved

to the "safe side," and took up residence in the Palestine

Hotel, abandoning our rooms at the Al-Rasheed. The Al-Rasheed, made

famous during the Gulf War in 1991, had more recently become known for

its military command center in the basement. Not the safest place in

Baghdad.

Just

on nine o'clock I hear a loud missile coming my way. It flies right

overhead in a screaming whistle. I run through to the bedroom balcony

to find the heavens opening with a thunder such as I have never heard

in my life. If I had been in the Al-Rasheed this instant, I would have

been blown to the other side of the room. For about a minute, the ground

shakes, continually, from the bombing that has sent hot flames of cloud

racing into the air. My first few exposures are shaky, the result of

the trembling building, and my attempts to catch my breath and get a

grip on what's going on. Focus. Get by, minute by minute. Deafening

thunder rains out only a few hundred yards away. Last night did not

prepare me for this. No flying debris, though, which is a good thing.

Tracers everywhere light up the sky as they hit, one after another,

along the riverbank. Just

on nine o'clock I hear a loud missile coming my way. It flies right

overhead in a screaming whistle. I run through to the bedroom balcony

to find the heavens opening with a thunder such as I have never heard

in my life. If I had been in the Al-Rasheed this instant, I would have

been blown to the other side of the room. For about a minute, the ground

shakes, continually, from the bombing that has sent hot flames of cloud

racing into the air. My first few exposures are shaky, the result of

the trembling building, and my attempts to catch my breath and get a

grip on what's going on. Focus. Get by, minute by minute. Deafening

thunder rains out only a few hundred yards away. Last night did not

prepare me for this. No flying debris, though, which is a good thing.

Tracers everywhere light up the sky as they hit, one after another,

along the riverbank.

I race up to a colleague's room,

which affords a better view. The thunder again, a bit too close for

comfort. My stunned and mixed emotions are sickening. It isn't

easy to witness and record attacks of aggression for a living. Maybe

in my misspent youth I might have had a different approach to life and

enjoyed the fireworks. But this has been a display of unleashed terror,

the likes of which I didn't think existed. The hand

of God couldn't have done it any more effectively.

After that night of heavy air strikes teeming down

on Baghdad, it doesn't worry me anymore. Now I know

why the Iraqis are still driving their cars outside my window even as

the shells are landing every half hour. This is the way it is. We keep

on. We do what we have to do. There is no siren anymore, no call for

the "all clear" sounded today. And no tracers light up the

sky anymore. These were so ineffective, why bother? The shells continue

to land but now we can only hear them, not feel them. Their intended

targets are too distant.

But, not to worry, they will come again. And soon.

© Seamus Conlan

seamusconlan@worldpicturenews.com

Part II:

'Molly's

Missing'

|