Constant danger, without the soldier’s glory, is the burden of photographers and correspondents in the field during times of war. From the American Civil War in the 1860’s to the current war with Iraq, American photographers and journalists encountered dangers as they introduced innovative changes and generated controversy. In addition to exposure from hostile fire, correspondents weathered other storms. Conflicts between members of the press and the military occurred as frequently as desert dust storms. Criticism rained down from the government and the public over the quality of coverage. Yet in spite of the criticism, the American public expressed more interest and demanded more information. And with this increased demand, journalists and news outlets were forced to utilize new communications technologies to provide more information and visual images. Today, people around the world watch the current conflict as if they are riding alongside the troops. The American Civil War serves as a basis for modern warfare reporting and represents the dawn of the age of providing news for the masses about armed conflicts. The American Civil War serves as a prime example of the increased demand for wartime coverage and utilization of new technology by the press that endures to the present day. The Civil War involved Americans from all walks of life – white and black, rich and poor, new immigrants and established citizens. The conflict consumed the nation for four bloody years. And just as the Iraq War today created new audiences with its around the clock reports, the Civil War opened new doors for journalists and the print media. The American Civil War set standards for immediate and complete coverage that extended into the next century and to the twenty first-century war in the Middle East. With the opening shots of the American Civil War at Fort Sumter, South Carolina on April 12, 1861, coverage of major battles and small skirmishes appeared in the nation’s newspapers. The telegraph allowed for rapid transmission of stories to the urban news centers. Visual images became available from commercial photographers. The government and the military, in the North and the South, attempted to control this coverage in a variety of ways. Battlefield reporters faced censorship, intimidation, official delays and any number of restraints. But resourceful photographers and journalists found a way to get their images and stories through to a public starved for news about the war.

Families created a great demand for individual portraits. Photographers met these requests and also extended their efforts to the battlefields. They provided graphic images of the true nature of the civil war. Pictures from the front lines showed bloated corpses, skeletal remains and severed limbs. Burned buildings and landscapes scarred from fighting emerged into public view. Starving prisoners, newly freed African American slaves, and boy soldiers appeared as a graphic illustration of the war. Americans and people around the world never witnessed anything like this before. War photography began in the 1840’s, but the Civil War created an explosion of coverage. By the 1860’s, photographs provided a complete representation of the war. The mass distribution of photographs provided vivid evidence of the desperate nature of the conflict.

Mathew Brady did not actually shoot many of the Civil War photographs attributed to him. He primarily supervised his photographers and purchased others from battlefield photographers to expand the coverage. Brady's best-known photographers included Timothy O'Sullivan and Alexander Gardner. As one of Brady’s biographers noted, “when photographs from his collection were published, whether printed by Brady or adapted as engravings in publications, they were credited ‘Photograph by Brady,’ although they were actually the work of many people.” Brady’s actions led to considerable animosity from other photographers.

As Brady and other photographers captured the visual carnage of the war, a number of journalists brought their literary talents to the battlefield. One of the best known Civil War correspondents, Charles Anderson Page, covered the Civil War for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. In his first report of a battle, Page witnessed a horse gallop right past him. All that remained of the rider was his booted leg – still in the stirrup. Page wrote of the incident: “During the stampede, for a moment the attention of hundreds was attracted to a horse galloping around carrying a man’s leg in the stirrup – the left leg, booted and spurred. It was a splendid horse, gaily caparisoned.” The managing editor of the Tribune described his correspondent stating “Page shows a nice eye for the grotesque.” Born in 1838, Page grew up in Illinois, worked for the Mount Vernon Iowa News and became a staunch supporter of Lincoln. With Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 presidential election, grateful Republicans provided Page with a job in the Treasury Department. He went to the Tribune in 1862. Horace Greeley awarded him the privilege of a byline because of the popularity of his reporting, a rarity for reporters in this age. “C.A.P., our special correspondent,” headed Page’s stories. Page earned commendations from his editors for his descriptive writing, his ability to understand soldiers and military operations, his sense of humor and his persistence. He wrote in a popular style as if recording events in a diary for his readers. Page covered the Union Army from 1862 until the war’s end in 1865. He chartered boats and trains and freely spent the newspaper’s money – all expenses for obtaining his stories. Greeley at one point complained to Page that he was “the most expensive young man the Tribune has ever employed.” Page responded “Early news is expensive news, Mr. Greeley; if I have the watermelons and whiskey ready when the officers come along from the fight, I get the news without asking questions.” Greeley tolerated the inflated costs because of the reliability and punctuality of Page’s stories. Apparently, the watermelon and whiskey loosened the tongue of many officers and regular soldiers. At the war’s conclusion, Page became one of the first correspondents to enter Richmond following its occupation by Grant’s army in April 1865. Page wrote of the calamities and dangers he and other journalists faced during the war. Mr. Winser of “the Times” had his horse shot under him at Cold Harbor, Virginia. Mr. Anderson of “The Herald” was hit in the arm at Wilderness. Richardson and Browne of “The Tribune” spent sixteen months in Rebel prisons. All have had their “hairbreadth ‘scapes,” Page stated. Page and other journalists, both north and south, received a barrage of criticism for their stories. With the competition for coverage among newspapers and magazines, many publications rushed stories into print which later proved to be erroneous or misleading. Critics accused many northern newspapers of treason for providing military information to the south. The military warned editors that their papers would be punished for providing “unauthorized” news. The War Department threatened newspapers with the loss of the telegraph lines. Generals also retaliated against reporters. Union General William T. Sherman arrested Thomas W. Knox of the New York Herald for providing information to the enemy and threatened to hang him. Knox lived but never covered Sherman’s army again. All of the threats and censorship failed to stem the swelling tide of war news in the pages of the newspapers. The issues of new technology, expanded coverage,

government restrictions and national security began with the Civil War.

And while the times and techniques have certainly changed since the

1860’s, the fundamental issues remain for wartime coverage to

this day. © Patrick L. Cox,

Ph.D.

|

||

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

The

Civil War became the first major conflict with extensive photographic

coverage. Matthew Brady became the most famous Civil War photographer,

but hundreds of others covered the battles, campgrounds, devastated

cities and the impact of the war. In the South, George S. Cook of Charleston

captured scenes from the war that began with Major Robert Anderson’s

surrender of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces. Photographs would not

appear in newspapers and magazines until the next generation. But the

photos of Brady, Cook and others served as the basis for illustrations

that appeared in the print media throughout the Civil War. From this

time forward, all military conflicts would have illustrations and graphic

art as a standard part of the coverage. Because of the massive numbers

of people involved in the conflict, a tremendous demand for these images

stimulated the efforts of these commercial photographers to extend their

coverage into all areas of the nation.

The

Civil War became the first major conflict with extensive photographic

coverage. Matthew Brady became the most famous Civil War photographer,

but hundreds of others covered the battles, campgrounds, devastated

cities and the impact of the war. In the South, George S. Cook of Charleston

captured scenes from the war that began with Major Robert Anderson’s

surrender of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces. Photographs would not

appear in newspapers and magazines until the next generation. But the

photos of Brady, Cook and others served as the basis for illustrations

that appeared in the print media throughout the Civil War. From this

time forward, all military conflicts would have illustrations and graphic

art as a standard part of the coverage. Because of the massive numbers

of people involved in the conflict, a tremendous demand for these images

stimulated the efforts of these commercial photographers to extend their

coverage into all areas of the nation. At

the start of the Civil War, Matthew Brady owned fashionable portrait

studios in both New York and Washington. Once the shooting began, Brady

sent his Washington photographers directly to the field of battle. Later,

both Brady and his partner Alexander Gardner claimed credit for the

wartime photographs. Professional photographers followed Union and Confederate

armies, although most concentrated on individual portraits of soldiers

to send home to their families. But Brady wanted to document the war

on a grand scale and he employed many photographers to follow the troops

in the field. Brady saw action himself, continuing to photograph even

after his wagon came under fire at Bull Run. Years later, Brady commented,

"I had to go. A spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went."

At

the start of the Civil War, Matthew Brady owned fashionable portrait

studios in both New York and Washington. Once the shooting began, Brady

sent his Washington photographers directly to the field of battle. Later,

both Brady and his partner Alexander Gardner claimed credit for the

wartime photographs. Professional photographers followed Union and Confederate

armies, although most concentrated on individual portraits of soldiers

to send home to their families. But Brady wanted to document the war

on a grand scale and he employed many photographers to follow the troops

in the field. Brady saw action himself, continuing to photograph even

after his wagon came under fire at Bull Run. Years later, Brady commented,

"I had to go. A spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went."

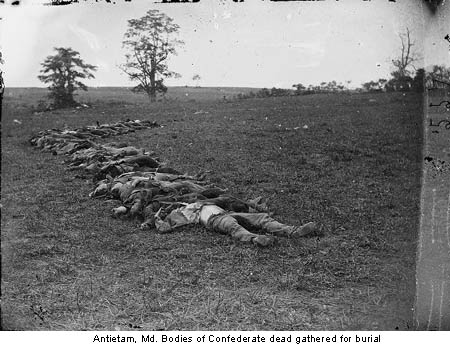

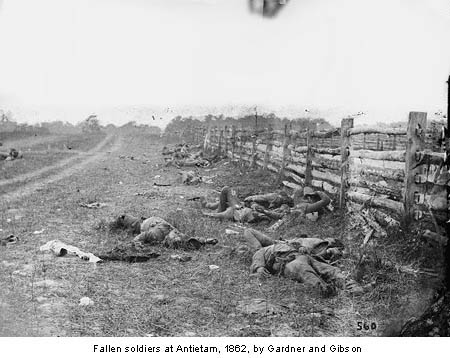

Brady

shocked Americans with his photographs of battlefield corpses after

the battle of Antietam, the deadliest single day of the entire war.

He displayed a sign on the door of his New York gallery that read, "The

Dead of Antietam." The 6,000 dead and 17,000 wounded from the September

17, 1862 battle numbered four times the total casualties suffered by

Americans at the Normandy invasion in June 1944. By 1862, casualty lists

became a standard front-page feature in northern and southern newspapers.

Brady’s dramatic photographs marked the first time most people

witnessed the widespread death and suffering of the war. The New York

Times said that Brady brought "home to us the terrible reality

and earnestness of war." Brady received criticism in the press

and from the government for the graphic nature of some of his work.

But he continued his labor at the battlefront until the final days of

the Civil War.

Brady

shocked Americans with his photographs of battlefield corpses after

the battle of Antietam, the deadliest single day of the entire war.

He displayed a sign on the door of his New York gallery that read, "The

Dead of Antietam." The 6,000 dead and 17,000 wounded from the September

17, 1862 battle numbered four times the total casualties suffered by

Americans at the Normandy invasion in June 1944. By 1862, casualty lists

became a standard front-page feature in northern and southern newspapers.

Brady’s dramatic photographs marked the first time most people

witnessed the widespread death and suffering of the war. The New York

Times said that Brady brought "home to us the terrible reality

and earnestness of war." Brady received criticism in the press

and from the government for the graphic nature of some of his work.

But he continued his labor at the battlefront until the final days of

the Civil War.