|

Inside Television's First War

April 2003

by Ron Steinman |

|

Excerpted from Inside Television's First War: A

Saigon Journal by Ron Steinman, published by the University of Missouri

Press in 2002. For further information, please call (800) 828-1894.

Now that the war in Iraq is in full swing, it is time to reflect

on how broadcast journalist covered the Vietnam War, now so distant,

yet still the war because of all its problems that dominates our thoughts

even in this, the early part of the Twenty First century.

Today

high tech dominates our lives, including journalism. One thing remains

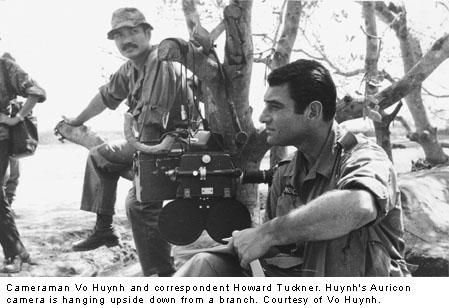

though, the ability, integrity and talent of the reporters, whether

working a video camera, or a still camera. In Vietnam our large and

heavy cameras for television used film. Their profile Today

high tech dominates our lives, including journalism. One thing remains

though, the ability, integrity and talent of the reporters, whether

working a video camera, or a still camera. In Vietnam our large and

heavy cameras for television used film. Their profile

often made them look like rocket launchers, In Vietnam there were no

computers. No equipment had microchips. Cell phones did not exist. Portable

video tape was a gleam in someone's eye. Lipstick cameras and video

phones were the stuff of science fiction. Digital was but a dream. Satellites

only came with regularity during the Tet Offensive in January 1968.

Today portable satellite dishes fit easily into a small suitcase. We

transmitted nothing live. This may seem hard to believe, but we never

fed anything from the battlefield and never anything from Vietnam. In

this war, live transmissions are normal and if not live, journalists

send material soon after they record it, sometimes after they've edited

it. How long would the Vietnam War havelasted had we that capability?

I'd wager it would have ended years earlier because the public would

have said enough. We now have remarkable equipment for getting the story

and each day it gets better. The pressures are greater because now there

are many networks, local stations on the scene, radio stations, newspapers

everywhere, more magazines than one can count and the insatiable Internet.

The demand for immediacy is overwhelming. War was different in Vietnam.

Our attitude toward war and how we covered it, was also different. We,

that is the press and the military, our military and our biggest adversary,

were in it for the long haul. We, as I describe below, went anywhere

we wanted, and covered just about everything we wanted. That made all

the difference in our coverage and what we presented to our audience.

The following is a look how we in one bureau, NBC News, covered the

war.

I became the Saigon bureau chief for NBC News in April 1966 and servedfor

twenty-seven months until July 1968, thus becoming a part of the history

of the war in Vietnam. The reports generatedb y my bureau andall the

other news bureaus, broadcasters, wire services, magazines, and newspapers

defined the war then andfor generations of Americans to come. We didnot

know the effect the war wouldha ve on the future when we coveredit.

I became the Saigon bureau chief for NBC News in April 1966 and servedfor

twenty-seven months until July 1968, thus becoming a part of the history

of the war in Vietnam. The reports generatedb y my bureau andall the

other news bureaus, broadcasters, wire services, magazines, and newspapers

defined the war then andfor generations of Americans to come. We didnot

know the effect the war wouldha ve on the future when we coveredit.

Covering the war in Vietnam was hugely different

from the way we cover any story today, especially a war. We found our

story in the field, in jungles, in rice paddies, and along the beaches

and mountain ranges where we knew we could fill the screen with American

soldiers in trying situations. The story moved too fast for an outside

entity to run our operation. We had to move quickly, without waiting

for the assignment desk in New York to say “go.” We decided

what to cover because we were the ones on the ground and we knew the

story better than anyone, especially someone in a dry, well-lit office

thousands of miles away. To our advantage, communications with headquarters

were terrible, which meant less interference. Today, network headquarters

usually has control over coverage of events. Communications by satellite,

computer, and telephone are far superior and bureau chiefs in distant

places have less authority. Getting on the air live and first often

takes priority over good journalism, a major problem of broadcast news

today. We participated in a way of life and away of journalism during

those busy years that none of us will ever see again. It is sad to think

that most journalists today will never know the sustained high, the

rush, that accompanies reporting under such intense, let-it-all-fly

conditions.

Until the mid–nineteenth century, the modern war correspondent

did not exist. When one of the London papers wanted to report a war,

it arranged to have military officers or English nationals who were

in the fight or observing the action—amateurs to journalism—write

letters to the paper. These letters had the wonder of the new about

them but were long and rambling, dominated by detail that only those

with great patience could endure to read. These dispatches were journalism

of a sort, but nothing like what would come. When the Times of London

hired William Howard R ussell to cover the Crimean War (1853–1856),

reporting on war changed forever. Though Russell and his fellow full-time

reporters showed great courage in reporting from the front lines, technically

they had to know only how to put their pen to paper and get their stories

on the next fast packet to Great Britain, no small feat.

In Vietnam, television correspondents had to know much more about their

craft, because it had become far more complicated. By the time reporters

went to war, the overt trappings of their craft had be ome second nature.

After all, most were children of television and, as such, had an unconscious,

though learned, understanding of the medium. They knew how to stand,

how to sit, how to hold a microphone, and how to conduct an interview

for the camera. They knew how to “write to picture,” how

many words per second to speak, and how to do the “stand-up”:

how to look like you’re not in danger though you are and, conversely,

how to look like you are in danger when you are not. If a correspondent

lacked these basic skills, his reports would be weak, his composure

unsteady, his ability to talk to his audience a failure. Fortunately,

though such reporters existed, they were in the minority.

But few reporters who arrived in Vietnam had the training it took to

be a war correspondent. Covering war is nothing like covering the local

gardening club or the progress of a bill through the House or Senate.

Unfortunately, news agencies did not have the money and staff to afford

the luxury of sending only those experienced in war to cover war. Vietnam

was the first major American groundwar since Korea and few , if any,

of the broadcast journalists who covered Korea later made their way

to Southeast Asia. NBC News recruited young reporters, many of whom

were working at local stations, the farm system for the networks. Eager

to succeed but anxious about falling bombs and flying bullets, most

did well. Boot camps for war correspondents did not exist. Would they

have worked? No. Only experience can teach journalists how to report

on war. We had veteran reporters such as Wilson Hall, Dean Brelis, and

Paul Cunningham along side the novices and I would like to think they

sometimes led y example. But training by doing prevailed. Good journalists

learn to parachute with little notice into the unknown. By virtue of

tenacity, guts, skill, training, and intelligence—and often with

the help of an apt local guide—they manage surprisingly well at

the start of their tour to survive, then grow wings and fly .

Journalists who cover military issues can find

themselves spending too much time trying to understand budgets. They

concern themselves with investigating cost overruns, soldiers’

pay and housing , and weapons systems. All are valid and worthy pursuits.

Their best education in war, however, is under fire. Exposure to danger

matters more than what anyone can learn in the classroom. Textbooks

provide templates for proper procedure: the who, why, what, and where

of the story. But the doing—that is, the coverage itself—becomes

so compelling, and often overpowering, that instinct rules rather than

learned lessons. My reporters had varying strengths and levels of commitment

to their craft. Some learned their trade faster than others. Some, however,

never learned the skills to successfully operate in a war zone like

Vietnam, with its ever-shifting, unstable fronts, its ambushes and frequent

terror.

Journalists who cover military issues can find

themselves spending too much time trying to understand budgets. They

concern themselves with investigating cost overruns, soldiers’

pay and housing , and weapons systems. All are valid and worthy pursuits.

Their best education in war, however, is under fire. Exposure to danger

matters more than what anyone can learn in the classroom. Textbooks

provide templates for proper procedure: the who, why, what, and where

of the story. But the doing—that is, the coverage itself—becomes

so compelling, and often overpowering, that instinct rules rather than

learned lessons. My reporters had varying strengths and levels of commitment

to their craft. Some learned their trade faster than others. Some, however,

never learned the skills to successfully operate in a war zone like

Vietnam, with its ever-shifting, unstable fronts, its ambushes and frequent

terror.

Though some of the reporters who worked for me had servedin the army

or marines and several had covered other wars, most had no previous

military experience. They all tried, though, and the lack of a full

understanding of the military mind and its often arcane culture rarely

got in the way of doing a good job . In the thousands of television

stories and radio reports that we sent from the bureau to the American

people, there were few mistakes of substance, though military purists

might disagree. We learned to treat the military with respect and never

to assume that anyone wearing a uniform was one-dimensional. We understood

they could think for themselves when orders from higher-ups superseded

good sense.

While many of us knew next to nothing about the military, its customs

and culture, none of us knew anything about the Vietnamese people, their

customs and culture. But we had to learn everything we could, and fast,

to survive. I found ignorance of Vietnamese values and customs to be

shockingly high among senior officers. Perhaps I expected too much,

as these men only reflected the policy from Washington, and our legislators

and the executive branch proved equally delinquent. The U.S. command

dismissed the enemy’s goals as either simplistic or naive, rarely

understanding that they believed truth was on their side. This made

it a strange war by any yardstick.

We did not always believe what we heard from people in the government,

whether in or out of uniform. They had an agenda and we did not. They

had orders and we had curiosity. Many of us found it difficult to believe

everything they said or, sometimes, preached. It resulted in a constant

tug of war between truth and propaganda when we dealt with government

officials. The situation in Vietnam demanded continuous intellectual

pushing and shoving if we were to get the story we knew existed. Covering

the whole war, we sometimes knew more about a story than an officer

confined to a specific tactical zone. We were not always correct in

our conclusions, but we tried mightily to get to the truth. The military

thought, as do professionals in any business, that we journalists could

never understand their work, especially when it involved danger. However,

once you’re under fire from shelling or small arms, or witnessing

a terrorist attack, that old saw dies quickly.

So how do you learn to cover war? In some ways, you never do. But you

learn by doing, by asking many questions, and by coming to grips with

fear. Knowing that fear is real often provides enough protective covering

when the unexpected takes place, which it always does. To survive, you

learn when to duck and how to identify the whistling sound of mortars

and the angry belch of a 105-mm howitzer. You learn to distinguish the

crack of a Viet Cong AK-47 from the pop of a Chinese recoilless rifle

and the friendly soundof an M-16. You learn to cross your fingers and

to wear, if available, a steel helmet on your head and a flak jacket

to protect your chest, heart, and back. Helicopter pilots routinely

lined the floor of their thin-shelled air craft with flak jackets. More

than once, enemy rounds struck and pierced the floor of a helicopter

in which I was a passenger. Fortunately, though the “bird”

bucked from the impact, the rounds never made it any closer to those

of us inside because of those extra jackets.

Even when there is no combat and no shots sound, there is little theorizing.

Lessons for the future are rarely considered. Our bar talk concerned

our lack of sleep, our horrible living conditions, the heat, the monsoon

rains, the bad food, and the terrible wine. We may have swapped stories,

but rarely did we discuss specifically how to cover the war. Reporters

talked about how misunderstood they were by producers and editors at

home, and how they missed their loved ones. They talked about their

next drink, their last meal, and occasionally about women. They did

not think of journalism as anything other than a way of life, one that

they wouldn’t substitute for anything. I believed then that, more

than the skills needed to cover the war, instinct honed by experience

would guide the reporter through most, if not all, situations. I still

hold that belief as gospel. To succeed in covering any war—especially

a story as diverse as Vietnam, with its many images, in pictures and

words, giving the look of a splintered windshield—it’s important

to be active first and to intellectualize second.

But covering war is more than seeing and experiencing action. There

is the culture, the history, the food, the climate. By learning how

the local people live, you become a better reporter and help yourself

to avoid injury or, worse, death. At least, that is the hope. It can

also help you make sense of the mystery surrounding the story you are

covering. Vietnam remained ever enigmatic. There were too many areas

where meaning stayed unclear, motives vague, and goals clouded. The

goal of the correspondent and the all-important cameraman—and,

through them, my goal as well—was to clarify the puzzle, if possible,

and dig through the morass without violating the principles of the trade.

Once the story was complete, it was up to the gatekeepers at the various

stages of production to ask the right questions in the quest for accuracy.

The public expects reporters to cover everything that happens—that

is, all the stories we can find. But in war, many stories may have obscure

origins and be difficult to explain. Today, many who hold top management

positions at the media conglomerates also expect journalists to entertain

as they inform. Fortunately, that attitude played hardly any role in

the Vietnam era. Doubtless, much of what we reported from Vietnam influenced

our audience: people at home and in government, the military, foreign

allies, and our enemies. In the late 1960s and in the 1970s, communications

was still in its infancy as far as speed was concerned, and events with

new twists sometimes overshadowed the events documented in our pieces.

Yet, our stories remained valid and usually had enough heart to receive

substantial airplay because they explained the reasons behind the events.

Though the networks covered the war in the early 1960s, it took a backseat

to other news, as if the press lords did not have the time, energy,

or perhaps the stomach to focus on the war full-time. In Vietnam the

buildup was slow, almost ignored until late 1965 when the number of

American troops started edging into the hundreds of thousands, culminating

in more than half a million by early 1966. Until the emergence of CNN

in the 1980s, there were fewer channels demanding fresh news. News did

not command the air twenty-four hours a day; news broadcasts had fixed

times. Fixed schedules made for “appointment television.”

Viewers knew they could see morning television starting at 7:00 a.m.

The network evening newscasts were on at either 6:30 or 7:00. Listeners

could find radio newscasts every hour throughout the day. Breaking news,

if warranted, came into the home at odd times, but these stories were

always special. We never broadcast anything frivolous, because we wanted

the audience to know they could trust us to give them what we considered

important. The television news business in that era had different motives,

and I like to think we were better, more focused, less tabloid.

There

were only three television networks, but we were not any less competitive.

I knew our competition, their strengths and weaknesses, and I sometimes

covered stories with that in mind. If CBS had a weak correspondent on

a particular military action, I might try, if I had one available, to

put a stronger team in the field. Rarely were we head to head covering

the same squad or even platoon. Thousands of men were fighting or hunting

for the enemy, but for us, most of the action took place on a very small

scale. This allowed us to cover stories, or parts of them, where we

were alone, the competition not in sight. Perhaps we were even exclusive

(a much overused term) to an entire battle. There

were only three television networks, but we were not any less competitive.

I knew our competition, their strengths and weaknesses, and I sometimes

covered stories with that in mind. If CBS had a weak correspondent on

a particular military action, I might try, if I had one available, to

put a stronger team in the field. Rarely were we head to head covering

the same squad or even platoon. Thousands of men were fighting or hunting

for the enemy, but for us, most of the action took place on a very small

scale. This allowed us to cover stories, or parts of them, where we

were alone, the competition not in sight. Perhaps we were even exclusive

(a much overused term) to an entire battle.

We hopedthat what we covered served a larger purpose than simply attracting

and holding an audience. On the other hand, we were never so naive as

to assume we could do without the audience, so we didn’t tone

down our coverage or ignore the obvious. Combat, the battle itself,

action, is what is obvious in war and the easiest story to cover. But

when we covered combat just for the sake of combat, it served only to

stir the prurient in us. It edged easily toward pornography. Showing

only combat is a poor substitute for covering other news in a war zone

(though there is nothing more serious than death). It limits the growth

of the correspondent and his crew, and is thus a disservice to the audience.

In the end, the audience appreciates that there is little difference

from one combat story to another except the nature of the horror. Of

course, battle footage, with guns firing and men wounded and killed,

did serve a purpose. The people sitting safely and snugly at home had

the opportunity to see the ultimate, inherent futility of the war.

There is a continuing debate about the so-called moral detachment of

the journalist,

especially in war, where destruction and violence prevail. Is there

a right and wrong here? How much should journalists be involved in the

stories they tell? Does the choice of a sound bite and pictures, and

the placement of those pictures against the narration, unduly influence

the direction the story takes? When a reporter gives too much thought

to the morals and ethics of the storytelling, the result can reek from

the personal rather than be naturally strong from its inherent value.

We must never underestimate the audience’s ability to recognize

feigned or imposed morality. Such imposition can bring a story from

the potentially airy height of pure reportage down to the muddy waters

of personal involvement. There are those who believe reporters can and

should show moral and social responsibility without their report suffering.

I have difficulty with that

idea. I watched Buddhist monks immolate themselves in defiance of the

Thieu government. I found what these men and women did abhorrent. But

I would not allow my staff to editorialize and say, how horrible a waste

of life. By playing the story straight, describing what happened and

showing the pictures of the charred bodies, we did not compromise the

story, the reporters, or the monks, their beliefs and actions. Because

we could not expect families at home in America to fathom anyone taking

his own life that way, we simply presented the facts, no more, no less.

We maintained the art of storytelling by staying true to the event,

to what the reporter and his camera team observed and recorded. Whatever

occurred in the mind and heart of the viewer because of the report was

a bonus and, perhaps, a salve to the reporter’s psyche. The risk

was always that the correspondent might err too much on one side and

thus cloud his interpretation and unduly influence that of his audience.

Reporters can’t help but raise moral issues and taking a stand

when confronted with anything abhorrent. But we should take seriously

our role as purveyors of truth and clarity. The minute we try to serve

another muse, however tantalizing, we are no use to our audience.

In Vietnam, reporting for television was like nothing anyone had done

previously.

Television as the dominant mass medium did not exist in World War II.

Newspapers, magazines with their wonderful still photographs, and radio

dominated coverage. The occasional newsreel at the movie theaters featured

government-released film of the war. When our troops entered Korea,

where we sometimes euphemistically called the war a “conflict,”

television remained in its infancy and there were few combat film photographers.

Again, radio, newspapers, magazines, and newsreels containing official

war film supplied the coverage. Broadcast journalists in the Vietnam

War wrote a new set of rules that are still emerging and are far from

being perfected today; in the language of journalism, they are in “rewrite.”

These journalists combined eyewitness reporting, oral history, analysis,

and even elements of legend and myth. My hope is that we will continue

to fuse these diverse elements every way we can to allow them their

rightful place in the world of reporting.

We know the history of the Vietnam War, how it started perhaps naively,

and with a purpose that fit its time. Today few argue its worth. The

length of the war and the rising death toll changed attitudes toward

the war. Only time will tell if this second Iraq war will know the same

fate because of lengthy fighting or extended peace keeping. In the Vietnam

War we frequently heard about the "role of the press," a term

I found objectionable then and still do,. We exist to report what we

see and to present it in all its glory or ugliness to our audience.

We should always be tough-minded and accurate. At NBC News and the other

networks, and news bureaus, we covered the war with then state-of-the-art

equipment, yet we succeeded. Today that antiquated gear wouldn't have

a chance. People made their stories come alive despite the tools. People

were our strength then and will always be our strength in journalism.

However changed the technology, unless the reporter, print, still photographer,

TV or radio, has a good eye and a good ear with the right instincts

and training, all the high tech equipment available will make no difference

in the end.

© Ron Steinman

Buy the book: Inside

Television's First War

|

T

T I became the Saigon bureau chief for NBC News in April 1966 and servedfor

twenty-seven months until July 1968, thus becoming a part of the history

of the war in Vietnam. The reports generatedb y my bureau andall the

other news bureaus, broadcasters, wire services, magazines, and newspapers

defined the war then andfor generations of Americans to come. We didnot

know the effect the war wouldha ve on the future when we coveredit.

I became the Saigon bureau chief for NBC News in April 1966 and servedfor

twenty-seven months until July 1968, thus becoming a part of the history

of the war in Vietnam. The reports generatedb y my bureau andall the

other news bureaus, broadcasters, wire services, magazines, and newspapers

defined the war then andfor generations of Americans to come. We didnot

know the effect the war wouldha ve on the future when we coveredit.