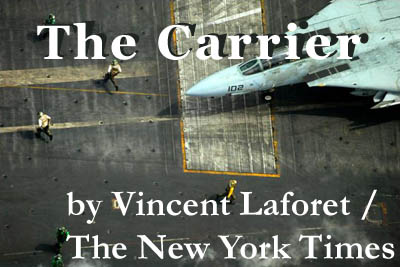

ABOARD THE USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN April 1, 2003 I boarded this ship with limited expectations of what we would be allowed to cover - I was skeptical about the military's agenda. At first, things went poorly on this ship. Journalists were required round-the-clock escorts - even for meals. This proved to be a huge logistical nightmare for us, as the people we photographed/interviewed, were visibly uncomfortable with having a Navy personnel overhearing every word, and as the Public Affairs office struggled to find enough bodies/volunteers to escort 30 members of the media - 24 hours a day - 7 days a week. All interview requests had to be done through the PAOs (Public Affairs Officers.) Our first media uproar occurred less than a week into the embed, when a few of the interviews were abruptly cancelled by the PAOs - one LA Times reporter was discouraged to write about on-board pregnancies. Such issues were unflattering to the Navy and off limits we were told. A quick e-mail campaign to Pentagon officials resulted in a significant turning of the tides. The PAO's office was told not to interfere with the aim or content of our coverage. I should clarify that the Navy does not read through or censor the content we send back at anytime - we are trusted not to make any mistakes and release sensitive information. By the second week, the Navy allowed the media to roam freely aboard the ship - only classified areas and the reactor were off limits - escorts were of course required on the flight deck, an area which has been described as the most dangerous 4.5 acres in the world. Spirits were up - and feature stories began to flow. Still photographers benefited the most - as the four of us were allowed to work on mini-essays which was a welcome relief from photographing endless waves of takeoffs and landing (which is what I think the Navy expected us to cover day in and day out.) Reporters remained frustrated however

- as rear Admiral John Kelly, the senior navy man in the fleet - was

extremely reluctant to release any information to them during the daily

press briefing on this ship. In fact it wasn't uncommon to have him

release information 24 hours after it had been aired on CNN, or in a

CENTCOM briefing in Qatar - with no further details. His priority was

clear - he was not willing to take any risks whatsoever in releasing

ANY information that might put his pilots or sailors in jeopardy - One further difficulty involved random

blackouts on this ship. These blackouts, referred to as "River

City" here, were without warning and had no specified durations.

We were not allowed to make any outgoing calls, send any e-mails, photographs

- anything. Doing so would result in a quick end to an embed position.

The reasons for the blackouts were clear - the Navy wanted to make sure

that editors back home would not guess that the war had started - when

all lines of communications suddenly went dead in the Middle East. Therefore

these blackouts became routine weeks before the start of Satellite connections are nearly impossible

out here - the ship makes constant turns at irregular intervals - as

they have to remain within a virtual grid in the Persian Gulf. The only

predictable thing is that the ship would line itself up with the wind

for take-offs and landings. Therefore by the time one was able to get

a sat signal and start to send a Overall my experience has been very rewarding

- albeit with a significant caveat. I have been able to tell the story

of the 5,500 men and women on this ship with relatively little interference

by the Navy. But it has been an extremely one-sided story - after all,

we can cover the bombs being assembled, loaded up, the planes taking

off - but we will never see the effect of those bombs from here. I do

find solace in knowing that I am part I think that most of the friction between

the media and the Navy - is a result of a fundamental misunderstanding

of what the other is trying to do - not out of mistrust or malice (although

there has been some of that at times - and a healthy amount of it in

my opinion.) The Navy wants to ensure secrecy and surprise - while the

media is looking to be the first to break the news. Af first, it was

apparent to me that the Navy did not understand that we were simply

trying to tell daily stories/features about the aviators One of the fundamental misunderstandings

by the Navy is their inability to comprehend that we need to witness

events happening - not learn of them after the fact. This is particularly

relevant to still photographers of course. As the first wave of aircraft

taking part in "Operation Iraqi Freedom" catapulted off this

ship - we were yanked off the flight deck for a mandatory meeting. The

PAO who pulled us off the flight deck had not been Also: Live television should simply be

banned from the front lines/embed process. They make it impossible for

the rest of us to do our jobs. Serious restrictions must be put on Live

TV - because they have little to no delay in what they report. Unfortunately,

we all have to live by the same rules - and no dispensation is given

to newspapers or non-live media -even though the pictures/stories have

no chance of making it to print for at In the end my challenge has been to try

and tell the story of the people on this carrier accurately and objectively

- to show the incredible sacrifices these men and women put in everyday

- while not forgetting what this is all about - what happens when those

bombs are released. |

||

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

THE

CARRIER

THE

CARRIER