|

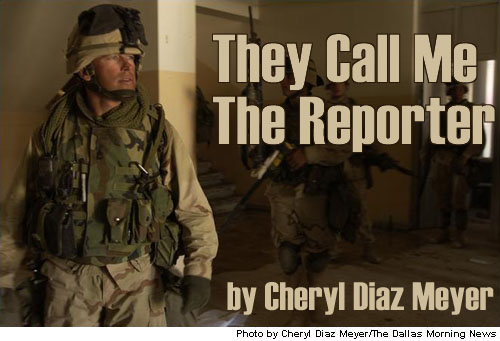

They Call me the Reporter

UNDER ATTACK April 5, 2003 Dear Family and Friends: A sickening WVOOOOOM! accompanied by a desperate call of INCOMING!!! woke me up from my hard won, battle-weary sleep. Tanks barreled up and down the dusty streets, artillery exploding in every direction with the cries of grown men injured in the fighting. In a fraction of a second, my poor, numb brain registered the sound of a 122 mm. rocket that landed only 20 feet from our camp and I thought, where do you get off lighting those things up so close to sleeping souls??? We were lined up in our sleeping sacks like mummies trying to erase the horror of the day’s battles that left three of our guys dead and another nine injured when the explosion awoke us, terror beating deep in our throats. We traveled some 31 miles yesterday, up and down a highway controlled by Saddam Hussein’s Al Needa division of the Republican Guard. Signs of fortification were everywhere, and we were met with machine gun fire and rocket-propelled grenades. My writer, Jim Landers, sank back at the end of the day mumbling something about having stepped into hell. I had barely extricated myself from my cocoon, popping my head out to check if the world still existed around me, when another rocket flew right over us again. I ducked with my hands covering the back of my head, as if that would somehow save me from its terrific power to kill. It sounded so close that I thought, had I been standing, it may have actually hit me. My heart was beating against my chest, and the anger and outrage of the attack was registering. The Lieutenant Colonel said the counter battery was tracking the source of the rockets and would immediately destroy them. We were lined up side by side along with the men of the Bravo command amphibious assault vehicle, with whom we had made a home for the past two days. We looked at each other in the dark, wide-eyed and shaky. Sergeant Jeffrey Hale came running over declaring that he was on night watch duty. He had been chatting with men from another AAV when the first rocket landed closest to them, sending shrapnel flying by them but no one was hurt. When the third one hit, I jumped out of my sack, barefoot, in shorts and a T-shirt. I collected my chemical suit, chemical boots, gas mask, Kevlar helmet, hiking boots, glasses and backpack and ran to the AAV for shelter. A young Lance Corporal, Keith Chandler, had barely covered up his skivvies with his sleeping bag to let me trample all over him and perch myself on top of an MRE (Meals Ready to Eat) box, cursing under my breath. Getting into the AAV with all my protective gear normally takes me about a minute of huffing and puffing, and Chandler watched in disbelief as I leapt effortlessly into the four-foot high entrance, throwing equipment in all directions. After thirty minutes in the AAV, we straggled out, shaken, ready to face our chances against an enemy that we could not escape. If we got hit, no armed vehicle would survive. I crawled back into my sack whimpering small comforts to myself. If it was going to happen, then it would happen, and hopefully it would be quick. The only thing running through my head as I waited for sleep to take me away from the misery and fear was that I didn’t care what it took-- just please make them stop. With each explosion of our artillery I cheered in my heart because it was one step closer to making me safer. I didn’t care who was hurt and what damage was caused. The following morning revealed a mini bus with a man, woman and two children lying in a pool of blood, a sedan with a man in the passenger seat covered in a blanket, a man lying prostate in front of a delivery truck, two men lying next to a car, one of whom was believed to be a three-star general in the Republican Guard and countless others at various checkpoints. The violence outside was almost matched by the violence inside my sleeping bag filled with the sour smell of sweat and body odor. Some five days ago, I scammed a couple of gallons of precious water where I scratched and scrubbed away over ten days of grime. In front of 50 men at the Command Operation Control center, I climbed the 11-foot high AAV and lowered myself into the engine compartment with a backpack and a water jug as curious stares followed my every movement until I was out of sight. The compartment is about eight feet wide and five feet tall, large enough for a grown man to work on the engine. It was painted and dusty, but not greasy like a car engine. I hunkered down and attended to the details. My only worry was the choppers that clipped overhead. It was one of the most delicious days of my travels thus far and I emerged a new woman. I have found a couple of Marines who know how to braid hair. My recent claim to fame is that a certain Second Lieutenant Joshua Grindstaff from Minnesota was helping me with my morning hair regimen when Colonel Oliver North walked by, talking on a satellite phone as he visited the Second Tank Battalion on behalf of FOX news. He commented under his breath that the Marines are a one-stop shop and that Grindstaff shouldn’t quit his day job. Perhaps not, but Grindstaff and a couple of other guys have been my saviors, keeping my long hair in check during these bad hair days. If my mother only knew that I have learned to do my business, (yes, that kind of private business) in plain view of hundreds of men, she would surely die. Part of my adjustment to living with the Marines is that I have adopted the very strategic use of a poncho. I can whip it out during a battle advance, do my business under my cloak and remove it in almost the same time it would take a man to do the same. I even use it at night when night-vision goggles can penetrate even the deepest of dark nights. After weeks of waiting for action, painfully bored and anxious, we seem to have gotten it “en force” with the Second Tank Battalion. Each day seems to be increasingly hectic as we race toward Baghdad, blowing through town after town of opposition, only waiting to resupply for ammunition and to evacuate the dead and injured. Admittedly, my stomach has been weak since last night’s close-call horror. Several of the journalists traveling with us have quietly begun talking about leaving. We are rattled and shaken. And the increasing violence to which we bear witness is taking its toll. For myself, I can only say that I am determined to see Baghdad, if my will permits. Love, THEY CALL ME THE REPORTER April 13, 2003 Dear Family, Friends and Colleagues, I’m sitting in the back of an amphibious assault vehicle and my stomach is turning, over and over. The cracking of the machine guns being loaded with magazines and the chic, chic, chic of pistols being cleared of dust is seeping into my thoughts. I look around with deliberation and my eyes rest on the stretchers hung behind me and the boxes and boxes of ammunition organized near the infantrymen lined up on a makeshift bench, half their bodies poking out of the hatch of the vehicle. My eyes focus on the words: “100 Cartridges, Cal 50, LC 92D621L437,” and I keep reading those words and letters and numbers over and over again, just because I can. I have control of that. It feels as if I may have joined a suicide mission. A few days ago, just as I had packed up my sleeping bag and my belongings, I found out that the infantry division attached to the Second Tank Battalion was leaving on a mission into central Baghdad. Word had filtered in that Fox Company 1/5 had faced terrible adversity in Baghdad with a number of casualties and Fox Company 2/5 was urgently summoned to Baghdad to help, perhaps to assist in the takeover of one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces. The sergeants were yelling orders and the men moved hurriedly to pack their meager belongings and prepare their weapons. The air was full of dust, pulsing with tension. I tried to glean information about the mission when my pal Rob Milford, our CBS radio reporter embed companion, encouraged me to go on the mission. Rob’s been my second pair of eyes on this trip and has often been the source of many of my photos. The people around me have made me a better journalist. I am surrounded by people who care, who look out for me, who share information. Serendipity plays a large part in my life and I have learned to listen to the subtle signs, not an easy task for someone like me who likes to be in charge. In Afghanistan, I missed the fall of Taloqan when I had to leave the country to resupply computer and camera equipment. In the end, I came back in time to cover the fall of Konduz, which ended up being a better story. Serendipity brought me to the Second Tank Battalion where as an embedded journalist I was one of the first to enter Iraq, eight hours before any of the other troops. I have also been one of only a handful of women journalists covering the war from the combat front lines. I approached Captain Terry Johnson, Commanding Officer of the Fox Company 2/5 Infantry Division, and asked if I could join his men on their mission -- and he agreed. I went through my minimalist mental checklist: two cameras, batteries, flashcards, gas mask, Kevlar helmet protective vest, water bottle, toilet paper. Check. Good to go, as Marines say. There have been a few times in the past few years that I have asked myself whether I am crazy for doing what I do, and this was definitely one of those times. If this was my last day, is this the life I wanted to live? I could die around men who don’t know me. I am as anonymous to them as they are to me. They-- in their camouflage uniforms, me—in my newfangled journalist khakis sewn custom by the finest military tailor in Kuwait. They call me The Reporter. Met by Cheering Crowds The men refer to themselves as grunts. Their uniforms are ripped from digging fighting holes. They are wild. They are trained to clear buildings, to combat the enemy at close range, to flush out enemy combatants and to secure the perimeter of encampments. They work like dogs. They are both courageous and insane. Water jugs are bouncing to the rhythm of our AAV tracks and one jug, with its top missing, squirts water onto my dusty boots. Staff Sergeant announces from under his communications helmet that we are taking sniper fire. “It’s starting,” says the corpsman, medic Cesar Espinoza, who promptly yells “Snipers!” to the grunts. The smallest grunt bends down from the hatch, “Huh?” “Snipers!” Like you!” “Oh,” says the grunt, who slowly lets the information sink in, then repeats the warning to his other mates. I watch every movement of these camouflaged men in the hatch, memorizing each glance passed from man to man, each movement with a weapon that is purposeful and practiced. Tension is evident in every limb, with an acute awareness of their surroundings. Every gesture seems full of meaning, and I feel every moment should be recorded for posterity, because if this mission goes bad any one of them may not make it. The words Blackhawk Down are whispered among them. We drove through Baghdad and ironically were met by cheering crowds. Families positioned themselves in the doorways to wave, smile and give us the thumbs up. Women stared in disbelief and pointed me out to other women, waving excitedly. In the past, during other battalion advances through villages, Iraqi women seemed relieved to see me, a woman, in the midst of all the camouflage. I suppose they figured the Marines must be civilized if a woman is among them. Chances of an attack were high in an urban environment where any tall building might have snipers or rocket launchers. The men remained on high alert until we arrived on the campus of Baghdad College. Hot tea in a kettle was discovered, two brand new looted diesel generators were parked near an office, a brand new pick-up truck in the lot went unclaimed and a puppy was found sleeping under a desk. The men discovered showers, bathrooms and running water and many took advantage of the facilities for bathing and laundry. The Poncho Queen At this stop, I ran into Letta, the New York Newsday reporter who still had cornrows on her head from before she left the camp in Kuwait March 18. Our conversation led to topics such as how she fared in the field regarding privacy needs. She had been embedded with several hundred Marines and apparently had been suffering, trying to restrict her needs until night time since we left the camp in Kuwait. But half the battalion is equipped with those pesky NVGs (night vision goggles). I shared with her the secret of the Poncho, to whom I must credit Master Guns Cordero, who took pity on me the first day in the field. To my embarrassment, I have been named the Poncho Queen of the Second Tank Battalion. The other day we made a five-minute “service stop,” in an area that was entirely flat. I picked the real estate in front of the vehicle. Three men lined up about twenty feet off to my right and like a choreographed scene, they glanced over their shoulders in unison, because there was Cheryl armed with her poncho. A Gentle Spirit and a Man’s Decision In the early morning blue light in the midst of green and khaki camouflage, I saw a young grunt with rosy cheeks resting on the ground on his elbows holding a rose to his nose, inhaling its delicate scent. I grabbed my camera and quietly began shooting pictures. He was not a boy and not yet a man. With green knit gloves, finger tips cut off, one pinky high in the air, grime embedded in every crevice of his hands, he raised the rose and into my frame appeared another Marine infantryman who bent down to share a deep breath of the flower’s perfume. I snapped several more frames, delighted to be a witness to this moment of gentleness. His comrades eyed me and began to make

fun of him, saying his reputation would be ruined. Another said that

perhaps he would be hunted down by women who might see the photo and

fall in love with his feminine side. Later it was revealed that he was

involved in the deaths of several Iraqi civilians when a bus tried to

run a checkpoint and barrel into the intersection near our encampment

by the town of Al Aziziya. I had photographed the aftermath of that

horrendous night where the bodies of a woman, man and two children lay

in a pool of blood on the floor of a mini-bus. Stunned survivors wept

in a nearby structure and awaited help from Navy medics. The bus that

the young infantryman and his comrades shot up was sandwiched between

two ammunition trucks, both of which had attempted to run the checkpoint.

Marines at other locations nearby were dealing with suicide bombers,

Republican Guardsmen and Fedayeen carrying white flags in one hand and

shooting AK 47s with the other as well as other guerilla tactics. That

was also the same night that three 122 mm rockets had hit just 20 feet

away from our encampment, the night after the battalion had fought through

a day-long ambush where the Marines lost three men and seven others

were injured. I know that I am supposed to be objective and tell the

news without bias, but I this war got personal for me that night. Near

death experiences can do that. After three rockets exploded near us,

the refrain “please make it stop...” kept repeating in my

head. And this young man did. The infantryman, not yet a man, had to

make a man’s decision. Had he not, I may not be alive today. I

was overwhelmed to hear his story. For me and for the rest of the battalion,

he will carry the burden of that night’s decision. He must live

with the memories of his actions and their results. In war, nothing

is black and white, but there is right and wrong. I know that my grunt

with the gentle spirit is a hero. The long days and long nights of convoys are over for today. I am leaving the Second Tank Battalion to settle in to central Baghdad where I will finish our photo coverage with stories of peacekeeping, policing and restoration efforts. The battalion has been camped in a military installation most recently used by the Fedayeen. It’s been pretty quiet since I returned to the battalion two days ago, but today an RPG landed in the midst of several humvees. Fortunately it did not detonate. A round of fire followed but no one was hurt. Just when things seem to quiet down, more crazies come out of the woodwork. I am sad to be leaving my pals here at the Second Tank Battalion. Near death experiences with others can be very bonding. They have given so much to me that I walk away feeling humbled and honored to have been a part of their efforts. They are brave men, surprisingly sentimental, tough.... Gentlemen. Wanting to reclaim my own rhythm April 15, 2003 I have arrived at the Al-Safeer Hotel in downtown Baghdad today, a bombed out fortress of a place that opened yesterday to accommodate the hundreds of journalists pouring into the city from Amman, Jordan and others exiting from weeks of military embedment. My room overlooks the Tigris River, and on the opposite shore, one of Saddam’s palaces. The transfer out of military life involved hours of waiting and moving from one Marine installation to another. In each installation, I was less than 10 miles from downtown Baghdad but had no way of renting a vehicle on my own with any degree of security. After surviving so many adventures for the past few weeks, hasty choices didn’t seem worthwhile. Weeks of being around other people every single moment of the day has been feeding a desperate need for privacy and the structure and routine of military life has left me wanting to reclaim my own rhythm and spontaneity. Love,

|

||

Enter

They Call Me The Reporter - by Cheryl Diaz Meyer

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |