| Dispatch:

Eight Days in Abu Ghraib

July 2003

by Molly Bingham |

|

I will

not forget when I first returned to Baghdad, walking the length of the

cool marble lobby to the elevators at the Palestine Hotel to go see

Seamus Conlan on the 8th floor and getting in the elevator alone with

a bell boy and his trolley. I had trepidation about entering the building

in the first place. It gave me the creeps to return to the place from

which I’d been taken on the early morning of March 25th. But I

was back, and I was going to see Seamus. Times were different. The regime

had fallen. My concerns that the boogey men who took me from my room

that night were still loitering around in the shadows wasn’t wrong,

but it wasn’t a reason not to return to work either.

There was a moment of silence in the elevator and I felt the bellboy

looking at me. I looked up and said, ‘Salaam’, to which

he simply replied, ‘You’re alive.’

‘Yes, I’m alive.’ He said he was so sorry. He saw

me taken that night. He had prayed for me. He had hoped I was ok. Over

the weeks since then I have encountered many people like that who had

seen me, or knew about my story and had felt unable to do anything on

my behalf.

I

had a plethora of choices on how to cover this war. I have been lucky

enough to have a plethora of choices in my entire life. In fact, the

only time I haven’t had choices, I think, was during the eight

days in Abu Ghraib prison, my life was out of my hands. I

had a plethora of choices on how to cover this war. I have been lucky

enough to have a plethora of choices in my entire life. In fact, the

only time I haven’t had choices, I think, was during the eight

days in Abu Ghraib prison, my life was out of my hands.

In the choices I had on how to cover the war there

were the following: Sit it out, too dangerous, not my cup of tea. Embed

with the US military. Go to Iran and pass to Kurdistan. Go to Syria,

and pass to Iraq somehow, but it was hard to really know if I would

be able to cross that border once the war began. I had a three month

multi-entry Kuwaiti visa. I could go to Jordan and try to go overland

to Baghdad either after getting a visa there, or when the war started

and the border would become more porous.

In the months since the drums of war had begun slowly

thumping in, say, August, I had, along with some close friends, constantly

talked about our choices. What equipment we should have, what might

happen. Whether being in Iran would be a good story, might Iran get

pulled in somehow. Would Kurdistan declare an independent state, throwing

the Turks into a tizzy, the Americans unwilling or unable to control

them, and setting the stage for the breakup of Iraq.

As time moved on, through January and February, I became

convinced that the US would attack from the south mostly, move north

and arrive at Baghdad and there, face an entrenched, committed group

of Iraq’s strongest military, and a few million civilians unwilling

to let the city fall. My guess was that rather than fight street to

street in Baghdad the US military would encircle it and put up a siege.

They would bomb and run missions into the capital, but they wouldn’t

try to take it. They would let it fall.

That was my best guess. And given that guess, I began

to feel more convinced, after months of thinking I didn’t want

to be in Baghdad for the war, that it was the place for me to be. The

place for me to go. It was the right part of the story to cover.

My professional situation was not fixed either, which

gave me more freedom. I was pretty sure that if I could get into Baghdad

before the war I would get an assignment. So all the preparation I’d

done, chemical suits, training, night vision equipment, atropine to

counter chemical agents, clothes for cold weather and the north, clothes

for warm weather and the south. Deciding to take a Leica and forty rolls

of film along in addition to the two digital bodies so that should the

dreaded ‘e-bomb’ be used by the American military that I

might still be able to at least photograph, even if I couldn’t

transmit. If everything I owned with a computer chip in it was disabled,

it would basically leave me with clothes, a water purifier, 30 bags

of turkey jerky and my Leica and forty rolls.

When I arrived in Amman with Marco from Rome Newsweek, AP and other

large organizations were pulling staffers out, telling them they had

been advised by the Pentagon to pull all of their staff out of Baghdad

for the war, that the bombing would be merciless and it was just too

dangerous. The people who stayed in Baghdad either managed to convince

their desks, ignored their desks, or were freelancers like me with no

one to answer to but themselves.

The night we got on the bus and made our way to Baghdad

I was very anxious. Marco and I had sat down the day before and I had

tried to talk to him about going. Should we? Should I? I had asked him

what he thought how he felt, but he had cut the conversation short saying,

‘Molly, I do not want to discuss this with you, this decision

has to be your own, I don’t want any part of your choice. You

know the risks, you know everything, we’ve talked it over many

times. You have to make your own decision.’

And how right he was. And that last night before we

left I stayed up all night kicking my head this way and that trying

to find a space where I was resolved either to go, and comfortable with

whatever consequences might follow, or big enough to pull off Baghdad

and say I didn’t want to do it and go North, or to Kuwait, or

go work on another story all together. I decided. I had come this far.

I had heard and known and thought about the risks for months. I had

done the training I could to prepare myself for what I imagined would

be the worst, a chemical or biological attack of some sort. But most

importantly, I felt very strongly that being in Baghdad was the most

important, significant place to be to cover the war, and the what happened

to the civilians there during the bombing, and that I had the capacity

to do that now; visa, preparation, timing, no boss to tell me I couldn’t,

and that these things had come together and I would go. So I did.

Through

the eight days I spent in Abu Ghraib I never once questioned the decision

I’d made, or wished I’d done it differently. That mental

preparation over the months, and that final night, making that decision,

somehow prepared me for being in prison. It is hard for me to know if

I would have felt differently if I was tortured, I may well have. But

as it is, as it was, the conviction of why I had been in Baghdad at

all, and what I’d come to do, that conviction was never shaken

in me, and I used it as my foundation every time I was interrogated. Through

the eight days I spent in Abu Ghraib I never once questioned the decision

I’d made, or wished I’d done it differently. That mental

preparation over the months, and that final night, making that decision,

somehow prepared me for being in prison. It is hard for me to know if

I would have felt differently if I was tortured, I may well have. But

as it is, as it was, the conviction of why I had been in Baghdad at

all, and what I’d come to do, that conviction was never shaken

in me, and I used it as my foundation every time I was interrogated.

After I was released and returned to New York I began

almost immediately to think about when I would go back. As I slogged

my way through a series of interviews in New York the question was always

posed to me, ‘will you go back to Baghdad?’ At first I thought

I’d only go in if I could go with US military. At that time the

war was still on, troops were still moving, and the statue of Saddam

had not yet been pulled down, symbolically ending the regime. Later,

I began to think I could go back in on my own. Johan went back in about

a week after we were released. Marco went back in a few days later.

I talked to Seamus twice and Marco about how they felt it was, if it

was safe enough for me to come back, did I risk running into some intelligence

guy who had arrested me, and might just kill me at the spot. Seamus

in particular, assured me it wasn’t like that, and that most of

those guys were busy saving their own skins, and had much bigger things

to worry about than me. I figured he was right.

Some friends said they thought I was crazy to return,

or to return so soon. But I decided I was keeping my own council on

this one, and that I would be able to feel when the time was right for

me.

But my biggest reason for returning was truly personal.

I had failed somehow to cover the story. I had become the story, and

being the story was the thing about the whole experience I liked least.

I wanted to go back and tell stories from a place that had had story

lock down for twenty years. So seventeen days after I was released from

prison I hired a GMC and started the fifteen hour drive back to Baghdad

from Amman.

I had an assignment from Glamour magazine to work on

a story relating to women, and I was trying to work out in my brain

what I wanted to work on. After all the talking I’d done about

my experience in prison, I began to think it would be the right way

for me to turn the focus back on the story, and away from me, for me

to go speak to some of the real Iraqi female political prisoners, ones

who had been held for years. Had they been tortured? What were their

charges? Had they been treated like me? Had they been held at Abu Ghraib?

By chance the first translator someone said they knew

who might be free soon was an Iraqi woman named Mona. As Mona and I

began working on the story it became clear that it would not be easy.

Women will not admit to having been in prison for it carries the assumption

that you have been raped, and a raped woman in the Muslim world will

find no quarter. She has no status, she will not be accepted. Some prisoner’s

families even killed them when they were released, I was told. But Mona

and I kept pushing on, asking at every place we could imagine to go:

the Vatican emissary, a hospital run by nuns, the International Committee

of the Red Cross, a prison guard at the women’s prison, Al Rashad.

Finally, after four days of footwork, we found a woman,

Suhad, who had been the Iraqi News anchor for twenty years, and whose

arrest 1989 and release six years later had been big news. She had been

arrested for mentioning in passing, privately, that if Saddam Hussein

was going to criticize America and George Bush, he might consider removing

the American cowboy hat he was wearing when he did so. For that statement

she spent six months in detention, was sentenced to death, had her sentence

commuted, and served five years of a life sentence in Al Rashad women’s

prison until she was released during an amnesty. She agreed to talk

with us, and as she told her story to me, I began to feel that the listening

was helping me untie some of my own fears and memories. Thinking of

my own feelings about my colleagues in prison, I asked her if her friendships

made in prison were important ones, and she said they were the most

critical.

She agreed to introduce me to a few of them, and Mona

and I returned the next day and we went to meet Tunis who had been held

in detention for eight months because of accusations against her mother.

Her brother later came by the house. He had also been detained eight

months, then served two years at Abu Ghraib.

From that first moment when Suhad had started telling

me her story several times I had wanted to burst out and tell her about

mine. Several times over the next week the women would say, ‘you

can’t possibly imagine what it’s like to be in solitary’,

or ‘you can’t possibly imagine the worst part is the detention,

when you don’t know whether you’ll ever see a judge, or

what your sentence will be. Once the sentence is passed you know your

fate, and that is somehow easier.’ Every time I wanted to say,

‘oh, but I do understand, at least a little….’ But

I didn’t. I talked to Mona after that first day and told her,

no matter how much I wanted to that I should not tell these three women

about my experience until after it was finished. I was afraid that if

they knew my story it would color their telling of their own, that there

were things that might go unsaid, a knowing nod seemingly enough to

explain something.

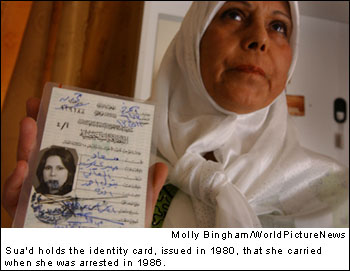

I spent the next two days talking to them, listening

to each of their stories. Sua’d had been detained for six months,

beaten, tortured with electric shock, hung from the ceiling by her arms,

but she said she had not been raped. She then served sixteen years in

Al Rashad prison and had only been released in the general amnesty late

last fall when all the prisoners were released.

Then

I had to ask them if I could photograph them, if they were going to

return to their prison and place of detention, if I could document their

returns. They were hesitant at first. Suhad, a public figure anyway,

didn’t have a problem with it. Tunis didn’t want to at all,

still feeling unstable 15 yrs after her eight months in detention. Sua’d

was reluctant. She didn’t want me to photograph her. But as Mona

and I talked more with them they agreed and we made the plans about

when they would go back. Then

I had to ask them if I could photograph them, if they were going to

return to their prison and place of detention, if I could document their

returns. They were hesitant at first. Suhad, a public figure anyway,

didn’t have a problem with it. Tunis didn’t want to at all,

still feeling unstable 15 yrs after her eight months in detention. Sua’d

was reluctant. She didn’t want me to photograph her. But as Mona

and I talked more with them they agreed and we made the plans about

when they would go back.

Then the next day we went to the detention center where

they had all been held during the same period of time in 1989. In the

hot midday sun we visited the building that had been destroyed, it was

on a street that had been full of intelligence offices before the Iraqi

Intelligence Service had had new headquarters built for them in the

1990s.

The day after that we went back to Al Rashad. Sua’d

showed me the cell she’d lived in for sixteen years. But the first

thing she did when she walked back into her cell for the first time

since the amnesty was look out a chink in the window and point out her

tree to me. I cried. I had had my own little tree out my own little

window at Abu Ghraib. As for me, Sua’d’s tree had been something

she focused on to keep her going. I stood with her in the window and

cried, still unable to tell her why I was crying.

I spent the whole day there with them, each telling

me their story, their memories of the time spent in prison. The guard

I’d talked to emerged, giving each of them wide hugs and crying,

smiling, so happy to see old friends.

We walked out of the ward and documents were emerging,

the young boys bringing files and files of names and lists and records.

They all looked through them, looking for their own names, names of

their friends. the documents were too old, from the 1970s.

When we were finished, I asked them all to go back

into the ward with me. A dust storm had kicked up and we were all dusty

and covered, and grit in our eyes, and I could tell they wanted to get

in the car and go home, tired and spent.

But the five of us, Mona, Sua’d, Suhad, Tunis

and I stood in the quiet of the cell and I told them I myself had been

arrested and held at Abu Ghraib. That that was part of why I had wanted

to do the story, that I thought people in America often took their political

freedom for granted, and couldn’t imagine the reality of what

it was like to be arrested for nothing and shut away for years. But

most of all that I really thanked them for telling me their stories,

for sharing so much of their time and thoughts with me, for letting

me find the similarities between us, the things we shared. Tunis’

chin dropped, Sua’d looked surprised. Only Suhad stood with that

same confidence looking at me. I told them I had wanted to do the story

because so much press had been focused on my colleagues and me during

our detention, but that I knew full well we were not the story, they

were. These women who had been treated fiercely by the regime, years

of their lives robbed from them were the real story, and I was very

grateful for the opportunity to tell it.

The one thing I didn’t anticipate in my return

was the incredible personal importance of overlaying my experience in

Baghdad and in Abu Ghraib prison with a new one. I had reluctantly been

part of the story for ten days, and I wanted very much to get back to

telling it, rather than being it. Had I not returned to Baghdad, I’m

sure it would have become a sort of mythical place, a house of terrors,

a boogey man in my mind. By coming back when I did I managed to slowly,

meticulously, day by day, paste over that experience with a new collage

of faces, voices and experiences. And for that I am very glad. The Iraqi

people have been wonderful. I have been welcomed into people’s

houses, into their lives, been told secrets of their feelings and things

they couldn’t mention for years, stories they locked up inside

their heads not even telling their friends. it is with great relief

that the place I have returned to is a place where most people feel

they can speak their mind to a stranger.

One

would think I might have a certain hatred of the regime, having been

arrested, etc, but, in fact, I find myself still critical of the war,

critical of the American presence here, its ineffectiveness, it’s

unwillingness to rely on the skilled and knowledgeable people of Iraq,

the seeming lack of respect for a culture thousands of years old, which

has borne the burden of a terrible despot for thirty years, a despot

who was, let us not forget, supported by the Americans throughout the

80’s. That seeming lack of respect sits hard in my stomach, and

I resist telling people I am American. One

would think I might have a certain hatred of the regime, having been

arrested, etc, but, in fact, I find myself still critical of the war,

critical of the American presence here, its ineffectiveness, it’s

unwillingness to rely on the skilled and knowledgeable people of Iraq,

the seeming lack of respect for a culture thousands of years old, which

has borne the burden of a terrible despot for thirty years, a despot

who was, let us not forget, supported by the Americans throughout the

80’s. That seeming lack of respect sits hard in my stomach, and

I resist telling people I am American.

There is a deep irony in an American Colonel giving

an interview, standing in a mass grave of Shias killed after the failed

uprising in 1991 and promising that his forensics team will collect

the data needed to prosecute the killers. That irony seems lost on the

Colonel, and apparently on the soldiers protecting him. But it is not

lost on the Iraqis digging their friends, families and brethren out

of a grave by their bare hands, carefully laying each body in a white

shroud, noting clothing and identity papers to help the families identify

them. As one Iraqi standing by told a journalist, ‘it’s

a pity the Americans didn’t come here twelve years ago’.

And as an American, the irony is not lost on me.

I appreciate the value of an Iraq, free to speak its

mind for the first time in decades. But that value will be diminished

if they are not allowed to do so. It will be no freedom at all, if the

Iraqis themselves are not allowed to shape their future, to rebuild

their country, to choose their leadership, even if it is a Shia government,

or the Ba’ath party. It is theirs to choose. And we must respect

that.

Footnote: I would like to thank all the journalists

who remained in Baghdad while I was a prisoner who pushed and pulled

the regime to try to get info about our whereabouts. That took real

balls and conviction, and I cannot thank them enough. I also again want

to thank my family, my sister, my parents, my friends, my colleagues

and the apparently huge number of people I have never even met who came

together on our behalf to ensure our safe release. The longer I am here

in Iraq, the luckier I realize we were, and the more I treasure these

continuing days I’ve been given. My many, many thanks.

© Molly Bingham

Molly Bingham is a freelance photojournalist.

She was taken prisoner in Baghdad March 26 with four other journalists

and released in Jordan eight days later.

Her portfolio can be viewed on the website of WorldPictureNews:

http://www.worldpicturenews.com

http://www.worldpicturenews.com/portfolios/index.htm

email to Molly Bingham will be forwarded to her from

this address: taraf@worldpicturenews.com

|