|

Cry Monrovia

by Chris Hondros

Monday

was a day of horrors in Monrovia. A massive artillery barrage was unloosed

Liberia’s capital city, artillery shell death falling from the

sky and killing anyone in the blast range when they landed. Journalists

in the press hotel were huddled in the lobby, wondering how to cover

this barrage, when the story came to us--a shattering boom, right outside.

Everyone ducked, and eventually I ventured out to see

a terrible sight—a boy, around 10, slowly dying in front of me,

his last gasps rasping as he laid prone on the ground, a pool of thick

blood spreading from his head, killed for the crime of trying to bring

a load of cassava leaves back to his family. The cassava leaves sat

beside him in the red dirt. Monday

was a day of horrors in Monrovia. A massive artillery barrage was unloosed

Liberia’s capital city, artillery shell death falling from the

sky and killing anyone in the blast range when they landed. Journalists

in the press hotel were huddled in the lobby, wondering how to cover

this barrage, when the story came to us--a shattering boom, right outside.

Everyone ducked, and eventually I ventured out to see

a terrible sight—a boy, around 10, slowly dying in front of me,

his last gasps rasping as he laid prone on the ground, a pool of thick

blood spreading from his head, killed for the crime of trying to bring

a load of cassava leaves back to his family. The cassava leaves sat

beside him in the red dirt.

I walked away from that tragic scene

just as another shell hit, this time across the street in a small school

compound about fifty yards away. Everyone scattered. It was chaos. I

ducked inside a concrete guard shack at the gate of the hotel, wondering

what I should do, as the barrage seemed endless. Finally I screwed up

enough courage to run the 50 yards to the door of the school. I wandered

in.

It was a vision of hell—wailing

children and women, crying men, blood, horror, fear. The shell had landed

in the middle of an interior courtyard, and it had directly hit a woman,

who’s mangled and lifeless body lay in the center of a radiating

blast pattern. The wounded and dead were everywhere.

I took a few pictures, but then realized

that no one was handling anything--that five minutes before, a mortar

round had landed here, and that the survivors were too dazed to do anything

at all. I was the first to arrive.

Do enough conflict zone photojournalism,

and eventually you grow accustomed to seeing the horrors of war. Though

usually, in even the worst tragedies, journalists have little role to

play other than in doing their documenting and reporting—aid workers,

soldiers, and locals do all the actual heavy lifting of saving and feeding.

But occasionally something happens that requires intervention.

“Is anyone doing anything

here? You need to get these people to the MSF clinic down the street,”

I said, loudly but to no one in particular. Dazed looks.

“MSF? You know MSF?”

Suddenly I realized that a lot of people might be half deaf from the

blast.

"Look, you two," I shouted to a pair of burly Liberians standing

by a wall in a daze, inconsolable but unhurt. "The wounded need

to be carried to the MSF clinic. Now!"

They said nothing for a moment, then snapped out of their reverie.

"But we have no car," one finally wailed.

"It's right down the street! Small small," I said, using the

Liberian slang to say something is close by. "Like this boy,"--I

motioned to a child with searing cut across his head--"and that

man there. Come on! Carry them!"

For a few minutes we went on like this, me playing triage coordinator

for this very small and macabre scene in the world’s ongoing tragedy

(or farce) of war. They made a move for the woman who'd been directly

hit, but I stopped them.

"Not her, she's dead," I said. "First the living people."

They passed over her motionless body and went on to tend a boy whose

leg had been perforated. Then many others, with a ghastly array of punctures,

amputations, and wounds. One by one the injured were carried out to

the MSF clinic a hundred meters away. Finally they were finished. We

huddled down inside their little shanty with dozens of others, fearing

another mortar strike on the courtyard.

"There is still the woman," one said.

"She's dead, I told you," I said.

He seemed confused. "But look," he said simply, motioning

to her through the window. And outside, the woman, who'd been directly

hit by a mortar shell and nearly sheared in two, was attempting to sit

up off the pavement. My head lolled down onto my chest in despair.

"Good God!" I muttered, and we ran outside. She was conscious

and moaning. Someone rolled over a wheel barrel, and we picked her up

and plopped her in. One of her feet, sickeningly hanging on by a flap

of skin, hung over the edge of the barrel, which was slowly filling

with blood.

After this, I walked back across the street to the hotel. The streets

were empty, as the shells were still striking in the distance and another

could land anywhere at any moment, but I was too spent to run. Lethargically,

I ambled up to the guard shack in front. The Liberian local militiamen

who patrol the hotel had watched the shell hit and the bodies emerge,

one by one.

I sat down, glassy-eyed and dazed. But they had no sympathy, only scorn.

"You see Liberia, white man? You see how we live?" I was mute

and communicated only with my eyes, like I'd just run a marathon. Then,

shaking my head, I walked up the hill to the hotel. Dozens of Liberians

and journalists were huddled against the walls of the dark, ground floor

lobby, like a huge litter of kittens in a tiny box.

No

one, it seems, wants to make the first move to help Liberia. No

one, it seems, wants to make the first move to help Liberia.

Americans least of all want to take any initiative. The cautionary tale

of Somalia is often trotted out, but you might as well discuss the parallels

to the Liberian conflict and the Revolutionary War. Somalia is an utterly

lawless land, full of Muslims with few ties to the West and where seemingly

every household is armed to the teeth and ready to fight. Liberia’s

population tilted much more to the West. Most Liberians are benign and

surprisingly well educated, with even refugee children in rags carefully

spelling out their names when you ask. Most different of all is that

Liberians are generally unarmed and are universally weary of war.

I had many versions of this conversation:

"What do you want to happen now in

Liberia?" I would ask.

"We want American troops to come and save us."

"If they come, they will probably send a small, peacekeeping force."

"They are welcome. But better will be a large number of soldiers."

"How long would you want them to stay?"

"Many years, if they like. We are tired of war. We want occupation.

We need

help. Even a small number of Americans will command respect."

Not a single person I talked to, from

refugee to businessman to teenaged soldier nervously fingering his Kalishnikov,

was against U.S. peacekeepers occupying Liberia.

It’s apparent to anyone who visits

that Liberia considers itself an annex of

the United States--the Puerto Rico of West Africa. Founded by former

American slaves in the 1800s, a significant segment of the population

is of American ancestry. The clues of its history--and its hopes for

the future--are

everywhere, from the Liberian dollar, which was tied to the value of

the

U.S. dollar until 1996, to the American flag bandanas sported on the

head of

many a child soldier. Around the country, neighborhoods and counties

have names like Virginia, Maryland, New Georgia, and West Point. The

government complex is called Capitol Hill. The main hospital is called

the JFK Medical Center. A high school is named after Richard M. Nixon,

which is so strange I’ve been too scared to ask anyone exactly

why. Even the Liberian flag is a direct knock-off of the U.S. flag,

so close that when they hang limply they are hard to tell apart.

Reminders of America’s ties to

Liberia are literally written on the walls and signs of Monrovia. In

one common billboard, a white hand and a black hand clinch in a handshake

and their sleeves run into the American and Liberian flags. (Under the

graphic it reads, optimistically, "For Peace and Harmony.")

In another, a small Liberian boy stands on a road talking with a tall

black Uncle Sam:

"We’ve come a long way, Big Brother, but it’s still

rough!. We are

suffering!" says the Liberian, his hand outstretched.

"For true?" answers the little balloon over Uncle Sam¹s

head, probably the

first time he’s used that particular locution of English.

Eternally expecting help from "Big

Brother" however--and eternally being

disappointed--takes its toll. The locals are getting restless. In one

of the hundreds of refugee camps that have sprouted up on the literal

roadsides since LURD encircled the capital, I met a man slumped in a

plastic tent, his only possessions being a tin can

used to burn coal for cooking and a thin reed mat. We talked about the

U.S. assessment team and whether or not he thought they’d find

the evidence they needed to recommend a military intervention. His answer

summed up the feelings of almost everyone I met. "We are dying

here, every day,” he said, tears welling in his eyes. “What

more to do they need to know?

It's

especially difficult to watch such gruesome devastation every day when

you know at least a short-term solution is easy. Five hundred Marines

in one of the vaunted Expeditionary Forces with helicopter support could

probably demolish rebel and government troops alike and would have Monrovia

secured in a matter of days. It's heartbreakingly sad to follow the

travails of a multi-billion dollar, 150,000 strong soldier attempt to

occupy a clearly reluctant Iraq, while another land, much closer to

America in history and culture, has to literally beg to be occupied

with the number of American troops that pull kitchen duty every day

in Baghdad. It's

especially difficult to watch such gruesome devastation every day when

you know at least a short-term solution is easy. Five hundred Marines

in one of the vaunted Expeditionary Forces with helicopter support could

probably demolish rebel and government troops alike and would have Monrovia

secured in a matter of days. It's heartbreakingly sad to follow the

travails of a multi-billion dollar, 150,000 strong soldier attempt to

occupy a clearly reluctant Iraq, while another land, much closer to

America in history and culture, has to literally beg to be occupied

with the number of American troops that pull kitchen duty every day

in Baghdad.

But for weeks now no one has been willing

to make any first moves, so Monrovians have had to endure hunger from

cut off food supplies, death from medieval diseases like cholera, refugee

camps, and stray bullets zipping all over town, cutting people down

every day. Most feared of all is the mortar barrages, death from the

sky that rains down once or day or so, randomly killing anything unlucky

enough to be nearby when they explode. These mortar fusillades, probably

more than anything, chased out about half of the press.

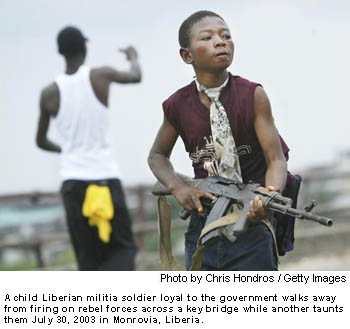

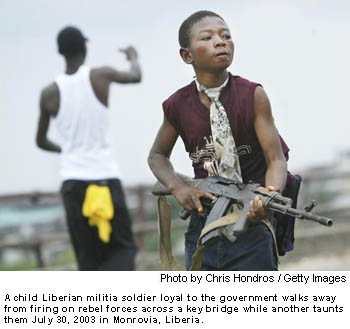

This latest assault was the third such

attack in two months, and this one is by far the worst. The anti-Taylor

forces of a group called Liberians United For Reconciliation and Democracy

have been waging fierce battles at the edge of town, mobilizing the

city’s dubious pro-Taylor government soldiers and militiamen,

whose only qualifications to fight are that they’re old enough

to lift a weapon. (Sometimes even that isn’t the case.)

But some of us journalists stayed,

wisely or no. There's an element of messianic here--politicians may

talk doublespeak and advisors might dither, but someone has to be around

to show the grim realities of life on the ground in Monrovia. Every

day this drags on, seemingly needlessly, dozens more people die—and

whether its preventable or not, people need to see it. No one’s

going to come out of this and complain, Rwanda-style, of not having

known. The facts on the ground at least are clear. Ultimately that’s

all the press can do.

© Chris Hondros

Hondros@aol.com

To

view the atrocities attributed to Charles Taylor's forces in Sierra

Leone, go to Martin Leuders' feature story at http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue9902/diary1.htm To

view the atrocities attributed to Charles Taylor's forces in Sierra

Leone, go to Martin Leuders' feature story at http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue9902/diary1.htm

|

M

M No

one, it seems, wants to make the first move to help Liberia.

No

one, it seems, wants to make the first move to help Liberia.  It's

especially difficult to watch such gruesome devastation every day when

you know at least a short-term solution is easy. Five hundred Marines

in one of the vaunted Expeditionary Forces with helicopter support could

probably demolish rebel and government troops alike and would have Monrovia

secured in a matter of days. It's heartbreakingly sad to follow the

travails of a multi-billion dollar, 150,000 strong soldier attempt to

occupy a clearly reluctant Iraq, while another land, much closer to

America in history and culture, has to literally beg to be occupied

with the number of American troops that pull kitchen duty every day

in Baghdad.

It's

especially difficult to watch such gruesome devastation every day when

you know at least a short-term solution is easy. Five hundred Marines

in one of the vaunted Expeditionary Forces with helicopter support could

probably demolish rebel and government troops alike and would have Monrovia

secured in a matter of days. It's heartbreakingly sad to follow the

travails of a multi-billion dollar, 150,000 strong soldier attempt to

occupy a clearly reluctant Iraq, while another land, much closer to

America in history and culture, has to literally beg to be occupied

with the number of American troops that pull kitchen duty every day

in Baghdad.