| My Mother

Never

Imagined I would be a Platypus

August 2003

by Patrick J. Sloyan |

|

Rolling

around on the tennis court for a low-angle shot, I realized that my

subject—the pro at the Pierpont Inn tennis club—was talking

but not into the headphoness attached to my Canon GL2. I sat up on the

court and slapped the earphones. Nothing. Rolling

around on the tennis court for a low-angle shot, I realized that my

subject—the pro at the Pierpont Inn tennis club—was talking

but not into the headphoness attached to my Canon GL2. I sat up on the

court and slapped the earphones. Nothing.

The tiny mike attached to the pro’s tennis shirt was not transmitting

sound to my awesome digital movie camera. What was worse was the realization

than my interview minutes earlier with the pro that would serve as the

voice over for stunning pictures of him in action was non-existent.

For, I had recorded him on the same mike that was clearly dysfunctional

on the tennis court.

Whether it was from rolling around in the sun or the pressure of the

Platypus Workshop Exercise No. 2, I was now dripping. There was only

two hours to produce an edited three-minute piece (or was it three hours

to produce a two-minute piece?) Suitable to network television. Time

was running out.

I was the only writer in a collection of men and women who were making

the transition from the increasingly difficult world of still news photography

to the limitless horizon of digital film journalism. Life is rough on

the cutting edge.

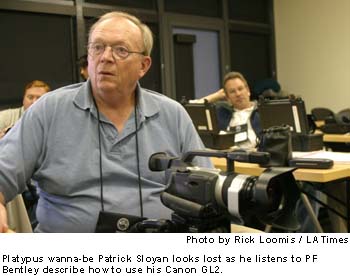

It got worse when I returned to the Brooks Institute of Photography

where the Platypus Workshop was held June 21-30. One of the senior instructors,

P.F. Bentley, ripped into me for not spotting the mike problem sooner.

I had failed to wear the camera headphone during the interview with

the tennis pro. They had been draped around my neck. “Put them

on your ears,” Bentley barked.

He rolled an elevated seat into the middle of the classroom, dimmed

the lights and showed my wandering footage. Instead of the remote mike

picking up the sound of the tennis pro, the camera ‘s built-in

microphone recorded my groans as I rolled about on the tennis court.

With every groan, my colleagues roared.

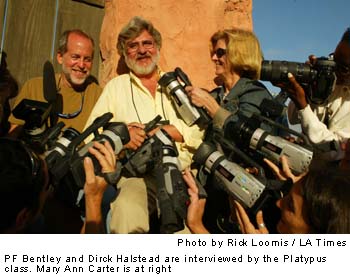

Dirck Halstead savaged the footage. Ostensibly, the piece would portray

the pro’s work with children. “Not one picture of the pro

handing a racquet to a kid,” Halstead said as I squirmed on the

hotseat. Humiliation is easier to handle when it is passed around to

your peers. Halstead and Bentley poured it on during those early exercises.

Bumbling along was Rick Loomis, who won National Photographer of the

Year for his Iraq coverage for the Los Angeles Times. Struggling was

Brian Van der Brug and Geraldine Wilkins, also Los Angeles Times staffers.

Meri Simon of the San Jose Mercury violated every bit of direction is

filming her voice-over interview; know in the film business as A Roll.

Mary Ann Carter of Indianapolis, Ind., and Mariella Furrer of Narobi,

Kenya—both freelancers—seemed unable to ask questions that

produced answers from filmed subjects.

Bit by bit, day by day, we all got better.

The

humor of Bentley and reassurances by Halstead along with their coaching

and insights produced dramatic improvements. “I was once right

where you are now,” said Halstead, recalling his transition from

a Time magazine news photographer to a documentary filmmaker. “You

will get better.” The

humor of Bentley and reassurances by Halstead along with their coaching

and insights produced dramatic improvements. “I was once right

where you are now,” said Halstead, recalling his transition from

a Time magazine news photographer to a documentary filmmaker. “You

will get better.”

The careers of Halstead and Bentley, also

a Time veteran, provide a foundation for these workshops named after

the Australian animal that has survived for 110 million years by adapting

to a changing habitat. Both thrived on the riches of Time, Inc., for

decades when the magazine need color photographs to balance color advertising

during the printing process.

Once digitization and pagination took over at Time, the color ads could

be printed individually without need for balancing news photographs.

Suddenly, the princes of the photography staff were under the gun. Rather

than submit to a new contract and lower wages, Bentley and Halstead

walked away. Halstead now teaches at the University of Texas in Austin.

Bentley on the staff at Brooks.

Their careers were on display during evening sessions of the Workshop.

Halstead’s work of 40 years was contained in a 10-minute film

mainly of stills from Vietnam and Washington in brilliant color. Bentley’s

coverage of national political campaigns has that grainy black-and-white

quality that adds a dramatic dimension.

The lifestyles of Halstead and Bentley, the First Class airline seats,

the golden overtime, the bonuses and other benefits have evaporated

for most of the younger photojournalists. The New York Times, the Washington

Post and most every major news magazine have adopted pay and reproduction

policies, which have virtually squeezed out freelance photographers.

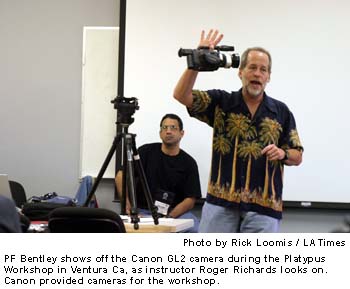

At Platypus, photojournalists learn to seize the very digital technology

that has so depressed their profession. Canon, Sony and other camera

makers are producing movie cameras for $2,500-$3500 that are on equal

footing with network and studio machines costing $30,000 or more. The

advent of digital film editing has turned the Powermac G4 and Final

Cut Pro 3 into a tool once found only at major studios. Step by step,

each student learns how to plan a film; use lighting and tripods; plan

and execute A Roll interviews; scramble for B Roll footage that is the

heart of the film; write a script and edit. Each person becomes an entire

camera crew—producer, cameraman, soundman, and editor.

One goal: plan and complete a documentary that will be purchased by

ABC Nightline. Halstead, Bentley and past Workshop graduates have become

Nightline contributors.

One goal: plan and complete a documentary that will be purchased by

ABC Nightline. Halstead, Bentley and past Workshop graduates have become

Nightline contributors.

Halstead and Bentley look past Nightline when cable news and drama shows

will be hungry for the work of frontline journalists who can handle

movie film and well as stills. Future demand maybe endless. “Good

TV is what we are shooting for,” said Bentley. “There is

a beginning, a middle and an end. Keep it focused.”

Proof that Platypus produces could be seen in the final exercise: A

five-minute project that required pre-approval by the staff and a script.

Of course there is always a ringer in these events. Bryan Chan, a staffer

with the Los Angeles Times, has worked with his own Canon GL2 and editing

setup before coming to Ventura. His work was almost professional from

start to finish, including a noisy stone sculptor and a Ventura city

worker in charge of cleaning graffiti off of town walls.

More surprising was Alan Lessig, a photographer for the Army Times in

Washington, D.C. Lessig’s initial footage of a teenager at a skateboard

park was somewhere between dopey and insipid. But his final edit was

a dazzling display of entertaining gyrations. “You’ve made

a silk purse out of a sow’s ear,” said Halstead.

My personal favorite was Brian Van der Brug’s backcountry blacksmith

with sounds and close-ups that evoked the art and the smells of a bygone

profession.

“It’s TV,” proclaimed Bentley of the blacksmith epic.

My final exercise dealt with the captain of boat that takes campers

from Ventura harbor to the Channel Islands. Halstead and Bentley castigated

it. The only kind words came from Roger Richards, a veteran still and

film photojournalist who also runs the Digital Filmmaker website. He

admired my footage of passengers oohing at leaping dolphins. “You

did a good job tracking that dolphin,” Richards said by way of

a consolation comment.

For me, however, the Workshop was a step inside the inner workings of

filmmaking. To hell with TV. A documentary that will likely win something

really big . I’ll show Bentley and Halstead. Now, I should sketch

out some remarks…

“I want to thank the members of the Academy…” Now,

if I can just make Final Cut Pro behave.

©2003 Patrick J. Sloyan

Contributing Editor

ppsloyan@starpower.net

Sloyan is a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter who has covered national

and international events since 1960. |