|

A

co-production between the Digital Journalist and American Photo

|

||||

As wars go, the initial Iraqi campaign last spring was the Mother of All Superlatives. Conservative stalwart William Bennett insisted it would "go down as one of the greatest military efforts of all time. "One Washington pundit termed it "the fastest military advance in the history of warfare." On the other extreme, a Middle Eastern website branded it "The Most Foolish of Wars," while Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak warned it would eventually create "one hundred bin Ladens"." But whatever else it was, superlative and less so, Gulf II, as none before it, has been a war waged and wagered with images. Every aspect of the conflict has seemed refracted,

in some manner, through a lens. During the heaviest fighting, the U.S.

military relied extensively on photo-based technology. News crews brought

digital cameras into battle in unprecedented numbers. Mourners and protestors,

politicians and propagandists brandished pictures of the slain or the

maimed to assuage their grief or stoke their ire. And everywhere, global

oglers have looked on, beneficiaries of advances in digital photography,

satellite transmission, and the ubiquity of cable and network TV. For me, the sense that gadgetry was evolving at truly

warp speed came on April 9, the day I listened to a message on my cell

phone from photojournalist Seamus Conlan, on assignment in Iraq for

People. Conlan left me a breathless, buoyant voice-mail, which

I retrieved in San Francisco while sitting, of all places, at a sun-splashed

Giants-Padres baseball game. "U.S. troops arrived in the center

of Baghdad," I heard him say, describing events that occurred 90

minutes before. "They tore down the statue of Saddam Hussein. They

chopped his head off. They put a rope around his neck. And people rode

on the head of Saddam through the streets!" My only regret is that

he hadn't been able to punctuate his elation with a photo zapped across

the ether on a new-model picture phone. (In the interest of full disclosure:

I am currently advising Conlan's photo agency, World Picture News.) Mike Smith couldn't disagree more. Says Smith, New York Times deputy picture editor during the early stages of the military engagement, "We saw a war in a way we hadn't before, by numbers [of photographers] we never had before. And they did a great job. I think in general the photography was pretty highquality."

Circling above these fleets, arrays of satellites took spy shots, helped steer missiles, and sent weather data to the waiting laptops of Yanks in tanks. (Many of these soldiers' hometown papers, in fact, ran satellite pictures of Iraq right next to the local five-day forecast, linking readers visually and vicariously to the conditions affecting far-flung troops.) By way of comparison, Vice President Richard Cheney told The New York Times that during the first Gulf War, in which he served George H. W. Bush as Secretary of Defense, military leaders had used "maps, grease pencils and radio reports to plot [troop] movements. Now, even in combat vehicles, they click with mouses, and watch the war unfold on video displays." Photography has played a vital role on the ground as well. Soldiers don night-vision scopes and carry packs of playing cards bedecked with mugshots of America's Most Wanted Iraqis-- a memory trick for acquainting G.I.'s with their quarry. They photograph and videotape their own Special-Ops raids, such as the much-touted rescue of POW Jessica Lynch, the better to disseminate their story their way. Even the war planners themselves have been visually tethered; at President Bush's briefings, for instance, Tommy Franks, the Gulf-based general who had commanded the coalition until recently, would routinely appear, Oz-like, on a monitor in the White House Situation Room or at Camp David, "virtually" transported to meetings through the magic of Secure Videoteleconferencing. (The Internet's forerunner, ARPANET, in point of fact, was actually a Defense Department creation.) As the military evolved in photographic sophistication, so has the broadcast media. Yes, U.S. TV coverage has been sanitized (rarely showing casualties) and generally partisan ("I have been shocked," said the BBC's editorial chief Greg Dyke, in Rolling Stone, "by how unquestioning the American broadcast-news media has been. . . .We can't afford to mix patriotism and journalism.") But when it came to image-supply during the most explosive stages of the war, the network and cable stations were prodigious. Day and night, they cut from rooftop views of luminous billows over Baghdad to neon-green night-vision scenes to stunning videophone reports, transmitted in real-time from blurry perches on advancing tanks. Some commentators, impressed by the raw power of such footage, referred to these herky-jerky glimpses of desolate towns and desert landscapes as "real reality TV." These rough-hewn dispatches fell short, however. A nation at war needed to see and experience something less ephemeral, in a medium that promised a modicum of substance--and humanity. And American television responded, time and again, by presenting the work of still photographers. News programs began running the equivalent of war-zone slide-shows. Anchors lauded the succinctness and potency of the photographic frame. ABC's Good Morning America introduced a daily "Picture of the Morning." Even the CNN crawl-line paid homage to pictures, as the phrase "TODAY IN PHOTOS: A LOOK AT THE WAR ON CNN.COM" could be spotted trawling the cathode shallows. Oddly enough, here was a TV network using a teletype-era news-ticker to nudge viewers to log onto the Internet to access a batch of still photographs. This reliance on pictures pleasantly surprised photojournalists like James Nachtwey, who covered the war for Time. "In the past," he says, "stills were used when there was no video available because someone intrepid had gone somewhere with a camera that no one else had. But [in Iraq], even though there was a lot [of tape on hand], TV used photography. They'd discovered that sometimes still photographs can be more compelling in telling a revealing, human story."

Websites, newsweeklies, and book publishers rose to the occasion. Traffic spiked at picture-rich digital news portals. Time devoted as many as 16 uninterrupted pages an issue to full-bleed photo essays. By late spring, editors at Life, Time, NBC, Channel Photographics, HarperCollins, and PowerHouse announced plans for war-themed photo books. Photojournalist-filmmaker David Turnley packaged his pictures and on-line field diaries for The Digital Journalist into a Vendome/Abrams title. A book tracing the arc of conflict from 9/11 to Iraq is being released in November by the fledgling VII photo agency, whose members produced distinguished work during the war. * * * With this elevated headcount came increased risk. Joel Simon, deputy director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, told The New York Times that Gulf II was, quite simply, "one of the most dangerous conflicts [ever] covered." For the 1,000 reporters and photographers in the field (more than 600 of them embedded), the fatality rate topped 1 percent, compared with .1 percent for allied forces. Fourteen correspondents died in the war's first few weeks compared with 17 in the three-year course of the Korean War. Embedding itself was roundly criticized. Among the objections: too few correspondents had access to the action or to Iraqi citizens' points of view; journalists, thus confined, were missing "the big picture"; the Pentagon was controlling the news and making photographers beholden to (and therefore unduly sympathetic toward) the troops in their viewfinders. "Somebody expressed 'being embedded' as being indentured," says Fred Ritchin, acting chair of New York University's photography and imaging department. "The Vietnam War was covered by photographers who would make up their own minds over a period of time, [sometimes] years. They would go deeper and make pictures reflecting that. Pictures were earned." In Iraq, Ritchin believes, embedded photographers played the role of photo-illustrators, purveyors of a pre-conceived vision of the war. "You could either illustrate the point of view of the government--or not. The price paid for being embedded was giving up one's independent judgment. If it were a movie, it would have been scripted as Good versus Evil--World War II, in color. Nuance. . . was missed. Historians are going to be very, very critical of the coverage." Nonetheless, the system was superior to the journalistic straight-jacket applied in previous U.S.-led campaigns such as Grenada, Panama, and Gulf War I. "The military was shrewd enough," says The New York Times' Mike Smith, "to let photographers get close and do what they do best. They made friends with their subjects. They saw what really happened. I don't think [embedding was set up] for any noble reason. They did it to avoid the criticism they'd received in the first Gulf War [where] you had censors deciding whether or not your pictures could be seen. In this war, you could [transmit] just about any picture you shot, unless American soldiers were wounded or dead. In which case you had to wait two or three days for their families to be informed. Which is fair."

It should be pointed out that non-embedded photographers operated at the mercy of their Iraqi "minders." Despite these constraints, many of them were resourceful enough to return with remarkable views from the war's epicenter. One sensed shock, if not awe, in pictures of the allies' nighttime barrage of Baghdad, especially in the pyrotechnic tableaux caught by Agence France-Presse's Ramzi Haidar. As he had in Afghanistan, Magnum's Luc Delahaye, on assignment for Newsweek, shot in eerie, epic format with his Hasselblad XPan, a rather controversial camera selection for a newsmagazine. The images he made have a chilling formality, like desert dioramas. Delahaye rendered coalition troops as would-be toy soldiers; huddled clusters of detained Iraqis appeared to be tiny human pawns in a vast global death-match. Some photographers, in fact, were able to isolate moments of tragic grace amid the horror. Corbis' Olivier Coret's landscape detail, showing how a stream of blood had turned a roadside rut to crimson, seemed as vivid and primal as a scene from Bunuel. Photographer Lynsey Addario, also of Corbis, made evocative and textured images that seemed like auguries: angry Istanbul protestors set against a sky teeming with birds; Iraqis stooped like field hands, combing through a harvest of plastic-bagged cadavers. Her study of four women in black shrouds haunting a village road in northern Iraq recalled ethereal images by turn-of-the-century Photo Secessionists (such Edward Steichen) and later pictorialists like Leonard Missone. And yet it has been the pictures of unremitting civilian anguish that continue to resonate around the world. Karim Sahib, of AFP, photographed an Iraqi man grieving beside his mother's coffin, having lost several relatives when an allied-force helicopter reportedly attacked their car. Time magazine's Christopher Morris was on hand when a young boy, frozen in fear and bathed in a sandstorm's amber gloom, raised his hands to surrender, within inches of a G.I.'s rifle. Chris Helgren, of Reuters, caught the stunned faces of a well-dressed Iraqi family dashing past a bombed-out Iraqi T-55 tank. For millions, however, the brutality of the war was embodied in the image of 12-year-old Ali Ismail Abbas, first photographed by Yuri Kozyrev for Time. Ali Abbas lost both arms--and his mother and stepfather--when a missile struck his house in April. Immobile, bandaged, and badly singed, he peered from front pages, across news wires, and on anti-war posters. CBS called him "a symbol of Iraqi suffering." Pictures of this innocent boy, unimaginably maimed, prompted outpourings of sorrow, anger, and compassion the world over. Within days, he was brought to Kuwait for surgery. (As of this writing, Ali is in a physical therapy program there.) Observed John Fleming, editor of the Anniston (Alabama) Star: "That still photo...tells the difficult naked truth. This war has caused unimaginable pain to simple, ordinary people....Still photography in the right hands can define an event more accurately than days upon days of film footage and volumes of the written word." *** "All propaganda," said George Orwell, "is lies." Indeed, Orwell might have argued that image distortion, on both sides of this conflict, served to further fracture a woefully divided world. Not that the world needed pictures to polarize it--or to convince one side of the other's hypocrisy. From the Bush administration's perspective, Saddam Hussein's regime thrived on deception. It misled U.N. inspectors, secretly supported al-Qaeda, and stockpiled weapons of mass destruction. Much of the rest of the globe, on the other hand, believed that America and its allies must have been harboring a hidden agenda in waging its war. Why else would they abandon diplomacy (after having first sought the consensus of NATO, Russia, and the U.N. Security Council), part ways with major allies, and preemptively invade an oil-rich, Muslim country? In this hostile climate, pictures became levers of bias. And the administrations themselves set the tone. When White House image-masters wanted to present George Bush in a forceful light, for example, he slipped into a flight suit, took the controls of an S-3 fighter, and landed on the deck of the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln. Some Democrats charged that the visit, at an estimated cost to taxpayers of around $1.1 million, was staged with the express purpose of tripping photographers' shutters. The resulting money shot showed Bush as America's Top Gun, helmet at his hip in counter-Dukakis glory--suitable for framing during the 2004 reelection campaign. (A line of green-clad Aviator Bush action-figures, modeled after the photos, was actually released in August by Blue Box Toys--for $39.99 a doll.) Though Republicans rebuffed criticism of the trip, contending that the president was merely expressing his gratitude to U.S. troops, and citing similar forays by photo-hungry Democrats, this much was clear: throughout this war, the commander-in-chief has been in command of the camera, as savvy in controlling the conflicts's image-flow as was his Teflon forebear, Ronald Reagan. By the same token, Saddam's minions were earnest, if hapless, purveyors of their leader's image. They managed world opinion, and forestalled civil strife at home, by disseminating a stream of video clips. Shortly after the first U.S. salvo in March (directly targeting the Iraqi chief) state-run TV aired a sequence showing a haggard Hussein. Later tapes purported to reveal him meeting with aides and greeting throngs of supporters in the streets. Like Osama bin Laden before him, Saddam was being kept alive--and rendered statesmanlike--through video intravenous. In time, U.S. intelligence sleuths, by comparing the street-rally footage "with satellite photographs of the same neighborhood on the same date," according to The New York Times, "concluded that the tape was made before the war began." Identical clips of Saddam, in Rashomon-fashion, took on antithetical meanings. "You'd have the same picture and it would be three different truths," remembers Dorothee Walliser, publisher of the American book division of French publisher Hachette. "On Italian TV, Saddam would be alive: There's the picture. On U.S. TV, Saddam would be dead, implying it was a false video or one of his doubles. On French TV, it would be unconfirmed."(In August, Pentagon PhotoShoppers gave American soldiers doctored images of Hussein--in turban, with graying goatee, clean-shaven--to help them recognize the fugitive leader in different guises. Around the same time, humorous posters popped up around Iraq, briefly, showing a Mock-Saddam--as Elvis, as Rita Hayworth, and, curiously, as a Baathist Billy Idol.) The month before, when Hussein's sons Uday and Qusay were killed in an allied ambush, it was pictures and pictures alone that provided proof of the brothers' grisly end. According to CNN, the Pentagon handed out images of their bullet-scarred cadavers, on convenient CD-ROM, "through the provisional authority in Baghdad. . . .The CD also include[d] X-rays said to show wounds Uday Hussein suffered in a 1996 assassination attempt. These X-rays helped U.S. forces identify [his remains]." Even so, some Iraqis still claimed that the pictures were fabricated or the corpses misidentified. To counter such contentions, American commanders allowed photographers and TV teams to have at the pair, in Newsweek's words, "as they lay groomed and shaved, stitched up and waxed." The act of choosing (and the manner of displaying) particular news photos and videos--balancing acts even in peacetime--have become acutely politicized over the course of the war. When stations first broadcast scenes of U.S. POWs, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and others charged that the footage violated provisions of the Geneva Convention (forbidding mistreatment of captured combatants). Yet the U.S. press offered its own steady diet of images in which Iraqi captives were clearly identifiable: soldiers with their hands shackled or stripped to their briefs or cowering under drawn guns. One group of Palestinian students told The Washington Post's Molly Moore: "U.S. officials are being duplicitous. 'They show footage of Iraqi war prisoners,' said Jumana abu Sneineh, a 19-year-old physical therapy student. . . 'Do Iraqis look better than Americans?' " Rarely did U.S. screens show the bodies of the war dead, from either side. (ABC's Ted Koppel, for one, seemed to chafe at this trend, telling The New York Times, "We need to remind people in the most graphic way that war is a dreadful thing.") Qatar-based al-Jazeera, in contrast, aired footage of carnage with abandon, as a way of conveying what its editors considered "reality" and, critics might say, as a way of pandering to viewers' antipathy toward U.S. policy. Media-savant Michael Wolff commented in New York magazine: "It's pretty hard to adequately describe the level of bloodiness during an average al-Jazeera newscast. It's mesmerizing bloodiness. It's not just red but gooey. There's no cutaway. They hold the shot for the full viscous effect." Inventive captioning and extreme juxtapositions let media outlets give the news their own spin. Morocco's Al Alam newspaper ran an inflammatory caption under a photo of two U.S. soldiers: "Americans plunder and steal the money of Iraqi civilians." One of Rumsfeld's press conferences, according to Newsweek, was "split-screened by al-Jazeera with a wounded girl in an Iraqi hospital bed." Wrote Susan Sachs inThe New York Times, "Horrific vignettes of the helpless--armless children, crushed babies, stunned mothers--cascade into Arab living rooms. . . .[T]he daily message to the public from much of the media is that American troops are callous killers." Abdel Moneim Said, of the Cairo-based Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, told Sachs, "The media are playing a very dangerous game in this conflict. When you see the vocabulary and the images used, it is actually bringing everybody to the worst nightmare--the clash of civilizations." In the U.S., bellicose Fox News, considered by analysts to have helped define--and amplify--the patriotic tone of American TV coverage, was still no match for MSNBC when it came to using images to pluck viewers' heartstrings. Prior to commercial breaks, the cable channel would sometimes run a montage of inspirational stills and videos (flags flapping, warplanes prowling) as the voice of President Bush rallied the nation. MSNBC also concocted its own military photo mural, dubbed "America's Bravest," a mawkish display that exploited two touchstones of the 9/11 grieving process--the homemade memorial walls that sprang up across New York and Washington, and the term that New Yorkers had used to honor their fallen firefighters. And as the war has dragged on, with raids and sweeps continuing, with new bombings and acts of sabotage each week, photographs crystallize the sense that this conflict (now variously called a guerrilla war, a jihad, a war of attrition) has no clear end in sight. When a truck bomb destroyed the U.N.'s Baghdad headquarters last month, the images of urban rubble seemed channeled from a recurring news-wire nightmare: Beirut's U.S. Marine barracks ...Saudi Arabia's Khobar Towers ...the African embassies ...the World Trade Center. Even more directly, it is the occasional image of an Iraqi casualty or funeral procession, or the formal portrait of a slain U.S. or British servicemen, that remind us that the proper measure of this war's cost has come not in dollars or oil or imagery, but in human lives. * * * If a single picture-sequence served as the war's political Rorschach test, it was that of April 9, when a statue of Saddam tottered and fell in Baghdad's Firdos Square. That one event signaled the collapse of Hussein's reign, and prompted reactions from every quarter. Gen-X commentator and editorial cartoonist Ted Rall wrote in an on-line essay: "The stirring image of Saddam's statue being toppled. . . turns out to be fake, the product of a cheesy media op staged by the U.S. military for the benefit of cameramen." Photography sage John Loengard also expresses skepticism. "It was telling," he says, "that the event we remember the war by took place in front of the hotel in Baghdad where all the press was hunkered down." Statues fall, Loengard shrugs. He posits "the toppling of George III in Bowling Green. And history forever onward. Some czar was toppled in St. Petersburg. Many Stalins and Lenins bit the dust in the last [few] years. Unfortunately, things that are perfectly meaningful and symbolic [can be] something of a cliché." Not exactly, said New York Times columnist William Safire. The morning after the fall, he published an editorial in which he charged the scene with his own political valence: "Just as video of human suffering understandably triggers demonstrations against any war, unforgettable images of the jubilation of enslaved people tasting liberty drive home the wisdom of just wars."

So emblematic was this event that it could best be put into context by addressing it in terms of imagery. Here was the supremacy of the still photograph endowing a moment with historic consequence. One wonders: Would a regime have fallen in the desert that day if a camera had not been there to record it? *** © David Friend |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

As

television coverage was transformed, so too was print. Due to the legion

of photojournalists at the front, the digital pedigree of their cameras,

and the speed with which they could transmit images, the distributors

of visual content--photo agencies and wire services, newspaper syndicates

and web-platforms--offered up pictures by the bushel. In turn, newspapers

across the nation devoted double-page spreads to full-color photographs,

as they had in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks. There were

even the occasional news coups consisting of vivid descriptions

of unpublished pictures; these ran the gamut from the horrific (torture

shots confiscated from government archives) to the bizarre (a Caligula-like

photo-cache found in the house of Saddam's son Uday, which reportedly

included shots of call girls and tearsheets of George Bush's twin daughters,

Jenna and Barbara, dressed up for a night on the town).

As

television coverage was transformed, so too was print. Due to the legion

of photojournalists at the front, the digital pedigree of their cameras,

and the speed with which they could transmit images, the distributors

of visual content--photo agencies and wire services, newspaper syndicates

and web-platforms--offered up pictures by the bushel. In turn, newspapers

across the nation devoted double-page spreads to full-color photographs,

as they had in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks. There were

even the occasional news coups consisting of vivid descriptions

of unpublished pictures; these ran the gamut from the horrific (torture

shots confiscated from government archives) to the bizarre (a Caligula-like

photo-cache found in the house of Saddam's son Uday, which reportedly

included shots of call girls and tearsheets of George Bush's twin daughters,

Jenna and Barbara, dressed up for a night on the town). For

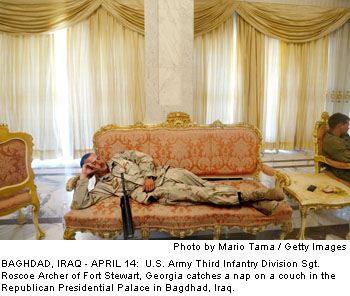

all its faults, the embedding process helped yield a surfeit of images

from photojournalists of every stripe--not just the marquee-name combat

photographers. One chilling picture of slain Iraqi troops huddled in

a trench (by Jon Mills of the U.K.'s Western Daily Press, embedded

with the Royal Marines) was reminiscent of similar images taken in World

War I. A heartbreaking photo of a woman pinned in a crossfire and clutching

two children in a ditch (by Dallas Morning News photographer

David Leeson, assigned to the Army's 3rd Infantry Division) echoed a

snowswept scene shot in 1940 by Life's Carl Mydans during a

Soviet air-raid over Finland. And who could miss the parallels in the

degrading moment witnessed by Bahram Mark Sobhani (of The San Antonio

Express-News) showing a line of Iraqi POWs, each with his bare

left shoulder numbered in Magic Marker? (Once Baghdad fell, the contrast

of prosaic and decadent was best depicted by Getty's Mario Tama in his

image of an infantryman napping on one of Saddam's brocaded couches;

Aurora's Ashley Gilbert even photographed a Marine sliding down a marble

banister in an ornate palace in Tikrit.)

For

all its faults, the embedding process helped yield a surfeit of images

from photojournalists of every stripe--not just the marquee-name combat

photographers. One chilling picture of slain Iraqi troops huddled in

a trench (by Jon Mills of the U.K.'s Western Daily Press, embedded

with the Royal Marines) was reminiscent of similar images taken in World

War I. A heartbreaking photo of a woman pinned in a crossfire and clutching

two children in a ditch (by Dallas Morning News photographer

David Leeson, assigned to the Army's 3rd Infantry Division) echoed a

snowswept scene shot in 1940 by Life's Carl Mydans during a

Soviet air-raid over Finland. And who could miss the parallels in the

degrading moment witnessed by Bahram Mark Sobhani (of The San Antonio

Express-News) showing a line of Iraqi POWs, each with his bare

left shoulder numbered in Magic Marker? (Once Baghdad fell, the contrast

of prosaic and decadent was best depicted by Getty's Mario Tama in his

image of an infantryman napping on one of Saddam's brocaded couches;

Aurora's Ashley Gilbert even photographed a Marine sliding down a marble

banister in an ornate palace in Tikrit.) Whether

epic or hyperbolic, the incident proved that at certain junctures in

history, the still photograph, resilient and universal, can be more

eloquent than words. "Nothing can in any way at this moment get

in the way of these dramatic pictures," proclaimed NBC's Tim Russert.

Newsweek, in an image meant to evoke similar frames of spontaneous

public euphoria--taken when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989--devoted a

three-page gatefold to Ilkka Uimonen's shot of a mallet-wielding man

blasting away at the statue's pedestal. And R.W. Apple, Jr., who has

reported for The New York Times from 100 countries, described

the instant in terms of a classic Life magazine picture of

a previous watershed event: "Not since Alfred Eisenstaedt documented

the end of World War II with his iconic shot of a sailor locking a nurse

in extravagant embrace in Times Square has the United States enjoyed

a similar catharsis."

Whether

epic or hyperbolic, the incident proved that at certain junctures in

history, the still photograph, resilient and universal, can be more

eloquent than words. "Nothing can in any way at this moment get

in the way of these dramatic pictures," proclaimed NBC's Tim Russert.

Newsweek, in an image meant to evoke similar frames of spontaneous

public euphoria--taken when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989--devoted a

three-page gatefold to Ilkka Uimonen's shot of a mallet-wielding man

blasting away at the statue's pedestal. And R.W. Apple, Jr., who has

reported for The New York Times from 100 countries, described

the instant in terms of a classic Life magazine picture of

a previous watershed event: "Not since Alfred Eisenstaedt documented

the end of World War II with his iconic shot of a sailor locking a nurse

in extravagant embrace in Times Square has the United States enjoyed

a similar catharsis."