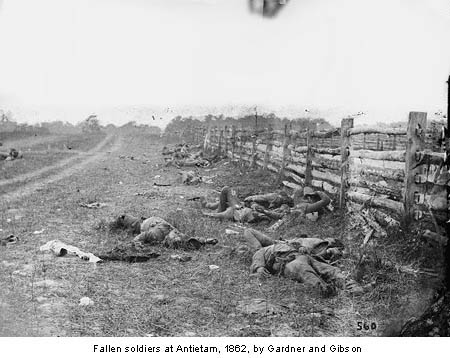

From the millions, maybe billions of photographic images over the past two centuries, how does one select those that picture significant historic eras? Beginning with Nicephore Niepce’s dim image of a barn roof and pigeon house in 1827, thousands of photographic images leap to mind. Realistically, any attempt to make a definitive selection of photos boils down to an individual’s opinion. However, this is also a reflection of the connections and disconnections that created an impact on the collective memory of Americans. Europeans, Africans and others beyond our borders may have a different perspective of photographs that represent historic events and trends. Clearly, a number of images remain transfixed in our national consciousness that are representative of change in our American culture and democracy. Of the many deserving images, here are a few that represent momentous shifts in our nation’s history. Death in the American Civil War The American Civil War received extensive photographic coverage and unleashed a flood of innovations and precedents. Matthew Brady became the most famous Civil War photographer, but hundreds of others covered the battles, campgrounds, devastated cities and the impact of the war. Just as people stand in long lines for concerts today, contemporaries of the Civil War stood in line to view eyewitness images of the troops and battlefields. Wars, whether small or large, became part of the visual record. Death and destruction appeared in a mass media format. Dead southern and northern soldiers from the 1860’s provided graphic images of the true nature of armed conflict.

In September 1862, "The Dead of Antietam" appeared on a sign outside Brady’s New York studio. Shocked and curious visitors stared for hours at photographs of battlefield corpses after the battle of Antietam, the deadliest single day of the entire war. The 6,000 dead and 17,000 wounded from the September 17, 1862 battle numbered four times the total casualties suffered by Americans at the Normandy invasion in June 1944. Brady’s dramatic photographs marked the first time most people witnessed actual images of the widespread death and suffering of the war. The New York Times said that Brady brought "home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war." Brady received criticism in the press and from the government for the graphic nature of some of his work. But he continued his labor at the battlefront until the final days of the Civil War. Photography and Investigative Journalism

In 1888 the New York Sun published twelve drawings from Riis’ photographs as part of his article "Flashes from the Slums." The purpose of these surprising images displayed "as no mere description could, the misery and vice that he had noticed in his ten years of experience ... and suggest the direction in which good might be done."

Riis gained his place in history as a documentary photographer and reformer. Riis utilized the immediate story to provide information with much broader ramifications. He provided a face on the unseemly underside of unfettered capitalism and industrialization. He also was a pioneer in a movement that would utilize photography to expose and advocate needed social and economic reforms. The muckrakers of the early twentieth century and the investigative journalists of the current century utilized the model of Jacob Riis to combat crime, poverty, racism and other ills that plagued American society. Pearl Harbor and the End of Isolationism

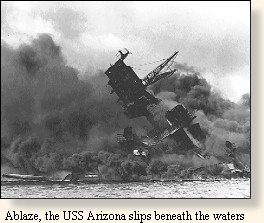

World War II is universally perceived as a just war to combat the militarism and fascism of the Axis powers, primarily Germany and Japan. The war also brought prosperity to a nation that had struggled for more than a decade with an economic depression that threw millions of Americans out of work and created a dangerous political climate that threatened the foundations of the our own democracy. Few people realize that in the years leading up to the war, the nation remained focused on its domestic struggles. Most American ignored international events and adhered to traditional isolationist sentiments that sustained most Americans. Not until Germany invaded Poland in September 1939 did Congress release an arms embargo and begin to give serious consideration to national defense. As the war raged overseas, Franklin Roosevelt struggled to expand efforts to aid Britain and the few remaining obstacles to Nazi Germany. Many newspapers, prominent politicians and popular Americans accused Roosevelt of dragging the nation into another European war. The Japanese bombardment of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 dramatically changed the attitudes of Americans. As the smoke billowed over the once peaceful harbor, any illusions that the United States could remain isolated from the war quickly disappeared. The destruction at Pearl Harbor represented the death of the idea that America’s geographic location and democratic history would make the nation immune from outside attack. The unanticipated blow demonstrated that even though Americans believed that their society and government epitomized democratic ideals and personal opportunity, other people and nations maintained starkly different views on citizenship and individual rights. The Modern Civil Rights movement In a nation that proclaimed “all men are created equal” in its own Declaration of Independence, life was anything but fair and equal if you happened to be a minority. African Americans in particular suffered from discrimination and segregation throughout the nation. But the issue of race and segregation dominated all life in the American South. Since the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction, the problems between white and black Americans remained an open wound that never healed until the arrival of the modern Civil Rights movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s. After World War II, the battle for civil rights erupted in full force, primarily on the city streets in the southern states. With the Supreme Court’s decision in the historic Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision in 1954, communities, churches, families and organizations divided over the thorny problem, but the vast majority remained opposed to lowering the wall of segregation – much less tearing it down. Southern blacks could not attend white schools, drink from public water fountains, receive fair treatment in court, participate in elections and enjoy the basic rights of citizenship most Americans took for granted. Well-publicized clashes erupted in Mansfield, Texas, Little Rock, Arkansas, Selma, Alabama, and many other communities. However, most newspapers, especially those in the South, failed to recognize the longstanding problem or feared to confront the obvious. The handful of southern editors who challenged the status quo witnessed a backlash and suffered a firestorm of criticism from readers and advertisers.

A year after Martin Luther King’s speech, and following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Bill. The next year, the Voting Rights Act became law. Just as important, the nation finally came to grips with its past and its record of discrimination. Racism would still be firmly rooted within American society, but the most reprehensive elements of Jim Crow segregation and racial discrimination came crashing down in the 1960’s. © Patrick L. Cox, Ph.D. . |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

During

the Civil War, Matthew Brady converted his fashionable New York and

Washington portrait studios into a wartime documentary of still life

photos. Setting a precedent that would be later followed by newspapers,

newsmagazines and television, Brady sent photographers into the field

in record numbers to provide extensive documentation of the great conflict.

During

the Civil War, Matthew Brady converted his fashionable New York and

Washington portrait studios into a wartime documentary of still life

photos. Setting a precedent that would be later followed by newspapers,

newsmagazines and television, Brady sent photographers into the field

in record numbers to provide extensive documentation of the great conflict.

Robber’s Roost, Hell’s Kitchen, a Downtown Morgue, and a Black and Tan Dive. In late nineteenth century New York City, Jacob A. Riis, a Danish immigrant and police reporter in New York, launched a personal campaign to expose the misery of the underprivileged who resided in New York City’s dangerous tenements of the lower East Side. In doing so, his writings and his photography provided a spark for future generations of investigative journalists. Earlier exposes by journalists had detailed the poverty and dangers of American cities. Photographs explicitly captured the dimensions of the tragedy.

Robber’s Roost, Hell’s Kitchen, a Downtown Morgue, and a Black and Tan Dive. In late nineteenth century New York City, Jacob A. Riis, a Danish immigrant and police reporter in New York, launched a personal campaign to expose the misery of the underprivileged who resided in New York City’s dangerous tenements of the lower East Side. In doing so, his writings and his photography provided a spark for future generations of investigative journalists. Earlier exposes by journalists had detailed the poverty and dangers of American cities. Photographs explicitly captured the dimensions of the tragedy.

The early work led to Riis's famous book How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890 and his next book, Children of the Poor. The narratives and pictures in these volumes offered stark depictions of human suffering that heightened public awareness of life in the emerging urban, industrialized society.

The early work led to Riis's famous book How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890 and his next book, Children of the Poor. The narratives and pictures in these volumes offered stark depictions of human suffering that heightened public awareness of life in the emerging urban, industrialized society.

Studs

Terkel named his oral history of World War II The Good War. Tom

Brokaw called the participants The Greatest Generation. World

War II clearly takes its place as one of the definitive conflicts in

world history and launched the United States into its modern day status

as a super power.

Studs

Terkel named his oral history of World War II The Good War. Tom

Brokaw called the participants The Greatest Generation. World

War II clearly takes its place as one of the definitive conflicts in

world history and launched the United States into its modern day status

as a super power.  By

the 1960’s, the segregation dam began to crumble. Martin Luther King,

Jr. addressed hundreds of thousands of marchers in August 1963 in Washington,

D. C. and told the nation – “I have a dream.” The stories often avoided

the truth and the long history of discrimination. But photographs and

television advanced the civil rights struggle onto the screens into

American homes. Policemen swinging clubs at innocent people, attack

dogs snarling at children, fire hoses turned on civil rights protestors

offended the sensibilities of Americans who took pride in their notions

of democracy and fairness.

By

the 1960’s, the segregation dam began to crumble. Martin Luther King,

Jr. addressed hundreds of thousands of marchers in August 1963 in Washington,

D. C. and told the nation – “I have a dream.” The stories often avoided

the truth and the long history of discrimination. But photographs and

television advanced the civil rights struggle onto the screens into

American homes. Policemen swinging clubs at innocent people, attack

dogs snarling at children, fire hoses turned on civil rights protestors

offended the sensibilities of Americans who took pride in their notions

of democracy and fairness.