|

|

|||||

|

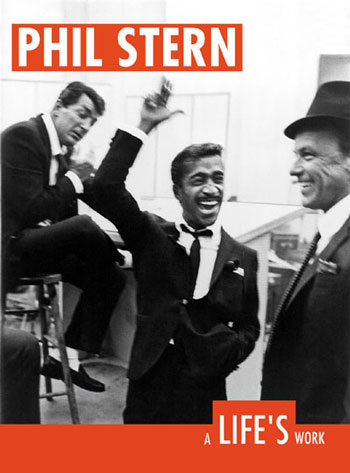

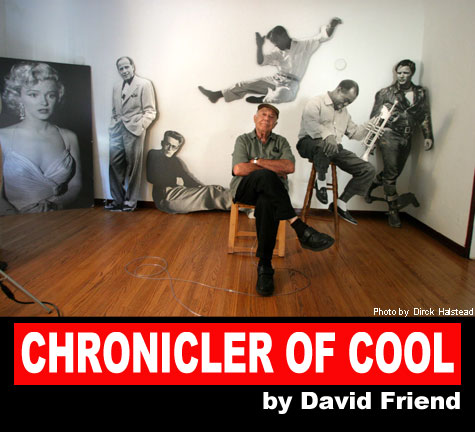

Sammy Davis, Jr. in his dressing room, lost in a cigarette's reverie. Liza Minelli pushing half-sister Lorna Luft in a stroller. Frank Sinatra, in white-tie, offering a light to JFK at the new president's inaugural ball. The photographs of Phil Stern, intimate chronicler of Hollywood and the jazz scene, convey an ease of access and an insider's collusion that are virtually unknown in today's Potemkin-village L.A. Back in the 40s, 50s, and 60s, before publicists ruled by fiat and photo op, certain superstars understood that when a charming guy with a camera came to call, the coolest thing to do was just to let him hang out. They recognized the value, and street-cred, that came from a behind-the-scenes photo essay in a glossy picture magazine. And so they often gravitated to straight-shooting Phil Stern, who worked for Life and Look and Colliers. (Indeed, the cover of his new book, Phil Stern: A Life's Work, from powerHouse, is designed with bold red-and-white graphics in order to approximate the cover of the old, weekly Life.) Studio moguls like Sam Goldwyn and Jack Warner let him into their inner sanctums. So did jazzmen like Art Tatum and Dizzy Gillespie. And supernovae such as Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando, and John Wayne.

Stern took a back-alley path to the Hollywood back lot (and, later, to the secluded dens of jazz's giants). In his youth, he says, his Depression-era family lived "one step ahead of the sheriff," bouncing among the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Washington Heights. While a student at Manhattan's Stuyvesant High, Stern swept floors in a Canal Street photo studio, worked the night shift at the unconscionably noir Police Gazette (taking pictures for $2.50 a pop), then shot for the left-wing journal Friday. During World War II, he enlisted in the Army photo corps and covered campaigns in North Africa and Italy, returning to his second home, Hollywood, not as another soft-focused dandy polishing the stars, but as a streetwise documentarian, more attuned to the world's grit than its glamour. He developed what Robert Cushman, photography curator of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, calls an "in-your-face style" and an instinct for nabbing undoctored moments "that was honed by covering war." Over the course of his long career, Stern ended up stalking some 100 film sets (Citizen Kane, A Star is Born, West Side Story) on assignment for various studios and magazines. "I call him the Cartier-Bresson or Robert Frank of Hollywood," says noted Los Angles photography dealer David Fahey, a Stern confidant. "He wouldn't allow the orchestrated P.R. photograph. He made authentically real photographs, and in the context of Hollywood, to make a real picture is odd."

In a sense, Stern not only helped create a more laid-back brand of celebrity photo but also contributed to his era's visual vocabulary of cool. In the process, Stern became widely known for his jazz portraits, photographing 40 album covers for Verve and becoming a fixture at studio sessions with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. Indeed, some of his best images of musicians and movie stars feel like breezy duets played through both ends of a lens. They impart what often seems to be his subjects' hat-cocked complicity in the act of posing off-guard or suave or downright down-home for their nervy pal: Duke Ellington trimming his moustache; Bette Davis bar-b-queing wienies; Sinatra wolfing down a backstage lunch. Sinatra, in fact, instigated several Stern photo sessions. He enlisted his friend to take pictures at President Kennedy's inaugural party in 1961 and, on occasion, persuaded Stern to create a faux photo or two. In one, Stern remembers, he shot "Sinatra literally in the position of Christ nailed to the cross. He choreographed it himself. This was a personal gag created for Mervyn Leroy, a director he had contempt for. He sent it along with a note that said, "O.K., you now have me where you want me. Frank." Come the 70s and 80s, Stern confides, "My career was sort of in eclipse. I was not getting assignments." Then he received a call from Spy magazine, the irreverent journal of urban ego, launched in 1986. He credits Spy with rescuing him from sure obscurity. Stern soon realized he could mine his archive and, as he says, "recycle my youth. Spy was tickled pink with the stuff I do. They published the back view of stars Richard Attenborough, Jimmy Stewart, Hardy Kruger pretending to piss into the sand dunes on the Yuma, Arizona, set of Flight of the Phoenix. They ran that as a double-page spread." Stern's star is again aglow. He recently donated the best of his Hollywood photo trove to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Virtually every page of Phil Stern: A Life's Work -- with its delightfully daunting heft (eight pounds, 1.5 ounces), giddy and outsize cover, and way-cool slip-case -- gives notice that, to Stern, access, and trust, meant everything. "They're happy pictures," says former Life editor Daniel Okrent. "Phil was nice to have around so the stars he's shooting seem relaxed. The secret to his work is that Phil's a sweetheart. It's as if he lit his pictures with his own personal sunshine." Stern's sunshine was never brighter than at daybreak one March morning in 1955. One of Stern's most famous shots -- of James Dean astride a Triumph motorcycle -- came about after a chance meeting on Sunset Boulevard, when Dean's bike swerved in front of Stern's Pontiac, then took a rough spill. "I cursed him out," recalls Stern, describing how the biker got up from the pavement, dusted himself off, and introduced himself as James Dean. "We ended up having coffee and apple pie at Schwab's."

© David Friend

David Friend, Vanity Fair's editor of creative development, served as director of photography of Life. In September, he wrote about Edward Steichen (for Vanity Fair) and the blues photography of Dick Waterman (for Smithsonian magazine). This piece is an expanded version of a story from the current issue of American Photo. |

|||||

|

Write a Letter to the Editor

Join our Mailing List

© The Digital Journalist

|