|

I Have Seen the Future

December 2003

|

|

|||||

|

My mother died in August, but before you rush to the nearest Hallmark store for that touching remembrance card, let me tell you that if we all live as long and die as easily as she did we'll be very lucky. She was 93, and to within three weeks of her death, when she was taken into hospital with a broken hip, she lived actively and independently in her own bungalow. Her biggest passion was to go on vacation with my Auntie Lily, which she did several times a year. They would take bus tours of British seaside resorts in February, places that I wouldn't visit in July, but by choosing the less hospitable months they got the good off-season rate. This enabled them to afford an oceanfront room where they would consume the half a bottle of whiskey that my mother took and the half a bottle of gin that was Lily's contribution, and there they would watch the world go by.

My mother was also a sports fan in the original meaning of the word fanatic. She would watch literally any sport on television and could reel off the soccer league listings with impressive accuracy. She was equally accomplished in the stats of tennis, rugby, cricket, golf and track and field; even equestrianism and fencing did not escape her scrutiny. I always thought that had she been born thirty years later she would have had a very different life, including the somewhat sobering fact that I might not have been around to tell you about it. What she did have was a very different old age from that of her parents. It was not only longer but it was also richer, with a refusal to accept the limitations that age imposes unless there was no alternative. When she was 92 she ordered a new bed, to which Lily's reaction was: "What are you doing a thing like that for at your age?" Her response: "If I want a new bed I will have a new bed" defined her approach to her final years.

If the book is illuminating about the future of old age in America, an interview with the photographer that produced it was equally illuminating about the future of photojournalism in America. Kashi is an intense but humorous man with a remarkable degree of focused energy that bursts from him. He talks like a Kalashnikov in the hands of an expert marksman, combining a rare balance of passion and pragmatism, idealism and realism. He understands in today's world where the confluence of creativity and finance is to be discovered. Through his talent and commitment, as well as with the vital support and talent of his wife, Julie Winokur who is the writer for the book, he has constructed a paradigm for working that not only serves him and his wife well, but which can be used by others as a model for emulation. His approach to supporting himself and his family as a documentary photographer in the twenty first century starts with the premise that he has no alternative. Despite what he sees as a radical restructuring of the media companies that doesn't favor the photojournalist he says, "There are people like myself who have no choice but to continue doing this kind of work and I'm not going to let this restructuring stop me." But in order to implement this commitment he has to start from a position where anger and self-pity are eliminated from the landscape and replaced with realism and acceptance.

"What's the use of sitting around and complaining? That doesn't make pictures and that's not going to convince anyone to do anything with your work. If I'm going to be remembered it's not going to be for all the day rates I do, or frankly for the stories that I do on assignment for major magazines, it's going to be for the personal work. It'll only be OK when I get my ass out into the field, find something to be passionate about and make the pictures."

Two grants made all the difference. One was from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which describes its mission as being dedicated to improving the health and health care of all Americans; the other was from the Project on Death in America, an initiative of the Open Society Institute, which is a part of the Soros Foundation. It describes its commitment as being "to understand and transform the culture and experience of dying and bereavement through funding initiatives in research, scholarship, the humanities, and the arts, and to foster innovations in the provision of care, public education, professional education, and public policy." Clearly what Kashi and Winokur were undertaking fitted directly into the agendas of both organizations.

The other key moment in the development of the project was as the result of publication by a media company, but one that would not have happened had Kashi not made what many photographers would consider an unacceptable compromise. In June of 2001 Brian Storm, who at the time was Director of Multimedia at MSNBC, offered them a five part series on the company's web site. The problem was that he could only pay them $3,500 for the entire package. Now I know from the postings that I read on the various photographer discussion groups that this amount for five major photo essays would likely bring forth a storm of outrage, for after all, doesn't the MS of MSNBC stand for Microsoft, and isn't this yet another example of Bill Gates trying to screw photographers? Even our intrepid documentarians had their reservations. "Julie and I thought this is worth $35,000, and we're giving you five major essays for $3,500. Then we realized, you know what, this is as good as you get, let's do it. In retrospect, boy, were we given a lesson because we might have only got a minimal fee for the usage but they put in probably twenty to thirty grand of web design, and the impact of it was huge."

The series got over a million hits, won for the authors several awards as well as invitations to lecture at conferences and other venues on the subject of aging, and not to a photographic audience. For Julie and Ed the outcome was immensely satisfying:

"OK so this is what it's about, this is why we're doing it, not only so that we get the signature spread in the New York Times Magazine, or I win POY or World Press, and I did get those things as well. But the most gratifying thing is when you're asked to present this work to people who are not in the photo world or the media, and they look at it and they look at you and they go ‘Wow, finally someone is doing something about the world we live and work in every day.'"

Not only did Bill Gates not screw this photographer but also Kashi readily acknowledges that of the ten or so agencies that he allows to license his work, Corbis has become the highest producing. "Corbis has become my best selling agent, and this is part of the restructuring of things. There's no point in sitting back and bitching about how it used to be or how you want it to be. I think you need to deal with how it is."

His recognition that he has to get his ass out into the field if he's going to make his career work enabled him to take risks earlier this year that paid healthy dividends.

"I went to the middle east for the war. My plan was to go back to Kurdistan through Turkey but I couldn't get through and I got detained in Turkey. While I was stuck there Wired Magazine called me with an assignment because I had my studio email several editors saying ‘Ed's in Turkey and available for assignment work" and the next thing I know I'm in Qatar and then Kuwait and Iraq on assignment and I was turning work down. I'm sitting in Kuwait thinking this is pretty cool – if I was in San Francisco I would have been broke. So by jumping off the cliff with a backpack of digital gear I ended up floating down having done well financially and also having made some great work."

The one question that we both conceded had to be asked was that it's one thing for an established photographer with a good reputation to embrace this brave new world, but what do you say to someone starting off? What's their point of departure? Kashi talked about one case of which he had personal knowledge.

"A great example right now that I'm intrigued to see how it evolves is Eric Grigorian who won the World Press Picture of the Year. He was a student of mine in London in 1998 as part of the Syracuse program. After that he graduated, went back to LA, lived with his family, made trips to Iran which is where he's from. All of a sudden he's won the World Press Picture of the Year, one of the largest accolades in the profession, but it's not like the phone's ringing off the hook with assignments. He told me he's just left for Iraq, but he's got no assignments. He's with [the agency] Polaris, so let's see what's going to happen. Here's a guy who made a decision ‘Well, I'll live with my family, go and make these trips to Iran because I'm very interested in exploring this place.' Most importantly he was making some wonderful pictures and he won this great award. Now his name is more on the map, but I think it's a reflection of where things are today that maybe ten years ago that same person would have been going with assignments to Iraq. Now it's ‘Great you won the World Press, buddy, good luck, go get ‘em.' Hopefully in two three months from now we'll find out he made some great stories and they were picked up."

As for his future, last November he and his wife formed their own Not-For-Profit called Talking Eyes Media (www.talkingeyesmedia.org) that they will use as a tool to finance projects that are outside of the interests of the traditional media. Their first grant came last December from the Nathan Cummings Foundation to do a book on uninsured Americans, Denied: The Crisis of America's Uninsured. The Nathan Cummings is primarily a health care oriented foundation that tries to advance awareness around health issues and health care. He says that he reason they were awarded the grant was as a direct result of the success of Aging in America. When NCF wanted to do something on uninsured people the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation advised them to approach Kashi and Winokur.

"Robert Wood Johnson gave us this money and we really came through for them with awards, the web site, the book, exhibitions. We proved to them that they didn't just throw their money at some folks who went and bought a new Lamborghini or paid their mortgage off."

He admits that even with all of the success that they've had and are having it's still a tough business to be in, and indeed it always has been. But for both of them these are exciting times to be living and working as professional witnesses to our developing society.

"When people who are so jaded and cynical say ‘Oh this kind of work doesn't mean anything' I say ‘Bullshit,' and ‘There's no power to the print media,' ‘Bullshit.' You can touch people in still pictures and words if it ‘s done right and it's done with heart and commitment, you can make an impact."

I sometimes think that photojournalism today is a bit like my mother buying a new bed at the age of 92. Often it doesn't make much sense to do something and the naysayers will give you all the reasons as to why you shouldn't, unless of course you really want to do it and then it seems as if it's the only logical thing to do. To misquote mum, "If you want to be a photojournalist you will be a photojournalist."

While we're on the subject of books, and because this is the brief period of the year when our good feelings towards our fellow citizens are such that we feel the need to express them through gifts, I hope that Santa has been doing lots of reps at the gym lately. He'll need all the muscle definition he has to deliver some of the tomes that have landed on my desk in the last few weeks. And good tomes they are. Some of the most powerful photography books that I've seen for a long while have poured out of the few publishing houses left still brave enough to produce them.

The problem publishers have with them is that most of them don't fit neatly into our preconceptions of the festive season, given that most of them are not only heavy in weight but also in content. When my book on war photographers came out last November it did so to be available for the holidays, although I'm not sure how many people actually want pictures of dead and maimed people before they eat a good lunch. On the other hand, since we've turned two ancient religious observances into orgies of self-indulgence, maybe that's exactly what we need in order to remember that for many Christmas and Hanukah or any other festivities are cruel jokes.

Wherever you're spending the holidays, and however desolate the circumstances in which you may find yourself, you're in the lap of luxury compared to anyone in Grozny. If you doubt my statement take a look at the pages of the magnificent book by Stanley Greene, Open Wound: Chechnya 1994 to 2003 published by Trolley. I was born during the Second World War in London, and as a child I certainly saw more than my share of ruined landscapes, but compared to this blasted land I was in the Garden of Eden. There is no way to express to you in words the power of this collection of pictures; you have to look at them for yourself.

So go to it and give the gift that keeps on giving. There's a lot to choose from; these are just some of my personal favorites, and as you browse through the many choices just remember that photojournalism is dead. Yeah, right!

Have fabulous holidays and a peaceful and productive 2004.

© Peter Howe

Contributing Editor

|

||||||

|

Write a Letter to the Editor

Join our Mailing List

© The Digital Journalist

|

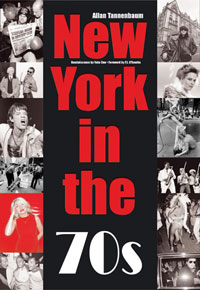

With Allan Tannenbaum's New York in the 70s: Soho Blues-A Personal Photographic Diary published by Feierabend you have a gift that you can safely give to your grandma, depending on how broadminded she is. Of course, having lived through the seventies myself I tend to forget that some of your grandmothers may actually be in the book. Tannenbaum, a talented and hardworking photographer for over thirty years, realized that he had a body of work from that decade that would make a book, and what a beautiful body it is. All the excitement and desperation, the madness and creativity, the fun and the fatalities of that extraordinary decade are there. If you learn nothing more from it you will discover the Keith Richards always looked as old and raddled as he does now.

With Allan Tannenbaum's New York in the 70s: Soho Blues-A Personal Photographic Diary published by Feierabend you have a gift that you can safely give to your grandma, depending on how broadminded she is. Of course, having lived through the seventies myself I tend to forget that some of your grandmothers may actually be in the book. Tannenbaum, a talented and hardworking photographer for over thirty years, realized that he had a body of work from that decade that would make a book, and what a beautiful body it is. All the excitement and desperation, the madness and creativity, the fun and the fatalities of that extraordinary decade are there. If you learn nothing more from it you will discover the Keith Richards always looked as old and raddled as he does now.