|

Images

January 2004

|

|

||||||

|

We are now just done with that time of year when editors decided the best books, film, theater, and journalism for 2003. I have been thinking particularly about pictures, mostly of war, but also how various images help shape different events. Specifically, I have been thinking of those images conceived and created through the discerning eye of the photographer and recorded on film, video and digital, not sketched or painted. However, never forget Bill Mauldin's drawings of Willy and Joe in World War II, and how their grit rivals most anything ever recorded on film. It seems enduring images of war are often not those of combat. Many that stay fixed in our minds have nothing to do with fighting. Sometimes war defines itself not in the photos of combat, but in the peripheral ones, sometimes defined by that wonderful euphemism, collateral. Nick Ut's photo of the girl in flames on the highway to Bien Hoa, Eddie Adams' photo of Loan executing a prisoner during Tet. Mathew Brady's shots of haggard Civil War soldiers, men in the endless trenches at Verdun in World War I, exhausted soldiers surviving the rigors of the Battle of the Bulge. Other sets of images which stay with me are those of refugees in flight, in Vietnam, Rwanda, Kosovo, wherever. Refugees fleeing for their lives moving on an endless treadmill with no end in sight may be one of the 20th Century's most cruel images. Then there are all those black body bags piled at Tan Son Nhut Airport and finally offloaded in Dover, Delaware on many a cold February day during all the years of the Vietnam War. More than ever, images we do not want any part of dominate our world. Interesting that there are almost never images of peace or tranquility that burn into our consciousness. The images that fill my mind are of war, violence, terror, hunger, and want. Rather than the war itself, the action and the fighting, the effects of war are the ones that stay in my mind.

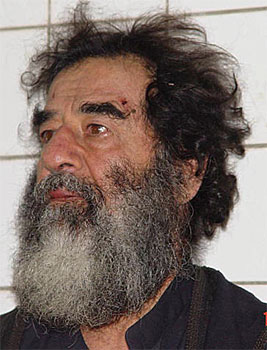

What will be the defining photo for this, the second Gulf war? Will it be heroic, a GI standing on a Humvee, silhouetted against a desert sun? Will it be GI's in the streets of any Iraqi city holding back a confused, sometime angry crowd of people? Will it be the eager face of a child in a classroom listening for the first time to a teacher free of fear? Will it be the capture of Saddam Hussein in manacles doing an international perp walk through his former domain? In time, will it be photos of American troops departing Iraq? Will it be American troops stringing barbed wire around a village to keep the bad people from doing damage and the good people from freedom? Will it be the funeral of an Iraqi child killed accidentally in an American counterattack to violence against them? Will it be hundreds of Iraqi's kneeling in prayer, their cloth-covered backs a colorful mosaic with a huge American tank hovering over them in the background? The contrast we see everyday from Iraq is tremendously bizarre and will continue until the war ends and the country is at peace. The possibilities are endless because there is an infinite variety of opportunity, planned and serendipitous, to get the one shot that will endure forever. At the war's start, after the endless run-up, we saw many pictures we thought defined the hostilities. Tanks and Bradley Fighting machines crossed open, desolate, endless desert. Guns blasted at everything in every direction. Sandstorms were frequent occurrences. Bombers destroyed all in their wake. At night tracers crossed the sky creating a curiously lovely light show. We witnessed the toppling of Saddam Hussein's statue. We saw President Bush's "Top Gun" arrival at sea. President Bush carrying a turkey in Baghdad. Then we had a picture that may become the war's most memorable.

Already many people, including media critics are expressing disgust with the frequent showing of Saddam Hussein in captivity. Too bad. We see his beard, full and matted, an extra long Q-tip probing the inside of his mouth, probably to test for DNA. The image is indelible and strong, unexpected for its simplicity, a tyrant in captivity without a shot fired. That is too good to be true. For now, for me no other picture best defines the war. Perhaps one, or even many, will later emerge. Until then, we have to await its birth. Time Magazine recently made its choice for Person of the Year, nominating The American Soldier, a noble, worthy gesture, a great idea, and deserving. But that issue's cover is a static photo of combat ready men, and it lacks heart. Perhaps the editors at Time tried to make it free of sensationalism, meaning a cover without action, without blood, without suffering. Soldiers showing strength and security are what soldiers should show. Only the cover does not work. It requires more honesty and yes, more muscle. We as a nation should not be ashamed to show we are powerful as well as just. Time's idea is fine, but the image is weak and not true to war, which, after all despite the many small successes, is what is still happening in Iraq, and Afghanistan. Recently there has been some justified barking that American's see too few images of death and dying out of Iraq, unlike what we saw, even in part, during the Vietnam War. This combination of the media's self censorship for reasons that are unclear, and the government's effort to sanitize the bloodshed, for reasons that are quite clear, gets no applause from me. War is a tough ticket, but without seeing it, and thus recognizing how destructive it is, we end up relying on Hollywood for truths that are better served in real time by real events. Everyone has an image or set of images for everything that resonates with them. To have real and lasting meaning, no image should be doctrinaire or dogmatic. Background, upbringing, and ultimately experience make one image more affecting than another. In some cases as journalists, we are present at the creation of a significant image. Oftentimes, editors in how they play a photo, define the image for us. Lately more newspapers, and probably news broadcasts too, are starting to show pictures of soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Will these be the most memorable images from these two concurrent, ongoing wars? I am still looking for the defining image for Iraq. If anyone has a nominee for the best image, the most gripping or most powerful, please send me a note, and I'll publish the results as part of my next column. Perhaps years from now, we will find that photo among the many shot. Or we may learn as we look back that the significant photo of the war is yet to come.

© Ron Steinman

|

|||||||

|

Write a Letter to the Editor

Join our Mailing List

© The Digital Journalist

|