PROLOGUE

I was twelve years old when the radio announced that the Allies had

launched the long awaited invasion of Europe that would ultimately

lead to victory and the end of World War II. That day was June 6,

1944 and would come to be known as D-Day.

This June will be the 60th anniversary of that historic event.

I beg your indulgence as I begin the story, about one of the greatest

assignments of my long career as a newspaper photographer.

D-DAY REVISITED

By Dick Kraus

Newsday

Staff Photographer (retired)

I always had difficulty sleeping on planes and this long flight proved

no different. We had left JFK Airport around midnight on a non-stop

flight that would take us to Frankfurt, Germany. I had the window

seat. Dozing in the seat next to me was Jim Kindall, the reporter

with whom I was working.

I turned and gazed out of the window. We had been flying for hours.

For exactly how long, I had no clue. I had lost track of time as

we passed through one time zone after another while we sped eastward

to greet a new sunrise. As I looked down through the stygian night,

expecting to see nothing more than the darkness that was the North

Atlantic, I was surprised to see lights far below. At first I thought

they might be the navigation lights of some fleet of fishing trawlers

working the ocean far beneath me. But, I noticed that there were

regular patterns to the lights and assumed that we must be over land

now, and passing some small villages on the coast of Great Britain.

That would mean that we would be landing in an hour or so.

Six weeks earlier, I had returned to the office after covering several

forgettable, mundane assignments. Sandy, the Photo Department Den

Mother/Secretary, stopped by the door of the color processing room

and said, “Jim wants to see you in his office as soon as you

have a chance.”

Hmmm. What could that be about? Jim had been the Chief Photo Editor

at Newsday for a number of years. He and I had different opinions

on newspaper photography and our working relationship could be said

to have been cordial but nothing more. I was obviously not his first

choice among the staff of some thirty-odd photographers to be awarded

any plum assignments. But, he was the head of the department, so

I got my film started in the processor and went to see him.

His back was toward me as he worked at his computer. I knocked on

the frame of his open door. “You wanted to see me, Jim?”

“

Oh, yes Dick. Come on in.” He turned to face me. “I have

a project that I want you to work on.”

Oh, Jeez. What could this be about? Projects were normally

sought after assignments that usually went to his preferred staffers.

If he were giving one to me, it would probably be something that

required an obscene amount of headshots. Many of our projects were

all about headshots. They were usually investigative pieces that

involved making head shots of the people involved. And, since so

many of them were reluctant to be photographed, it would mean staking

them out and playing paparazzi. I hated that. But, Jim invited me

to sit down and I listened as he explained what this project entailed.

Newsday was planning a huge special section to commemorate the 50th

Anniversary of D-Day, which would occur in less than a year. It was

then early November 1993 and he wanted me to collaborate with James

Kindall, one of Newsday’s top feature writers. Kindall would

be interviewing American Veterans who survived the landings and the

war, and documenting their recollections of that historic event.

Mostly we would interview vets who lived on Long Island, but some

would require a bit of travel.

Oh crap!! Just as I thought. Headshots.

He went on. Kindall and I would travel to Germany to interview German

veterans who had fought against our troops and attempt to prevent

them from landing in Normandy.

Hold on a second. Did he say Germany? Was I going to Germany to do

this? Or would he say that I was only doing the local angle and they

would get the wire services to shoot the German part of the story?

No, he was really saying that not only would I go to Germany, but

I would travel with Kindall to France where we would talk with survivors

of the French Resistance and also photograph the locations in Normandy

where those Allied landings took place.

We were to spend a week in Germany and then a week in Normandy. After

that, there would be more work locally. As Kindall wrote his story,

we would get together and wed the art with the words. I was told

that I would play a major role in putting out this special section.

My boss said that I would collaborate with the Art Director who was

to do the layout. Plus, Kindall and I would return to France just

prior to the actual D-Day Anniversary to file daily stories about

the preparations as well as the ceremonies on June 6th. All of this

was unprecedented and I couldn’t believe that I had been chosen

to do this great project.

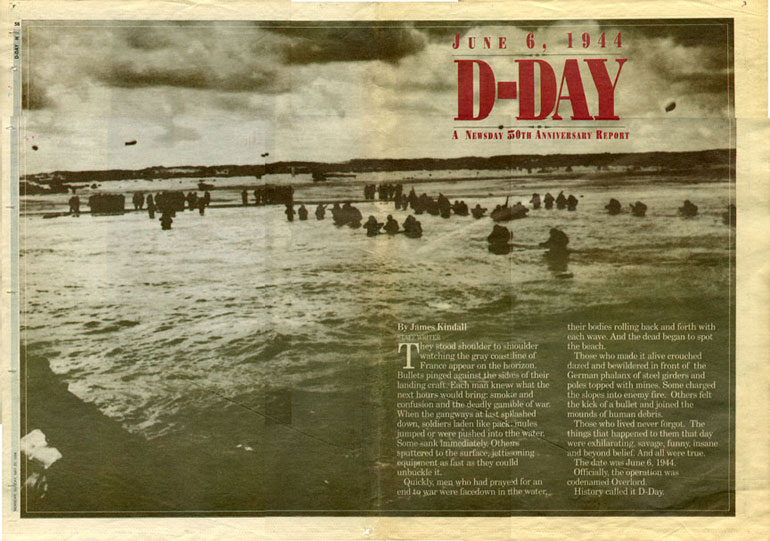

© Newsday

This is the wrap around front

and back page of the special D-Day issue put out by

Newsday to commemorate the 50th Anniversary. The photo

was from the archives and was shot on June 6, 1944

as American

troops waded ashore in Normandy. My copy is

a bit faded and yellowed with age. |

|

As soon as

I finished with The Chief Photo Editor, I went out to the Newsroom

to find Jim Kindall. I knew of him. I had read some

of his stuff. But, I had never met him. He did features and I did

mostly news. I asked around the room and was directed to Kindall’s

desk. I found him working his way through piles of paper on his

desk, which also contained open maps of Germany and France. Jim

was a good-looking

young man who had an intensity about him, which indicated to me

that he took his work seriously. That was encouraging and when

I introduced

myself, he greeted me warmly and said that he was familiar with

my work. I knew that he would be a pleasure to work with.

Kindall told me that he had spent the day on the phone to Germany,

trying to locate several of the German veterans whose names he

had been given. Some were deceased but there were several with

whom he

had made contact and he was able to set up interviews in the next

couple of weeks. He had marked their hometowns on the map and now

we made plans on how we would proceed once we got to Germany.

Our decision was to fly to Frankfurt on November 16th. We would

get a Eurail Pass and would take trains around Germany to get to

our

various interviews. This would take a week and then we would take

a train to Caen, France, which was the provincial capitol of Normandy,

and we would operate out of that city as we covered the battlefields

and the French interviews.

|

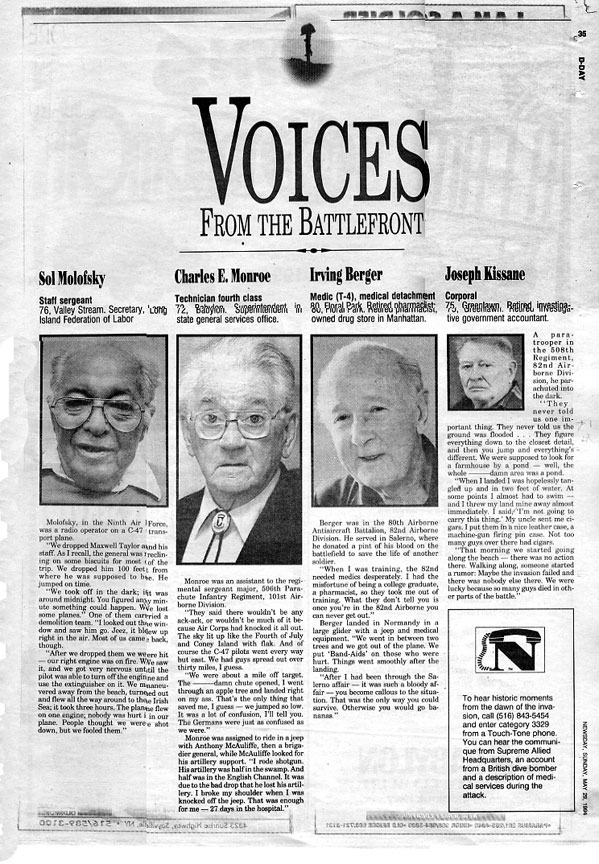

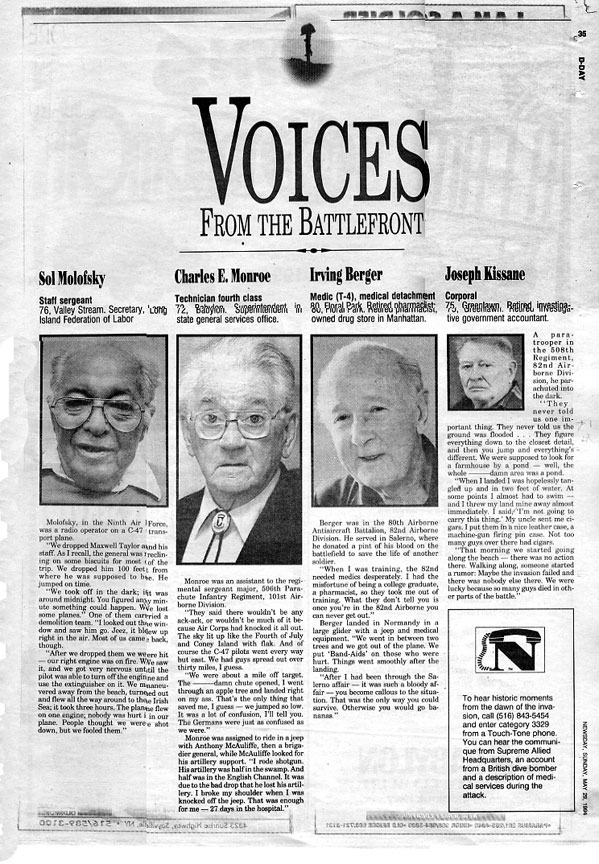

Before

leaving for Europe, though, I would start photographing some

of the local American veterans. Kindall was to concentrate

his efforts on the main stories. Other reporters would do the

interviews with the local vets, some of whom would be categorized

under the heading of “Voices From The Battlefront.” I

would photograph most of them. Other members of the photo staff

would make those whom I couldn’t do because of time constraints. |

Kindall did

the first interview because it was a major part of the main story.

The noted author, Cornelius Ryan, had documented

this

particular incident in his book, “The Longest Day,” which

chronicled the D-Day invasion. It was later made into an epic

movie. This story pertained to a specially trained unit of the

US Army Rangers,

which was to land at the base of the steep cliffs that ran down

into the water at a place called Pointe du Hoc. The Rangers were

to shoot

rocket propelled ropes with grappling hooks attached, to the

top of the cliffs and then they would climb the ropes, all the

while

taking heavy fire from the German troops firing down on them

from the heights. Their mission was to secure the cliffs and

destroy the

battery of German 155 mm coastal guns that American Intelligence

had determined to be there. Those guns could play havoc on the

ships and landing craft as they discharged the troops on the

beaches below.

In his book, Ryan wrote that the mission was a failure that cost

many American lives, because when the Rangers finally got to

the top, they found that the 155’s in their emplacements were phonies.

The Americans had suffered many dead, only to find that the critical

guns weren’t guns at all.

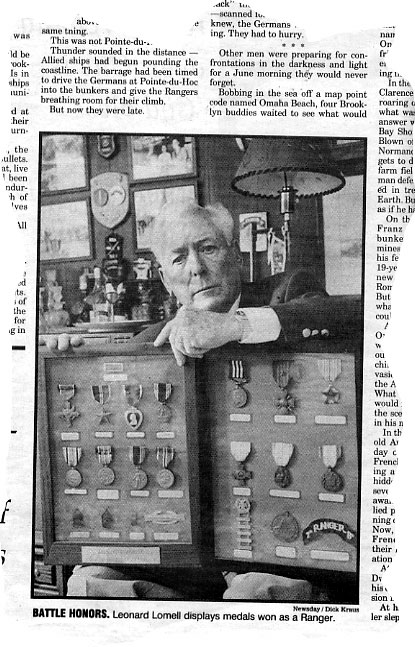

Jim Kindall and I drove to New Jersey to interview one of the survivors

of that raid. Leonard Lomell was a highly decorated sergeant who

remembers the battle quite well. I photographed him with his medals

and as he spoke of that day, his voice was tinged with resentment

when Ryan’s account of that battle in “The Longest

Day” was brought up.

Lomell transported

us with him into the Hell of that furious raid as he detailed all

that had transpired. He talked of the brave comrades who fell under

the fusillade of bullets that rained down on them as they stepped

from their landing craft and ran for the temporary shelter afforded

by the overhanging cliff. He spoke of the difficulty of firing

those coils of rocket-propelled ropes to the top, many of which

bounced off and fell back onto the beach below. And then, of the

arduous hand over hand climb to the top, watching friends being

blasted from the ropes by enemy gunfire and falling hundreds of

feet into the ocean.

Len Lomell

made it to the top with a flesh wound in his side, and along with

a handful of brave survivors, secured the area. That’s when

he made the horrible discovery that the guns were phonies.

It is here that Lomell departs

from the account in the book. His voice rose as he tells us that Cornelius

Ryan

neglected to follow up on the Rangers’ actions after getting to the top

of Pointe du Hoc. It was then that Lomell and another G.I. went on a scouting

mission. After crawling on their bellies around one hedgerow after another

they came upon the real 155mm guns in a field about 200 yards further inland

from

the top of the cliff where they had landed. The two men couldn’t believe

their luck. Not only had they quickly located the reason for their mission,

but the guns were unmanned and unguarded. A few hundred yards further away

were the

German gunners. They were grouped around an officer and were apparently being

briefed about the Allied Invasion. They were oblivious to the Americans in

their midst.

Lomell crept to the

German guns and dropped thermite grenades in the gears of their

tracking mechanisms. The grenades were relatively silent and

went unnoticed by the Germans. The thermite burned at extremely

high temperatures and melted and fused the gears rendering the

guns, as Lomell put it, into huge paperweights, since they could

no longer be turned to bear on any targets. |

|

At least

the proud veteran was able to clear the record on the efficacy

of the raid at Pointe du Hoc as far as the readers

of Newsday were

concerned.

newspix@optonline.net