|

→ June 2004 Contents → Avedon at Work → Photo Gallery

|

|

||||

|

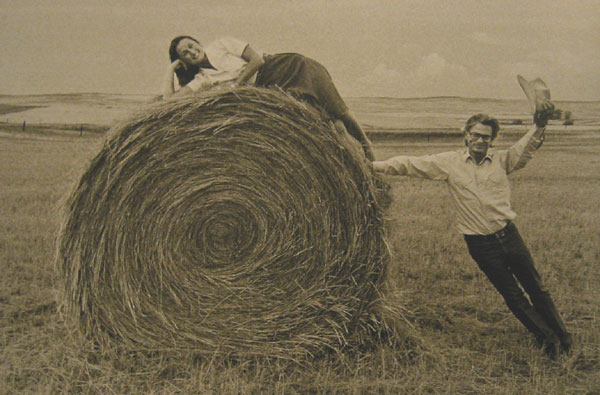

A generation has passed since Richard Avedon took his first photographs in the summer of 1979 for the exhibition and book, In the American West. At the time, his portraits contradicted the most recognized work by the most honored photographers of the West. Avedon's West was a shock. Where were the lush, pristine landscapes of Carlton Watkins or Ansel Adams? Where were the cowboys of Life magazine's Toni Frisell and Leonard McCombe? And certainly Avedon's Native Americans looked nothing like the Indians Edward Curtis photographed in war-bonnets and porcupine quills. In 1985, when the work was complete, not one museum in New York City would agree to an exhibition. "Avedon's West," declared John Szarkowski, then the Museum of Modern Art's preeminent curator of photography, "is not the West as I know it." Although critical acclaim mattered to Avedon, he understood where he was headed and who his subjects should be far better than the critics ever could. He had purposely titled his book In the American West, not The American West. These portraits were an extension of his previous work: portraits of his father, of Jean Renoir, Marilyn Monroe, and Francis Bacon, photographs of patients from the East Louisiana State Hospital and, going back to the 1940's, portraits of street performers in Italy. When you look at his work as a whole, you can see that the portraits overlap and relate to one another. These portraits made in the West became part of a continuous and developing whole. They reflect Avedon's single-minded pursuit of his own vision, his exploration of the ambiguity and absurdity of the human situation. They were never meant to be a representative selection of Westerners. He said, "These are people without a voice. I wanted to learn what we had in common. Certain things are shared by everyone. I'm interested in connections between people of remote experience, in unexpected similarities. Paradox, irony, contradiction - those interest me in a photograph." The challenge for Avedon was to find a connection to people with whom he was unfamiliar, people who mined coal, worked in slaughter houses, or waitressed at roadside cafes. "In the West," Avedon said, "I worked with very, very strong feelings. I photographed what I feared: aging, death, and the despair of living," On the road, Dick often had severe headaches. He would go back to the motel, pull the shades down, take some medicine, and wait until the headaches went away. In retrospect he said, "Those were important headaches. The work was not thought out. I was expressing my feelings in the only way I could, by taking pictures. It came from within, from a desire to make the portraits crucial. When I try to put it into words, it's less than the pictures will ever be." In Butte, Montana, Dick photographed an unemployed copper miner, Roy Gustavson and his wife Judy. I remember he looked in wonder at them. It was 1983, and eighteen hundred miners had just been laid off. Seven hundred houses were up for sale. The huge Berkley open-pit mine shut down. The value of copper had dropped. The selling price of 75 cents per pound didn't cover the cost - a dollar a pound - to get the ore out of the ground. "Butte couldn't be worse if a cyclone hit it," one miner told us. What happens to people when they lose their work? Where do they go when there's nowhere to turn? These were the questions the men and women in the portraits faced. Luck running out formed the narrative behind many of the photographs. Avedon chose certain people because they seemed to be asking, on a deep level, some of the questions he was asking. He saw in them an expression of what he himself felt. I'm sure a great many people he photographed had their own expectations for the photographs and had no idea what he was doing or why he chose them. They could not anticipate what his pictures of them would look like. By conventional terms, many of the portraits were unflattering. Critics attacked him for exploiting people who were unaware of his intentions. In his forward to In the American West, he said, "A portrait photographer depends upon another person to complete his picture. The subject imagined, which in a sense is me, must be discovered in someone willing to become implicated in a fiction he cannot possibly know about. My concerns are not his. We have separate ambitions for the image. His need to plead his case probably goes as deep as my need to plead mine, but the control is with me." I assisted Richard Avedon for six years and watched a man who had spent almost forty years looking and judging, selecting and inventing, transforming his subjects into metaphors of his own meaning. He looked for inspiration everywhere. Work had become the source of his energy and he worked constantly often to exhaustion. Everything else in his life was secondary. I saw what was given up, what was gained and I learned just how imaginative, unrelenting and brave an artist must be. In the end Richard Avedon photographed 752 people, using 17,000 sheets of film. We worked in 17 states and 189 towns. From this collection he chose 123 photographs for the exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum. Mitch Wilder died on April 1, 1979 of leukemia after having been diagnosed only six weeks earlier. He never saw a photograph from the western project. The museum went forward with the project. In the end, the portraits were printed life-size and slightly larger to provoke a confrontation between the viewer and the subject. In life, you often can't really look at someone the way you would like to, you can't stare. It would be embarrassing. In movies and on television people move, but with these large portraits, you could stand in front of them and look for as long as you wanted. And the people looked back. There was an exchange. In that scale the photographs took on a life of their own. Dick said, "I know that sounds like fake modesty, or some Zen thing, but really I feel that these people are so powerful. When you look, really look, they say such varied things with their faces and their bodies. It's almost as if there was no photographer. I'm out of it. I feel the work now belongs to the people themselves. It's between them and you." |

||||