|

→ August 2004 Contents → Feature

|

The Death of a Famous Unknown

August 2004

|

|

|||||||||

|

One of Henri Cartier-Bresson's favorite quotations was from the French painter Degas, who declared that it was "wonderful to be famous as long as you remain unknown." That Cartier-Bresson was famous is apparent from the length and position of the many obituaries that have appeared since his death at the age of 95 on Aug. 3 at his house in the Luberon region of southeastern France. The New York Times ran a 3,400-word version that started at length on the front page; BBC.com had no less than five articles on him, plus a page on which readers could post their personal tributes; regional newspapers across the United States, including the San Jose Mercury News, The Indianapolis Star, the Seattle Post Intelligencer and The Miami Herald carried extensive obits; Google News, the section of that service which searches for news-related items, turned up a total of 367 articles pertaining to his death.

To the French he was a revered national treasure, and yet I doubt that many would have recognized him had they seen him walking in the gardens of the Tuileries that his apartment overlooked, an apartment that has not a single photograph on the walls. The timeline of his life is well known, and does not need to be repeated here, but there are turning points within it that are important. He was trained as a painter, like many other photographers, including his friend Walker Evans, and the biggest influence on his early art was that of the Surrealists. It is the influence of this movement that gave so much of his work its distinctive character, especially those photographs taken during the 1930s and '40s. Equally important was his interest in Eastern religion, especially Buddhism, which emphasized the importance of the inner person as opposed to the outer shell. The way that this affected his photography is revealed in a much-quoted comment of his: "In whatever one does, there must be a relationship between the eye and the heart. One must come to one's subject in a pure spirit. One must be strict with oneself. There must be time for contemplation, for reflection about the world and the people about one. If one photographs people, it is their inner look that must be revealed."

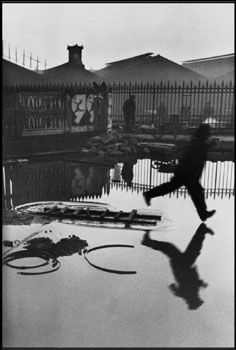

The desire to be inconspicuous led him to cover up the shinier parts of his Leica with black tape to make it less noticeable. There is a story, which is probably apocryphal, that he was working one day with his taped camera at a time when black bodies were readily available. Someone who was watching him work looked at him and said, "Ah, the poor man's Cartier-Bresson." In 1952 he published his first book, entitled "Images à la Sauvette," the English edition of which was called "The Decisive Moment." This title was from his preface in which he quoted the 17th-century writer, Cardinal de Retz: "There is nothing in this world that does not have its decisive moment" and the phrase has been associated with his photography ever since. He went on to amplify this idea in the elaborate phrase: "the simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second of the significance of an event, as well as the precise organization of forms that give that event its proper expression." I much prefer the description that he used in an interview in 2003 with Susan Stamberg for National Public Radio. He was talking about the photograph that most affected his career, that of three African boys running into the waters of Lake Tanganyika, taken in 1930 by the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkacsi. He described the photograph as perfection, and said that it "made me suddenly realize that photography could reach eternity through the moment." He was always aware of the intrusive nature of photography, that in some ways it is a violation of the subject, that it must be tempered with humanity so as not to become a brutal act. If you look through the 40 pages of his photography that are on the Magnum Web site, and I strongly recommend that you do, his empathy for his fellow human beings and the awesome chaos of their existence comes shining through.

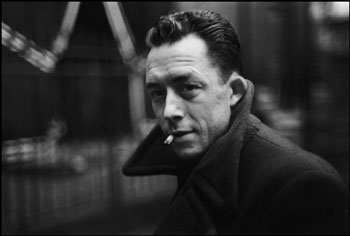

He photographed many famous people, but in every page of thumbnails it is hard to distinguish the distinguished from the ordinary: Henri Matisse looks very much like any other old man, his doves taking up more space in the picture than he; Albert Camus could have been anyone that happened to be walking down the street at the moment. Cartier-Bresson photographed all over the world and yet he could find the universality of human experience that links the streets of Paris with those of Beijing or Jakarta. In the NPR interview quoted above, Martine Franck expresses her admiration for and amazement of her husband's ability to be in the right place at the right time: "I think Henri had an innate intuition of what was going on in the world and what was important. I mean, you were in India when Gandhi was assassinated. You were in China when the communists arrived... You were in Russia at the right time." But his timing went beyond mere location; his career straddled, and indeed defined, the golden age of photojournalism. It is difficult for those who are his successors, struggling to make a marginal living in a marginal market, to remember that for many years and for many people the predominant source of information was the magazines that struggle for existence today. He also knew when to get out, leaving Magnum in 1966, and ceasing to be a photographer in 1975, thus avoiding the painful experiences that photojournalism has suffered since then, although remaining engaged with his former profession and its practitioners. He wrote a spirited and defiant letter in support of the French Sygma photographers when they went on strike against Corbis in 2002. Along with the extraordinary eye that produced the legacy of his body of work, the thing that I shall miss most about HC-B is his iconoclastic and often acerbic pronunciations on our craft, through which he reminds us that we should take photography seriously, but not ourselves. He described photography as "a marvelous profession while it remains a modest one." On another occasion he declared it to be "instant drawing." But he also told us that "photography is a matter of putting your brain, your eye and your heart in the same line of sight." So, in a way, he leaves two legacies: to the world he leaves a compelling, heartwarming and sometimes heart-wrenching view of the 20th century; to those of us who share his modest profession he leaves wisdom to guide and inspire. So the next time that you lift your camera to your eye, remember the words of the master when he said: "With the one eye that is closed, one looks within; with the other eye that is open, one looks without."

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to August 2004 Contents |

|