|

→ November 2004 Contents → Feature

|

Beyond Our Horizons

November 2004

|

|

|||||||||

|

If I had a dollar for every time I've either said or written the word photojournalist in the last 30 years, a brand new Maserati Quattroporto would be standing right now outside my much larger house. And yet even at this late stage of the game I was trying to work out exactly what the definition of the word should be. Webster's is very clear in its explanation: a journalist who presents a story primarily through the use of photographs. Dirck Halstead has put forward a customized clarification especially for The Digital Journalist: anything that is shot, in still or video, that has communication as its purpose. Mine would be closer to any poor schmuck who thinks he or she can make a difference to the world through the use of a camera.

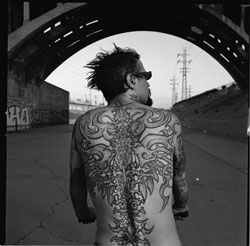

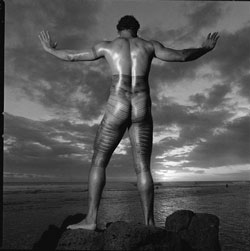

Given the nature of their subject matter, are these photographs journalism or anthropology? Chris thinks that in a pure sense they're neither. "I dance over into the art world because I'm creating and pre-visualizing images," he told me. "I'm constructing an image in which to illustrate a particular tattoo or body marking. So it's not pure photojournalism, and also, as far as ethnographic documentation goes, I'm not doing pure anthropology. I'm trying to create images in which people get the sense of the spirit of the place, spirit of the person, and that evokes a sense of mystery."

The idea for the seven-year project came out of the work that he did in New Guinea, and which provided the material for the book "Where Masks Still Dance." The motivation for the project was Chris' career-long commitment to drawing lines of understanding between our culture and others that are beyond our horizons, and which we often find both strange and scary. This involves searching for the commonality between disparate societies, and the desire to embellish the human body is an activity that links the inhabitants of Polynesia with the gangs of East L.A. or the chic of the East Village.

He went on to say that in traditional cultures, although the body is often considered sacred it is also regarded as a canvas upon which you impose your identity, and you are not considered complete until you've been tattooed, or if your skin is dark, scarified. These markings are a rite of passage from childhood to adulthood, adulthood to warriorhood, or, if you're a woman, from virginity to eligibility for marriage. The reason that so many people in the west, especially the young, have taken to marking their bodies, Chris believes, is because of the devaluation in our society of similar guideposts.

"I think what's going on in the west is a real fascination with wanting to have an identity in a world that's spinning out of control, where many people are feeling frustrated with our traditional spiritual belief systems; they're looking for new ones; they're exploring; they're appropriating other cultures. It's a quest, it's a plea, and it's also an affirmation of belonging, whether it's to a gang in East L.A. or a basketball team. It's an expression of identity that makes one feel, through that painful initiation, like you belong to a special group."

Chris's work is remarkable in three ways. First of all the photographs themselves are elegant evocations that take the viewer to places they would not normally go and show them sights they would not normally see. I suppose the most extreme example of this is the fact that few of us would see the tattoos on the back of the mistress of the head of the Ikuza, and live to tell the tale. The Ikuza are the Japanese equivalents of the Sopranos, only better dressed. How Chris got to her is in itself an interesting tale, and was the result of one of the Ikuza's more unpleasant practices. If a member transgresses their rules in any way they are forced to cut off their own pinkie fingers as a punishment. Chris takes up the story:

"I was looking through a tattoo magazine and I noticed this Japanese tattoo artist who was missing his pinkie and I knew, bingo, he was probably associated with the Ikuza. I contacted him, and had my assistant fly over for a series of meetings. It took about two or three weeks to put everything together but I finally got permission to work within the Ikuza and I spent a long time photographing them. Then I saw a picture of this woman, who is stunningly beautiful, and so we arranged for a photo session with her. It was a very tense situation with all sorts of bodyguards, and the head of the Ikuza was there, but I got the photographs."

The second way in which I find Chris's approach to his work encouraging is the way that he finances it, and it runs along the same lines as all of the photographers whose projects I have extolled in The Digital Journalist. Apart from being a regular contributor to the lottery (which as you know is a tax on people who don't understand math), he initiated the project through piggybacking on other assignments, dipping into his life savings - he told his wife that the book is their equivalent of a vacation home - and getting mini-grants until there was enough traction for magazines such as Condé Nast Traveler or Outside magazine to give him stories to do on associated topics. This was not a cheap project to complete. The people he was photographing were mostly way off Jet Blue's route map, and he had to sometimes go to these remote places two or three times. It is unlikely that he will recoup his expenses even if the book is wildly successful, but he describes it as "an assignment from within" and recognizes that it and other similar projects have allowed him to find his own voice photographically.

The final part of my trilogy of admiration is that having found a voice, Chris also found a theme, and one to which he is passionately committed - that of increasing our understanding of and sympathy for our distant cousins with whom we share this planet, but whose needs and rights we so often sorely misjudge. If ever there was a message that needed to be heeded in the era of the born-again crusader it is the one that he so eloquently and powerfully communicates with his camera, and one that he believes will benefit all of us: "I think the trend in conservation these days is to help preserve traditional cultures, because in this way you help preserve the land. The culture that lives on the land inherently wants to maintain that land to survive, and so I think we're shifting into a new paradigm in the 21st century of sustaining culture, of being aware of culture."

One of the difficulties he sees in his message being effective is that we all tend to think of our group as being the center of the universe, whether we are American or Bedouin, but as a self-declared romantic and optimist, we, the story tellers of our tribe, have to keep adding our few grains of sand until there is a beachhead. Although he firmly believes in Peter Matthiessen's dictum that anyone you meet who wants to change the world is both naïve and dangerous, he also knows that photographers can be effective by merely laying out the evidence, as happened when he and many other photographers went to Somalia to cover the famine in 1992. There is a distinction between changing the world and making a difference to it.

For Chris it's now time to start another chapter in his life's work. He and his wife will acknowledge the completion of this project by going to New Zealand this Christmas to do a lecture, but also to get tattooed with Polynesian armbands. He knew that he had finished "Ancient Marks" when he went to a tattoo convention in New York in February of this year: "There were some pretty wild looking characters, Harley Davidson bikers and all the bizarre urban tattooing you see, and as I'm walking down these hallways they're going, 'Hey Chris, how's the project going?' It's at that point that you realize it's time to move on, if I'm on a first-name basis with these guys."

"Ancient Marks" will be available in mid-November and the purchase price of $85 will include a CD by Anouchka Shankar of music written specially for the book. Custom prints will also be available, details of which can be found on the Web site www.ancientmarks.com, along with other information about the project.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to November 2004 Contents

|

|