|

→ December 2004 Contents → Purple Hearts → Feature Presentation

|

Disposable Heroes

December 2004

|

|

||||||

|

How often have you heard people complain that their words were quoted out of context? This is a rhetorical question - I don't actually want you to tell me, I just want you to think about it. Something else to think about is how many times you've heard someone complain that a photograph was taken out of context; it's probably far fewer. As photographers, I think that we would like to believe that a photograph is so powerful a form of communication that it needs no context, but can convey an absolute truth single-handedly. This is probably the reason that photographers are so reluctant to write captions, although I suspect that laziness and literacy limitations may play their parts as well. But when you really think about it we can all come up with instances where a photograph that we took was used in a context that we didn't intend, with the result that its meaning was altered.

There have been a couple of articles in The New York Times recently in which context and photography were important, the first an op-ed piece dealing with the subject, and the second a report on the recent fighting in Fallujah which provided examples of the way that the context into which photographs are placed can enhance their power. The op-ed piece, by the Academy Award-winning documentary film director Errol Morris, discusses the effect of the images coming out of Iraq - in particular the videotape of a Marine shooting an unarmed and defenseless insurgent. Morris makes an interesting point, in that he believes that we see what we want to see and suppress that which we don't. He says, "Unhappily, an unerring fact of human nature is that we habitually reject the evidence of our own senses. If we want to believe something, then we often find a way to do so regardless of evidence to the contrary. Believing is seeing and not the other way around."

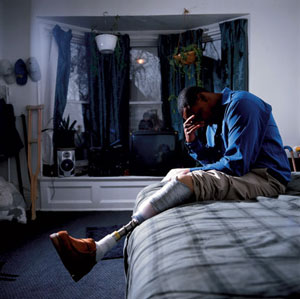

It is a similar interaction that gives Nina Berman's book, Purple Hearts: Back from Iraq, its strength, a force that delivers a punch to your emotional solar plexus when you read it. The chemistry here is slightly different, because it is not only the combination of images and text that is so powerful, but also the dynamic that often occurs between the observer and the participant. Berman photographed soldiers seriously wounded in Iraq when they returned to this country, mostly in their homes, but also at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. The accompanying text, however, is comprised of the words of the soldiers themselves, faithfully transcribed from interviews that the author did with them. Their voices are sometimes hauntingly surreal, the result of brain damage and shock, with relatives or friends trying to explain what the jumble of words means.

Nina didn't start out with the intention of producing a book, but simply wanted to satisfy the urge that drives all good journalists - curiosity. She kept on hearing reports from Iraq that a certain number of soldiers were wounded in actions that were taking place around that country, but realized that she was seeing no images of the them at all. Furthermore, she could find no listings of the wounded from the Department of Defense or any other source. The other thing that she couldn't find in the beginning was any interest in the story from magazines or other publications. So she set out by herself to track down likely subjects, using the modern journalist's best friend, Google, as a starting point. She described her method in a recent interview: "I would plug certain words like amputee, wounded, arm, brain damage, soldier comes home, and I would find local newspaper stories, and try and figure out if the soldier was probably back from hospital by then. I would also look in the stories for whatever names would be involved, sometimes a politician, sometimes a bank, sometimes a friend of the family, or I'd call the local newspaper reporter, anything to get a phone number for the family." This detective work, plus the permission from Newsweek to let her use their name, got her the access she needed to get started.

Her motivation for photographing some severely damaged people came from a sense of responsibility that she felt the mainstream media had abrogated at that point. She explains, "I felt a responsibility to show the other side and so in the most basic way it's just, 'Okay, look at this guy. This is what happens in war. It's not this clean, easy thing; it's not a bloodless enterprise. There are casualties.' I thought that the American public would only take this feeling to heart if they saw American soldiers; if they saw Iraqi civilians wounded I don't think they'd really care."

As both the war and the story progressed she did manage to pick up a one-day assignment from Time, which was the only way that she could get into Walter Reed, and she believes that now even with the influence of that magazine behind her it would be much more difficult if not impossible to get access.

This level of acceptance of mutilation and its consequences is disturbing until you realize, as Nina did, that many of them are still in shock, and some are still heavily sedated on painkillers. It is also unrealistic to expect men and women whose lives have been dramatically changed by traumatic injury to suddenly believe that the cause for which they thought they were fighting was flawed.

As you read the book you realize that although the anger for the most part is missing, there is an awful sense of loneliness. The thing that shocked me was the way that the military seems to dump those who have given the most, providing basic medical treatment, but no counseling and no preparation for the difficult lives that they will have to live from now on. The photographs reflect this, and Nina readily acknowledges this, "They're not great pictures, they're not graphic in terms of the injuries, but they're incredibly lonely, and this is something I want to communicate. These are not images of glorified heroes." She found photographing many of them very difficult. The first two portraits she took were of the blinded soldiers, which she did on consecutive days, and she found the experience harrowing: "The first soldier was completely blind, no optic nerve, nothing left, and I photographed it with a Hasselblad, which makes a lot of noise. Every time I went to take a picture he would flinch, and I felt a tremendous amount of power that I didn't want."

The project became a book when Gigi Gianuzzi of Trolley Books saw the photographs and insisted that he and Berman shelve the book they were already working on in order to rush this one out. Both agreed that it would be more effective if it could be part of the discussion of the war as it progressed, rather than a reflection on its aftermath. In the amazingly short period of two months, Nina located, interviewed and photographed 10 more soldiers, and laid the entire book out in two days. Although she admits that there are one or two things she would have done differently with more time, these perceived deficiencies are more than made up for by the relevance that timely publication has given it.

Even so, the book is really a starting point for Nina, rather than a completion. A soldier advocacy group called Wounded Warrior Project who had seen some of the images that had been published in Mother Jones contacted her and asked if they could use them on their Web site, woundedwarriorproject.org. The organization raised close to $100,000 as the result of Nina's permission to use them for free, and as payback to her the group built her own Web site, which they also maintain; the address is purpleheartsbook.com.

Berman believes that this was the smartest move that she made with the project, and says about it, "This to me is a model for other photographers. There are many photographers that do socially relevant stories, and they don't know how to move the story beyond maybe a photo essay in Time or Newsweek. If they were to find a non-profit organization that's just as interested as the photographer is, they can then say, 'Hey, I'm going to give you my pictures. See what you do with them; see if this helps your group.' The Wounded Warrior Project told me, 'Nina, before your pictures we were just a Web site with words.' It's a way to take your pictures beyond the magazine format, which to me can still be powerful, but it's not nearly as powerful as it once was."

Taking the pictures beyond either magazines or the book is important to her because she feels there is a need for the wider public to see the photographs and read the stories. To this end she has produced a short video, goes on speaking tours (sometimes in the company of one of the soldiers) and visits high schools. Her aim is to counteract what she feels is the unrealistic view of military life and warfare as presented by recruiters and television commercials. She tries to counterbalance their often-glamorous presentation in the same locations where recruiters look for likely candidates. One of the things that she learned while working with her wounded subjects was that too often young people, especially poor young people, sign up for the military out of desperation with their circumstances, and with little understanding of the full implications of the commitment. However, she has deliberately left her own political opinions out of her activities on this subject. She did this because she did not want the book to appear propagandistic, and felt that by using the exact words of the soldiers she would allow the reader to come to their own conclusions. In this she seems to have been at least partially successful. The lead reader review of the book on Amazon is headlined: "Don't be deceived; this book is NOT political." It goes on to say: "The only political issue raised by this book is whether or not we take care of these fine young Americans who've given a part of themselves for their country. We cannot throw this generation of war veterans to the wolves as we did their fathers and grandfathers 30 years ago. I am the mother of an American soldier, and I would like to thank Nina Berman for her book. Everyone should read it."

I can think of nothing else to add.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

|||||||

Back to December 2004 Contents

|

|