|

→ January 2005 Contents → Feature

|

Two From China

January 2005

|

||||||

|

Chronicling the dramatic changes occurring in China is no easy task for a photographer. The difficulty lies not in any shortage of photographic opportunities but rather in the choices a photographer must make - what to photograph and how to photograph it. As the director of Redux Pictures, I have the pleasure of working with two extraordinary talents who have been documenting China in very different ways over the past decade, Mark Leong and James Whitlow Delano. Two recently published books, Empire: Impressions from China by Delano and China Obscura by Leong, are compelling examples of their unique talents.

If Mark Leong is a realist then James Whitlow Delano is a romantic. His duotone photographs of contemporary China evince a poet's eye - dreamy, impressionistic, subtle, often melancholic. Looking at them, one can sense the animating spirit of the culture, the continuum between past and present in the everyday activities of this changing China. His photographs portray the ironies and contradictions of 20th-century China - a photo of twins born during the era of the one-child policy, Christmas-style lights in front of a silhouetted teahouse. One could guess at the date and be wrong by 50 years were it not for the details. The duotone prints themselves contribute to the sense of timelessness. Describing his working method, James says, "I must pass by quickly and quietly in order to capture the ‘out of the corner of my eye' immediacy that I seek before I disturb the scene." Indeed, the "corner of his eye" is, for us, a very large lens. Both photographers consciously focus on the changes occurring in China, as anyone documenting events in the country would be compelled to do. However, the locus from which they present these changes is different.

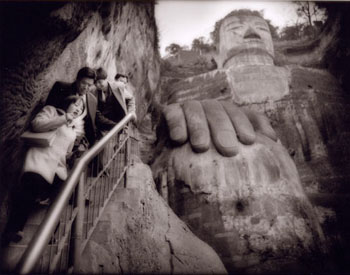

In the photography of James Whitlow Delano, we see the changes occurring in China through the institutions and constructions of the state, and the ensuing human interaction with these new public constructions. A modest woman who stands in front of a traditional building, her home, which is scheduled to be demolished, while a new skyscraper looms in the background. Commuters crowding in to get a view of a new computer installed at a bus station. Despite skyscrapers and computers, the ancient China is seen in every one of James' photos, whether with nostalgia, ambivalence or reverence. We see a picture of the Great Wall or a bamboo bridge; perhaps they remind us with irony of the construction boom that has brought about the skyscrapers and the Three Gorges Dam. Sometimes that ancient China has been turned into a tourist attraction but it is there. And in James' photos this older, more traditional China is nagging constantly at the present, silently and calmly questioning it. Delano's photos use the past to critique the present and future while Leong's photos look ceaselessly towards the future. It is almost as if they are photographing different times. Mark photographs a young heroin addict or a man who has lost both arms in a factory punch press accident. James, on the other hand, will photograph a young Dong girl with a thermos at the rice harvest or a Naxi flutist beneath a statue of Mao. While Mark may photograph an advertisement for some new and strange gizmo, James will show us a blind fortuneteller. Mark shows us the CEO of China Netcom at his desk surrounded by modern contraptions and wires and James shows us someone selling sugar cane in the midst of western-looking mannequins. In both photographers' work the tension between past and present is there but the viewpoint is entirely different. Leong's subjects seem eager to escape the old world while Delano's seem to encounter the new world perplexed and disoriented. Both of them address tourism, an industry that is growing in China with the emergence of a middle class. Leong tends to address the absurd in the tourist industry. In one of his images we see a man at a desk, set up on steps in the middle of nowhere, no roof above his head, no walls around him and not another person in sight. The picture makes no sense; it looks as if it has been set up as an elaborate joke. But, as it turns out the man is conducting legitimate business; he is waiting to take souvenir photos of tourists hiking up Huangshan Mountain. For Delano tourism is another way to highlight the tension between the old and the new, to create a dissonance that intrigues and questions. In one of James' images we see a Chinese family descending a staircase; the mother is laughing, the daughter is peering over the rail into the precipice. They strike us as strangely Western. But behind them looms a giant statue of the Buddha, a piece of history that is now a tourist destination. The sight of this modern Chinese family, visiting a Buddha statue on a vacation as opposed to at the temple for a religious reason, creates a mild cognitive dissonance for Western eyes. Something seems a bit incorrect. Through images that cause such dissonance and highlight the absurd, Delano and Leong give us a unique opportunity to reflect upon the meaning of the changes occurring in China. Migrant workers are another compelling and troubling story in China. Delano gives us a mournful image of a migrant woman outside the Beijing train station. She is on the sidewalk, her face unseen because she is crouched over, hugging her child. She is surrounded by other poor people. They all seem to be huddling against the consequences and circumstances of China's emerging market economy, less prepared than urban dwellers to adjust to the new realities it has created, yet forced to confront some of the bleaker urban realities in a search for viable income. It is another instance of the past questioning the future - we don't see any of the accoutrements of modernity in the picture; we know she is from the country and, like many of Delano's subjects, she seems out of place. Leong shows us a whole mass of migrants asleep on the floor of the train station - they have become nomadic, travelling from city to city looking for work. However, they don't look as troubled as Delano's woman with child. Leong's migrants in the train station look peacefully asleep; they seem much more in their element than the woman. China consumes more cigarettes than any other country in the world. Perhaps in the difference of the photographer's portrayal of smoking lies one of the most significant distinctions between their two styles. In Mark's case we see a 10-year-old runaway boy greedily inhaling a cigarette and staring directly at the camera. We see all the hunger of the young generation in the exaggerated form of addiction, the agency of the individual as the driving and creative, if uncontrollable, force in a changing China. In James' case we see only a cigarette, a hand and the lower half of another individual. No faces. It is not human agency that is conveyed or questioned in this picture - it is the institution of smoking. In Delano's photos it is the institutions of the state, the things that humans make which shape the reality of modern China, not necessarily the human beings themselves. In Delano's images the individuals are moving among what they've made, things bigger than themselves -- the Three Gorges Dam, a giant skyscraper, a market economy, the tobacco industry - and it is the effect of these things on the individual experience that Delano highlights. But comparisons are dubious measures of artistic works. Despite differences in technique and style there are many similarities between these two photographers. One will find much realism in Delano's romance and plenty of romance in Leong's realism. And whether absurd or dissonant, whether it is the past looking to the future or the future running from the past, both photographers create compelling portraits of the region and the historical moment. Both China Obscura and Empire: Impressions from China provide telling images of one of the world's most rapidly changing countries from two singular talents.

© Marcel Saba

|

||||||

Back to January 2005 Contents

|

|