|

→ October 2005 Contents → Feature

|

Steve Liss' No Place for Children: Voices from Juvenile Detention

|

|

||||||

|

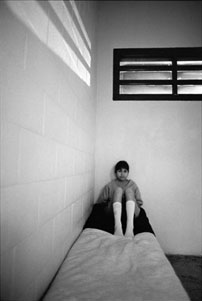

A scared young Hispanic boy cowers in a cellblock, wearing ill-fitting pants that drag on the floor. An 11-year-old boy standing on a milk crate is fingerprinted by a police officer. A 14-year-old girl lies on a bed holding a note that reads, "I hate myself. I feel I could die. I'm so stupit [sic]. I feel lonely." Charged with shoplifting, possession of marijuana, and violent outbursts, these adolescents were placed in the Webb County Juvenile Detention Center in Laredo, Texas. They are a few of the subjects captured in photographs by Steve Liss and published recently in his book entitled No Place for Children: Voices from Juvenile Detention.

Steve Liss has worked as an award-winning photojournalist for more than 30 years. On contract for Time magazine for the past 21 years, he has covered politics and presidential campaigns. Forty-one of his photographs have appeared on the cover of Time. In the early 1990s, he gravitated toward in-depth stories about social issues, which are now his specialty and give him the deepest satisfaction.

In 1998 Time sent Liss to cover George W. Bush, then governor of Texas, on a re-election campaign trip throughout the state. One of the stops was in Marlin, at the Texas Youth Commission, to demonstrate the administration's "get tough on crime" policy. The press lined up in the facility's gymnasium to watch 13- and 14-year-old children dressed in their prison clothes perform boot camp maneuvers. Following this, the press was ushered into a cellblock where a group of young offenders were seated at a metal table. While the press stood by listening to every word, Bush proceeded to address them with statements such as, "I hope you've learned your lesson." Liss was shocked and outraged at the exploitation of these minors for a political photo opportunity.

Liss had not been aware that children of such a young age were being incarcerated in the United States. After doing some research he learned that when George W. Bush was elected governor, the Texas Juvenile Justice code was rewritten to promote the "concept of punishment for criminal acts." Behavior problems were criminalized and mandatory punishments were instated. At the same time, funding was diminishing for the rehabilitation of children following their terms in detention. They are returned to the same miserable conditions from which they've come. Having observed this injustice firsthand, Liss vowed to investigate the juvenile detention system through a long-term photographic documentary project some day.

Liss' photographs have put a human face on juvenile crime rate statistics. While the arrest rate for violent juvenile defenses has declined by a third since 1993, the number of children incarcerated for lesser crimes has increased. Seventy-five percent of the children detained in the U.S. are being held for non-violent offenses, such as skipping class too much, shoplifting, running away from home or spray-painting graffiti on a wall. Many are substance abusers. Of those placed in detention centers, 50 to 75 percent have some form of diagnosable mental illness. But the detention centers do not address these needs. The children receive minimal assistance and the results of being incarcerated are devastating. Those charged with minor offenses are placed with those who have committed murder. The premise is to scare the offenders, but it backfires.

To carry out this project, Liss took a two-year leave from Time. In addition to his own resources, he sought and received support from Bill and Alice Wright, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and others. His book was published earlier this year by the University of Texas Press. Following its publication, a three-page story about the project was published in the Laredo Times and the reaction was very positive. An exhibit of the work is on display at the Laredo Center for the Arts for the next year.

Liss feels a responsibility to demonstrate that the work is relevant beyond Laredo and the state of Texas. He would like to expand the project considerably and for these photographs to be exhibited in town halls and libraries throughout the U.S. His work on No Place for Children was recognized with a Soros Criminal Justice Journalism Fellowship last year.

The project and book have been successful in shining light on a social problem which can no longer be ignored. Through Liss' photographs, our attention is drawn to the vulnerability of the children held in detention and the lack of resources to assist them. He has given his subjects a place at the table to tell their story, opening the door to understanding. Liss said in his interview, "When someone has a story to tell, particularly a young person, they're with you all the way. If you really care and you're willing to let them tell their stories, they'll open their lives to you. And that's a real gift, a responsibility that I take very seriously."

Liss advises fellow photojournalists that carrying out a documentary project is an act of faith and not to give up. "No one can be certain how effective it will be, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be done. They take time, resources, and commitment."

© Alison Beck

|

|||||||

Back to October 2005 Contents

|

|