|

| |||||||||||||

Mara Salvatrucha

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Flaco didn't look like a killer. In his early-'40s, he was tall and thin and spoke softly. One wouldn't readily think of him as a hard-core gang member who called the shots inside a notorious Salvadoran prison.

A Los Angeles homeboy, he was deported from the U.S. and now is serving 25 years in Ciudad Barrios Penitentiary for a murder he says he didn't commit. An aging and overcrowded facility, Ciudad Barrios is solely devoted to some 900 incarcerated members of MS-13.

I felt uneasy trusting him, but had no other choice. I wanted to see the prison up close and I followed him inside.

I was in El Salvador with a pair of Los Angeles Times reporters to document the role of U.S. deportation policies in spreading MS-13, which traces its roots to the immigrant neighborhoods west of downtown L.A.

In the 1980s, a million Salvadoran refugees fleeing civil war arrived in the U.S., many ending up in Los Angeles. The exodus included dispossessed teens who formed MS-13 in some of the city's most gang-infested areas.

An unintended consequence of deportation has been the rapid growth of MS-13 in Central America. Today, close to 1,800 MS-13 members are imprisoned in El Salvador, more than all other gangs combined.

Ciudad Barrios is "like a college for MS-13," says one top law enforcement official.

And there we were, trailing Flaco into the belly of the beast. An assistant director from the corrections ministry had briefed us before we entered. Stabbings are common, he said, and he could not guarantee our safety.

"If you sense any trouble, get out as quickly as you can," he said. It sounded to me a lot like a release of liability. And as we went in, he told us he wasn't coming along.

I heard a heavy iron gate slam shut behind us as we descended to an exercise yard lined with scores of gang members. I looked behind me and saw that the guards had decided not to come in either. We were on our own.

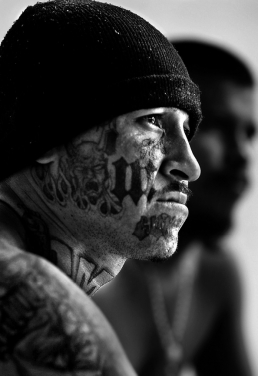

Oddly, the prison smelled of laundry detergent as freshly washed clothes hung from lines strung between cellblocks or laid flat to dry on sun-baked courtyards. Music blared from a radio as we walked the gauntlet crowding the hallways, all the while enduring looks of anger and intimidation, a behavior known to gang members as "mad-dogging." Most of the inmates wore only shorts and tennis shoes, and many sported lots of tattoos. It was hot and dirty and my discomfort was compounded because all eyes were on me and my colleagues.

Some inmates had completely tattooed their faces with the markings and symbols of MS-13, giving them a palpable aura of evil. A few asked who we were and what we wanted. Many became agitated, protesting loudly when I raised my camera. But a quick glance from Flaco quieted them down, and I began to gain confidence about taking pictures. Still, it felt like they barely tolerated me and I shot without lingering long.

I made it a point to shake hands with everybody I met. Meant as a gesture of respect, the action seemed to disarm some.

Passing through a series of gates we visited a woodworking shop, where thick clouds of sawdust hung in the air. In one corner three inmates cooked a pot of beans over an open fire, and I feared the flames might ignite the sawdust.

In the woodshop, inmates made a variety of home furnishings, most of which featured the MS-13 logo. The items sold outside the walls help supplement the prisoners' meager food rations.

It was all a bad scene, really, a kind of microcosm of L.A.'s worst nightmare transplanted. Claustrophobic, crowded tiers led to darkened, bed-less holding cells and fetid latrines overflowing with human waste. The Salvadoran government clearly has its hands full with simply housing prisoners, never mind rehabilitation. For most of the 900 inmates the MS-13 family still is all there is.

Officials say that dozens of hits on rival gang members have been ordered from the prison. And beyond its walls MS-13 keeps drawing recruits from a large pool of disaffected youths raised in abject poverty. The gang's violent subculture simply evolves in boilerplates like Ciudad Barrios.

After more than four hours, we'd run out our string. We saw virtually every corner of the prison and it was time to leave. We made our way back to the gate where we came in and were greeted by a pair of smiling guards. They seemed genuinely glad to see us.

As we walked out my whole body seemed to exhale. It was as if I'd been holding my breath forever and I was exhausted from all the tension.

I thought to myself that nothing good could ever come from a place like this. And it felt great to emerge from the depths of hell.

© Luis Sinco

Dispatches are brought to you by Canon. Send Canon a message of thanks. |

|||||||||||||

Back to February 2006 Contents

|

|