|

→ March 2006 Contents → Column

|

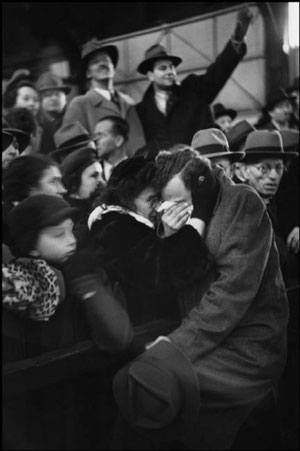

Henri Cartier-Bresson:

The Impassioned Eye March 2006 |

|

|||||||||

|

"Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Impassioned Eye" is not a documentary in any of the many accepted forms we know. It is not the documentary I would have made had I the same material at my disposal. This aside, as short a film as this is — it runs 72 minutes — and lacking the context it deserves and should have had about the man and his life, it gives us a fascinating insight into one of the greatest photographers who ever lived.

He rarely photographed the obvious, preferring to make his way where his instinct told him to go and then, simply — not quite the right word — take the picture destiny laid out for him. In some cases he needed only one shot, in other cases, just a few. And, perhaps, that was his genius. As some critics indicated, in the film we enter a master class in photography. To that I have no objection. I found what Cartier-Bresson said useful and insightful, and disarming as well as charming.

The film is mostly an extended interview in a number of different settings conducted by director Heinz Butler — rare for Cartier-Bresson, considering he was a private man in a very public profession. Music surrounds many of his comments. Sometimes we even pause long enough to meditate with Cartier-Bresson as we listen with him to the classical piano in the background. Despite the director's static approach, it is triumph enough to hear Cartier-Bresson talk about only a handful of the pictures from his cannon. His memory of the places he had visited and the people he had met was clear and often infused with good humor. Considering how rare it was for him to allow the public an opportunity to understand his work as a photojournalist, to see him recall how he took those pictures was worth the price of the ticket.

Director Heinz Butler includes interviews with Arthur Miller, actor Isabelle Huppert, Cartier-Bresson's publisher Robert Delpire and photographers Elliot Erwitt, Josef Koudelka and Fernando Scianna. All try to help us understand a great photographer who had been mostly reclusive and who said very little in public through much of his life.

Most of the photos we see were taken with his 35mm Leica between the 1930s and 1960s. We see some of these photos as they appear in books, or when Cartier-Bresson holds a print before the camera and discusses its origin. We see a marvelous, thoughtful picture of Marilyn Monroe. We share the deadpan look on Marie and Pierre Curie as he enters their apartment and takes an inspirational photo of them. We see Henri Matisse framed in the doorway of his farmhouse. We share with him his remarkable ability to create geometry and architecture where none might have been apparent until he squeezed the trigger of his camera. We see a man leaping over a puddle and I wonder how in the world he made that shot because I know it would be impossible ever to duplicate it.

In the 1970s, he put his camera away and took up drawing. As he grew older, he decided he would rather put pencil to paper than continue to put his eye to the camera. Had he seen enough or too much of the world? I suppose he might have grown weary of travel, of packing and unpacking his camera and luggage. But he had seen so much and photographed more than most, that perhaps he woke one morning satisfied with his life and work. It almost makes no difference because his legacy is monumental.

Had I made the film with the same material I would have added more background to get an understanding of Henri Cartier-Bresson's life, his loves, his adventures, his failures, and how success changed him or not. We get little of this in the film, but what we do get is priceless, and we should be grateful for even this small look at how he worked, which is now permanently on the record.

© Ron Steinman

|

||||||||||

Back to March 2006 Contents

|

|