|

→ July 2006 Contents → Column

|

REMEMBERING SLIM & ARNOLD

July 2006 |

|||||||

|

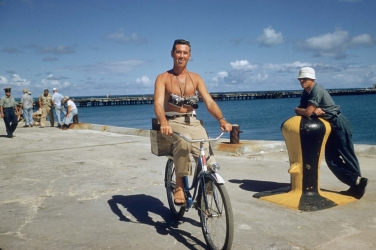

May 29, Memorial Day â Photographer George "Slim" Aarons reclined in a wheelchair in a V.A. hospital in Montrose, N.Y. Recently slowed by a stroke, his eyesight failing, and only able to communicate by squeezing friends' or relatives' hands, Aarons seemed engaged nonetheless. At a ceremony honoring vets who had lost their lives in service to their country, he sat front and center among other hospital residents, tapping his foot to the beat of a marching band.

Slim Aarons enjoyed his last Memorial Day, then died in his sleep some 20 hours later, at age 89.

Two other journalists, it so happens, would also pass on during the same time frame. On Memorial Day, CBS cameraman Paul Douglas, 48, and soundman James Brolan, 42, covering the war in Baghdad, died when a bomb exploded near their Humvee; CBS correspondent Kimberly Dozier was severely injured in the blast. With the death of these two newsmen, a woeful Rubicon was crossed. On that day, the number of working journalists killed in Iraqâ according to Reporters Without Bordersâ became equivalent to the number of all accredited newsmen who died during two decades of combat in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. (That figure of 71 journalists killed in Southeast Asiaâa number that is slightly higher than past estimatesâwas computed last summer, says Richard Pyle, former Saigon bureau chief of The Associated Press, when veteran correspondents and photographers made a consensus tally during a gathering in Vietnam for the 30th anniversary of the fall of Saigon.)

What was it, then, that distinguished the wars that Aarons and Pyle covered from that of Douglas and Brolan? What was it, beyond the pressures of the 24/7 news cycle, beyond the myriad and new restrictions placed on press coverage, beyond the heightened dangers of documenting conflict in the 21st century? "America doesn't seem to care now," insists photographer David Douglas Duncan, among Aarons' best friends and colleagues. Duncan, 90, is one of the rare photographers, living or dead, to have taken classic photographs in World War II and Korea and Vietnam. "America's too comfortable to bother with this war. Most days in [New York], and in most towns in America, we're insulated. There's no sense that a war is going on, even if we turn on the TV. There's no sense of sacrifice today, on anyone's part, despite the gas prices, which are a joke."

"Look around," says Duncan, surveying the lobby bar of a Manhattan hotel. "There's not a single person in uniform. When I came here for Gordon Parks' funeral in March, the only people I saw in uniform were flying the plane."

Duncan's friend Slim Aarons surely would have shared his dismay.

June 8â Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch addressed the congregation.

"Goodbye, dear Arnold," said Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch, his eulogy drawing to a close. "May you find joy and happiness as you gather with your kin and dwell in the celestial retinue. May you discover all of the great truths of the universe that are hidden from us during our mortal days."

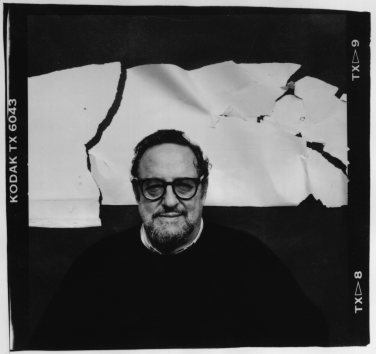

Arnold. Arnold Newman. Hebrew name: Abraham.

At the time, Arnold Newman was a young American photographer living in Palm Beach, Fla., his family's fortunes having been buffeted about by the Depression. Newman had become disenchanted as a professional shooter in the South. And so, to brighten his prospects, he decided to come to New York, where he fell in with some of the photographers, painters, and sculptors who had been forced to flee Europe.

He observed and absorbed. For several years he had been taken with the work of the intrepid photojournalists of the government-sponsored Farm Security Administrationâmen and women who had traveled the heartland and visually documented the Depression's impact on the American soul. He studied and later befriended pioneers in music, literature, and architecture, along with modern artists such as Mondrian, Chagall, and Max Ernst, many of whom gave him paintings, drawings, or lithographs, inevitably signed, "To my friend Arnoldâ¦."

In 1942, uncertain as to whether he could earn a real living behind a camera, he was encouraged by a friend to pay a visit to Beaumont Newhall, then the curator of photography at New York's then-fledgling Museum of Modern Art. Newman was all of 23; the new museum was all of 13. Newhall was so enamored of the young photographer's vision, he introduced him that very day to photographer-artist-curator Alfred Stieglitz, who was equally impressed. Within 48 hours Newman was promised his own exhibitionâ a two-man show with his friend Ben Roseâ at the influential A.D. Gallery. "Those two days changed my life," Newman would often recount, still astounded decades later by his early good fortune.

That exhibition and subsequent exposure led to Newman's recognition and acceptance into the booming New York photo community. In a few years, lucrative magazine assignments would come his way from Life, Harper's Bazaar, and Holiday. And he soon found himself using the photographic frame to combine his passion for documentary photography with his predilection for the unconventional but harmonious composition he had revered in the work of many of his modernist contemporaries. In the process, Newman forged a new photographic genre: the environmental portrait, of which he would become the 20th-century godfather.

(CLICK TO READ "WHEN ARNOLD MET ARAFAT" by David Friend, first posted on The Digital Journalist on December 2003)

On June 6, 2006, 54 years after that prescient photo show, Arnold Newman, a colossus of American photography, passed away at age 88.

Three nights before his death, we spoke by phone as he rested at a facility operated by Mt. Sinai Hospital. We talked about his recent stroke, about the death of Slim Aarons, about Arnold's desire to rebound soon in order to better care for his wife, Gus, who had medical issues of her own. "How can I do that from here?" he said, rather anxiously.

He mentioned that he hoped to photograph George W. Bush soon. (He had wrangled portrait sessions with every U.S. president from Harry Truman to Bill Clinton.) And, as he often did, he briefly discussed plans for yet another book, this one a memoir. "I want to get out of here soon and start working," he remarked, with a tone of annoyance and urgency.

At his funeral, on June 8, Rabbi Hirsch of Manhattan's Stephen Wise Free Synagogue would say to assembled relatives, friends, and colleagues: "Arnold's Hebrew name was Avraham -- Abraham. His biblical namesake was also a pathfinder. He was the first Jew. He was the first to see the world in a different way. After Abraham the world would never again be as it was beforeâ. And God said [of Abraham]: 'See, I have singled him out; I have filled him with the spirit of God and planted within him special understanding, knowledge and skill. I have poured inspiration into his heart..."

"This was our Arnold. Take him Eternal God. 'He was a man all in all. We shall not look upon his likes again.'"

© David Friend

|

|||||||

Back to July 2006 Contents

|

|