The first thing you noticed about her was how small she was and how frail she looked. The second thing you noticed was that she was never still. The force of nervous energy that propelled her through the battlefields of Vietnam did not release her upon her return.

|

French-born photojournalist Catherine Leroy, at age 22, is seen in this 1967 file photo during Operation Junction City in Vietnam near the Cambodian border. Leroy, whose stark images helped tell the story of the Vietnam War in the pages of LIFE magazine and other publications, died on July, 8, 2006. She was 60. (AP Photo) |

I had never met Catherine Leroy before doing the interviews for my book

Shooting Under Fire in 2002. I had heard the legends, of course; how she arrived in Vietnam in 1966 with one Leica, no experience and even less money; how she parachuted with the 173rd Airborne in a combat operation; how she lived like a Marine and swore like one too; how she was wounded, only a shattered camera around her neck saving her life. Of course I knew the photographs she had taken, the anguished picture of a Navy Corpsman unable to save the life of his Marine buddy, the first photographs of the North Vietnamese Army in action, and many others, not only from Southeast Asia but from Lebanon and Northern Ireland as well. It wasn't until I opened the front door of my New York apartment that I let in this whirlwind that blew in and out of my life until the end of hers.

She paced around the small apartment, complimenting me on the view of the East River as if I had produced it myself, interrupting our conversation at regular intervals to take a cigarette break on the balcony after I had established that it would not be permitted inside. That was the other thing you quickly noticed about Catherine – the extent of the addiction to nicotine that would eventually end her life. Interviewing her was often tiring, but always rewarding. The stories she told were moving, funny, outrageous and often suspiciously embellished, Did she, for instance, really live in a brothel in Saigon without realizing the nature of the establishment? It's unlikely, even for the naïve French girl that she claimed to be at the time. She was born in Paris, after all. But in her heavily accented English she managed to put into words feelings that many of the other war photographers only hinted at or skirted around.

|

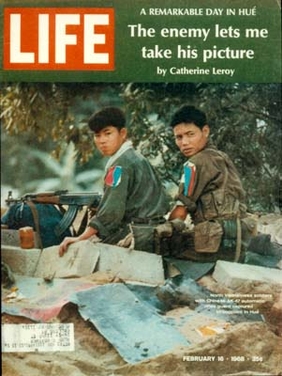

Cover of LIFE magazine featuring photographer Catherine Leroy's greatest "scoop." Her one-day capture by the North Vietnamese Army while covering the battle of Hue in 1968 produced a rare glimpse of the enemy. Catherine Leroy / LIFE |

She wasn't the greatest photographer of that war, no female Don McCullin, Larry Burrows or Philip Jones Griffiths. Her technical ability was often shaky, and her composition less than perfect, but despite this, or maybe because of it, her pictures had a direct and primal appeal in the way that song heard across a bar can often be more moving than the most polished studio recording. One of the reasons that her work had such impact was her sympathy for the soldiers whom she photographed, a sympathy that bordered on love. This was at a time when "Support Our Troops" was not emblazoned on every third automobile, and her attitude led her to disillusionment with her friends in Paris, and a feeling of isolation from the civilian world. In many ways she was like her sister photographer Dickie Chappelle, who was killed in Vietnam and who so loved and was beloved by the Marines that they erected a memorial to her. Leroy had similar feelings for the GIs. She said in the interview, "There was a bond that had been established with them, and anybody who spoke out against the war in Vietnam was also speaking out against those who were fighting the war, and those who were fighting the war were my friends. Yes, I was opposed to the war, but not at all in the same way, because of the friendship, and the strength of bonds that often were established in minutes. Friendship; camaraderie; generosity; all of this is what you have in time of war. People reveal themselves without their masks. The GIs were like my brothers. We were the same age, and of course, I loved them." She ended this part of our conversation with, "Besides I cannot photograph anybody for whom I don't have any feelings. I would rather stay under my dome and smoke a cigarette and drink a good glass of wine."

Her pictures reflect this affection, for they are rarely heroic. These are not portraits of a warrior class but of ordinary, frightened and often bewildered young men trying desperately to stay alive, and relying upon each other to pull off this seemingly impossible feat. In fact the nearest that she gets to portraying warriors is in the remarkable photographs that she took of the North Vietnamese Army when they captured her and a French writer during the battle of Hue. They were released after a few hours because they managed to persuade an officer that they were working for a Parisian magazine that had commissioned them to do a story about the victorious NVA capturing the city. This is the one time when the photographs have an impersonal feel to them, which I am sure is more to do with the fact that she spent so little time with the North Vietnamese troops rather than any inherent quality they had. In fact she said of the experience of meeting the young officer, "It was a shock for me to see him because since I had been in Vietnam the only North Vietnamese I had seen were wounded, dying, or dead." It was to be her greatest scoop, making the cover of LIFE along with a major feature.

|

Weary U.S. Marines take a break during the battle of Hue, Vietnam, February 1968. Catherine Leroy |

She had grown up looking at

Paris Match, ("I practically learned how to read through

Paris Match.") and was fascinated by the photographs and the world that they opened up for her. She also remembered her father crying as he listened to the radio reports of the fall of Dien Bien Phu, the last battle of colonial France, and the effect that his tears had on her. When she was old enough she took her Leica and her courage and went to Saigon. There she met Horst Faas in the Associated Press office. "I was a child, completely wide-eyed, and I said to him: 'What do I need to photograph?' He opened the drawer, and inside there was a pile of wire photographs. I looked at this stack of pictures, and I knew immediately what I had to do. I got my accreditation, and I went."

And she didn't go quietly. She wasn't one of those photographers whose presence went unnoticed and unremarked. In fact, my theory is that the reason the NVA released her and the writer so quickly had nothing to do with them buying the French magazine story, but because letting her go was a lot easier than keeping her. Because of her diminutive stature she was unable to carry enough provisions for herself into battle, so she came up with a particularly Leroy-esque solution. She found a place in Saigon that sold Beaujolais wine in cans, a six-pack of which she would take with her in her poncho. She would share this with the unit she accompanied in exchange for food. She was, by many accounts, one of the more popular photographers with the troops.

She was acutely aware of the emotional effects that combat has upon those who experience it. She described it in this way:

"I was so scared sometimes, so scared; I really never thought I was going to get out of this alive. But when it was all over, and when I was alive and unhurt, like the time when I had a bullet in my canteen, the release of fear gives you a rush, a high of just being alive; you are alive like you've never felt alive before. It's not something that's pleasurable in a sensual sense. It's pleasurable in the sense of sheer animal survival. It's your primary brain, your reptilian brain; you are alive as an animal is alive. It's very low and very primal."

I don't think anyone has ever put it better.

For many photographers who covered it, the Vietnam War was the defining period of their lives, a reference point to which they constantly returned. She was to do many fine photographs from many other conflicts, producing the moving book God Cried out of her time in Lebanon, and a documentary film about the anti-war activist Ron Kovic called Operation Last Patrol. But the effect that Vietnam had upon her, and so many others, was profound. Everyone pays some price for being under that amount of stress so constantly and for so long. She described hers: "When I left Vietnam I was 23, and I was extremely shell-shocked. It took years to get my head back together, because I was filled with the sound of death, and the smell of death." It alienated her from mainstream life in the same way that most combat veterans are isolated in some form or another. She told me the story of her arrival back in the town of her birth.

|

French-born photojournalist Catherine Leroy, at age 22, is seen in this 1967 file photo in Vietnam before a combat jump for Operation Junction City. Leroy, whose stark images of battle helped tell the story of the Vietnam War in the pages of LIFE magazine and other publications, died on July, 8, 2006. She was 60. (AP Photo) |

"When I returned to Paris I couldn't cross the street without being almost run over by a car; I couldn't sleep at night; I couldn't function in a normal manner. I couldn't express myself with my friends and they couldn't understand me. They were very much opposed to the war, and they accused me of being pro-American. They were all leftist intellectuals and the leftist intellectuals of the Left Bank in Paris never go anywhere but the Left Bank in Paris, and so I didn't have anything to say to them any more. I remember there was a lunch that was given in my honor upon my return, and they all started to have this big political discourse and I felt that I was being attacked. I was in such a fragile mental state that I started to cry, stood up, and left. I took it very personally."

The last years of her life were difficult ones. She would call me up and say in that musical accent of hers, "Bonjour, Pee-tare. I'm broke; I'm so fucking broke." She had a fashion business called Piece Unique that never quite worked out for her, and she produced a fine Web site that sold prints from some of the best photographers who covered Vietnam (http://www.pieceuniquegallery.com/). She was surprised by how limited a market there was for framed images of the horrors of war. She also published a book of the work that was on the Web site, called Under Fire. I told her I forgave her for stealing half my title, which she said was coincidental! I wondered, when I heard of her death, whether, as she lay dying, she had reconsidered something she also said in the interview: "I've never been scared to die. I love life too much, and I want to live it as fully as possible, but I'm not scared to die at all. I'm scared of being old and sick, yes, but not to die." If you go to her Web site today and click on the 'What's New' button the page that you bring up declares: News. Coming Soon! Unfortunately the news is that there will be no news, not of this small, complex person who was larger than life, and whose legacy is the memory of the faces of the boys we send to war, a memory that we too soon and too often forget.